Tuesday

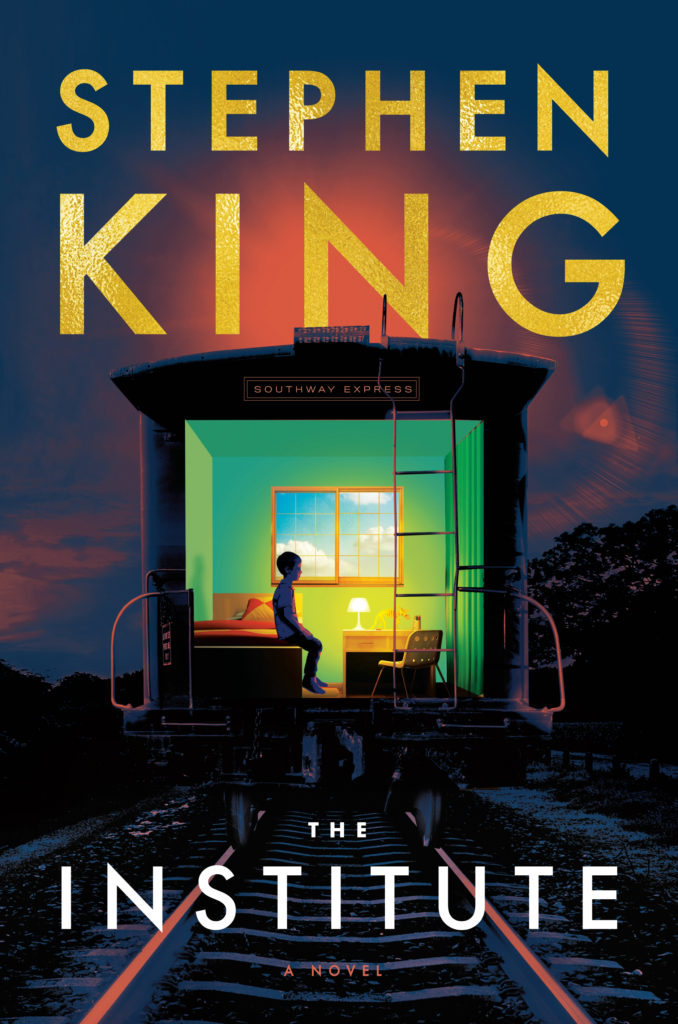

Literary Hub alerted me to this New York Times interview with Stephen King that gets at the sometimes tangled relationship between fiction and current events. The Institute features kids with supernatural talents who are rounded up and placed in detention centers by a shadowy organization. After they have been used up, they are brutally discarded.

Of course, America has also been rounding up children and placing them in cages. Anthony Breznican notes that, while King was writing his novel last summer, its broad strokes

began to parallel what was happening in real life: Children, seeking asylum at the border, were being removed from their parents under the administration’s family separation policy.

King acknowledges the parallels but says they weren’t conscious. Rather, given that he is writing in the age of Trump, certain themes arise naturally:

“All I can say is that I wrote it in the Trump era. I’ve felt more and more a sense that people who are weak, and people who are disenfranchised and people who aren’t the standard, white American, are being marginalized,” King says. “And at some point in the course of working on the book, Trump actually started to lock kids up.” At least seven children have died while in immigration custody since the policy was enacted. “That was creepy to me because it was really like what I was writing about,” King says. “But I don’t want you to say that was in my mind when I wrote the book, because I’m not a person who wants to write allegory like Animal Farm or 1984.

The interviewer confirms that King confines his political opinions to social media (he has 5.4 million twitter followers) and regards novels as “a place to explore human nature, not current events.” But King also points out that “if you tell the truth about the way people behave, sometimes you find out that life really does imitate art,” and adds, “I think in this case it really has.”

As I see it, authors are more like shamans than journalists, capturing the dream-like contours of our lives so that we have something tangible to reflect upon and explore. One can say of King what Harold Bloom says of Edgar Allan Poe, that he dreams America’s nightmares. His novel IT, for instance, captures America’s endemic violence, with Pennywise the clown making regular appearances in racial firebombings, homophobic murders, child molestations, instances of marital abuse, deadly barroom brawls, and various explosive bloodlettings. The Institute sounds as though it captures what American adults are doing to the next generation.

Fortunately, King doesn’t see this generation as helpless. Apparently he thinks of the novel

“not as a horror story but as a resistance tale.” One has 12-year-old telekinetic genius Luke, teenage mind reader Kalisha, and 10-year-old power-channeler Avery joining forces to rebel inside their detention center. For all his horrific descriptions of American life, King sees hope in the next generation.

I fervidly hope that King’s optimism is a case of shamanistic depth rather than sentimental wish fulfillment. Then again, I think of Neil Gaiman’s observation about fairy tales being “more than true: not because they tell us that dragons exist, but because they tell us that dragons can be beaten.”