Wednesday

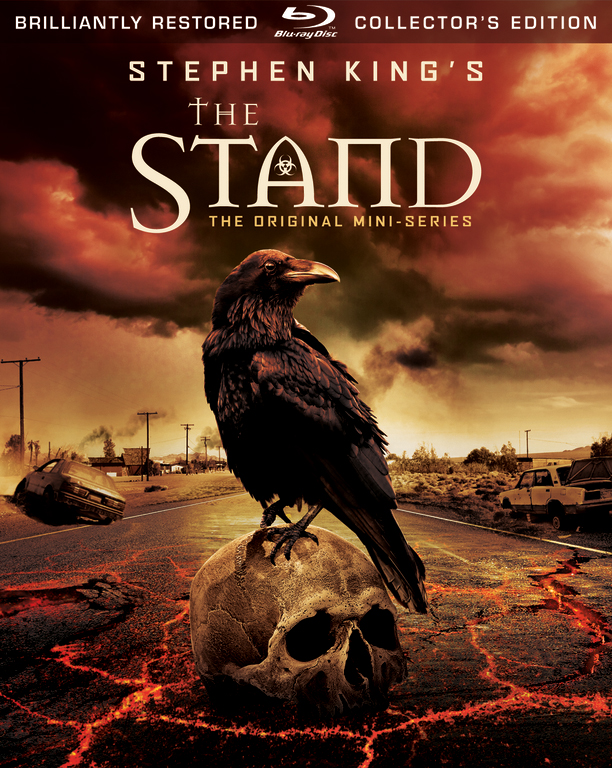

It appears that the world has a coronavirus pandemic on its hands. Although not nearly as deadly as the flu that takes out 99.9 percent of the world’s population in Stephen King’s apocalyptic novel The Stand, the coronavirus is still a killer. Thanks to Donald Trump, the United States is far less prepared to deal with it than it would have been three years ago.

In a chillingly impersonal chapter, King describes how the virus spreads. An employee at a biological weapons facility runs away following an accident, but not before he has been infected. Gas station owner Bill Hapscomb contracts the virus after investigating the car in which the man and his family have died, and he passes it along to his police officer cousin Joe Bob Brentwood. The following passage picks up the story from there:

On June 18, five hours after he had talked to his cousin Bill Hapscomb, Joe Bob Brentwood pulled down a speeder on Texas Highway 40 about twenty-five miles east of Arnette. The speeder was Harry Trent of Braintree, an insurance man. … And [Joe Bob] gave Harry Trent more than a speeding summons.

Harry, a gregarious man who liked his job, passed the sickness to more than forty people during that day and the next. … Harry Trent stopped at an East Texas cafe called Babe’s Kwik-Eat for lunch. … On his way out, a station wagon pulled in … Harry gave the New York fellow [Edward Norris] very clear directions on how to get to Highway 21. He also served him and his entire family their death warrants without even knowing it. …

That night [the Norris family] stayed in a Eustice, Oklahoma, travel court. Ed and Trish infected the clerk. The kids, Marsha, Stanley, and Hector, infected the kids they played with on the tourist court’s playground – kids bound for west Texas, Alabama, Arkansas, and Tennessee. Trish infected the two women who were washing clothes at the Laundromat two blocks away. Ed, on his way down the motel corridor to get some ice, infected a fellow he passed in the hallway. …

During their wait in [Doctor] Sweeney’s office they communicated the sickness which would soon be known across the disintegrating country as Captain Trips to more than twenty-five people, including a matronly woman [Sarah Bradford] who just came in to pay her bill before going on to pass the disease to her entire bridge club. …

She and Angela went out for a quiet drink … they managed to infect everyone in the Polliston cocktail bar, including two young men drinking beer nearby. They were on their way to California … The next day they headed west, spreading the disease as they went. …

Sarah went home to infect her husband and his five poker buddies and her teenaged daughter, Samantha. … The next day Samantha would go on to infect everybody in the swimming pool at the Polliston YWCA

In our interconnected world, viruses spread inexorably unless concerted action is taken to stop them.

As depicted in The Stand, a U.S. government biological warfare lab invents the virus that wipes out the world population. In our own reality, the Trump administration has been busy disassembling the mechanisms that President Obama set up to guard against pandemics.

Foreign Policy’s Laurie Garrett describes how, following the Ebola pandemic, the Obama administration

set up a permanent epidemic monitoring and command group inside the White House National Security Council (NSC) and another in the Department of Homeland Security (DHS)—both of which followed the scientific and public health leads of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the diplomatic advice of the State Department.

In his attempt to undo all things Obama, Trump has targeted these command groups:

In 2018, the Trump administration fired the government’s entire pandemic response chain of command, including the White House management infrastructure. In numerous phone calls and emails with key agencies across the U.S. government, the only consistent response I encountered was distressed confusion. If the United States still has a clear chain of command for pandemic response, the White House urgently needs to clarify what it is–not just for the public but for the govenrnment itself, which largely finds itself in the dark.

And that’s not all:

In the spring of 2018, the White House pushed Congress to cut funding for Obama-era disease security programs, proposing to eliminate $252 million in previously committed resources for rebuilding health systems in Ebola-ravaged Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea. Under fire from both sides of the aisle, President Donald Trump dropped the proposal to eliminate Ebola funds a month later. But other White House efforts included reducing $15 billion in national health spending and cutting the global disease-fighting operational budgets of the CDC, NSC, DHS, and HHS. And the government’s $30 million Complex Crises Fund was eliminated.

Meanwhile, the most recent recipient of the Congressional Medal of Freedom assures us that “the coronavirus is the common cold, folks.” That would be right-wing radio host Rush Limbaugh.

Stephen King provides a salutary reality check whenever we need to push through denial.