Friday

By the end of last year, my tennis game—a passion second only to reading—had reached a new level of excellence. Then, however, I developed a case of plantar fasciitis, and that was followed by cataract surgery in my left eye. When I finally returned to the courts two months ago, it was as though I was playing the game for the first time. My eyes refused to coordinate and balls bounced off my racket frame when I tried to serve. I ran gingerly and couldn’t reach balls that had once been routine.

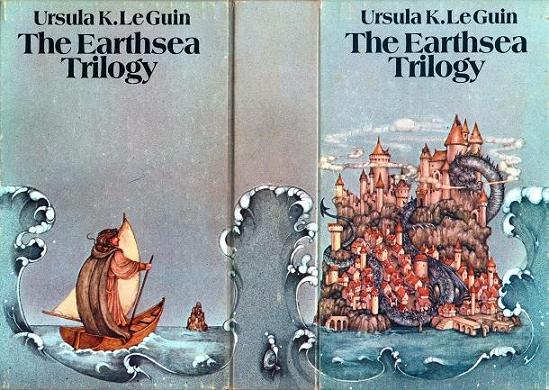

Luckily I had literary precedents to comfort me, episodes in Lloyd Alexander’s Black Cauldron and Ursula LeGuin’s Wizard of Earthsea in which the protagonists lose their powers. That’s one thing that a lifetime of reading gives you: whatever happens, you can find a narrative where something similar has happened.

In Black Cauldron, Taran inherits “the brooch of Adaon,” a magical talisman that enhances his senses and awareness and gives him special prophetic powers. Wearing it, he feels a sense of mastery:

As Melynlas cantered over the frosty ground, Taran caught sight of a glittering, dew-covered web on a hawthorn branch and of the spider busily repairing it. Taran was aware, strangely, of vast activities along the forest trail. Squirrels prepared their winter hoard; ants labored in their earthen castles. He could see them clearly, not so much with his eyes but in a way he had never known before.

The air itself bore special scents. There was a ripple, sharp and clear, like cold wine. Taran knew, without stopping to think, that a north wind had just begun to rise.

Taran describes the experience thus:

“All I know is that I feel differently somehow. I can see things I never saw before—or smell or taste them. I can’t say exactly what it is. It’s strange, and awesome in a way. And very beautiful sometimes. There are things that I know…” Taran shook his head. “And I don’t even know how I know them.”

With these powers, he is able to guide his friends through treacherous marches and save them from the Death Lord’s murderous followers. He must surrender it to acquire the black cauldron, however, and finds himself stumbling through a reality that once he negotiated easily. That’s how I felt out on the tennis courts.

In Wizard of Earthsea, Ged is the most talented student at the magicians college, effortlessly performing feats of magic that others must labor to learn.

At all these studies Ged was apt and within a month was bettering lads who had been a year at Roke before him. Especially the tricks of illusion came to him so easily that it seemed he had been born knowing them and needed only to reminded.

I cite the passage, not because I’ve ever been a gifted tennis player, but to capture the distance between before and after. Ged loses his powers after his magic opens up a forbidden doorway and he is nearly killed by a dark shadowy figure. When he recovers, he discovers that he has lost his instinctive feel and must learn magic the hard way, just as everyone else does:

The boys he had led and lorded over were all ahead of him now, because of the months he had lost, and that spring and summer he studied with lads younger than himself. Nor did he shine among them, for the words of any spell, even the simplest illusion-charm, came halting from his tongue, and his hands faltered at their craft.

What I am describing is the experience of all injured athletes, and some never fully regain their abilities. Seeing these powers through the lens of fantasy fiction captures how precious their skills appear and how tragic it is when they are lost forever. To borrow a line from Robert Frost’s “Oven Bird,” we must grapple with what to make of a diminished thing.

Yesterday I hit some of my first good ground strokes in months, and my foot wasn’t too sore afterwards. Taran and Ged also recover. Hope springs eternal.