This post is coming to you from Maine, where we have arrived for the Bates family reunion that we hold every three years. Before turning to books and the special quality that reading acquires in the context of a summer vacation, however, I hope you will indulge me as I describe the Bates Family Cottage.

We call this a cottage although it looks more like a house, being two stories high and featuring a large wrap-around porch. It is located in Turner, seven miles north of Lewiston and Auburn, and is situated on top of Ricker Hill. Ricker Hill Orchards has been in the family since 1803 and is now one of the largest apple farms in the state of Maine. The Rickers (along with the Timberlakes) still run the farm.

We are linked to the Rickers through my great grandmother Sarah Ricker who (so the family legend goes) was the first woman to graduate from Bates College in Lewiston, although she wasn’t a Bates then and the Bateses were not connected with the college. Rather, she then journeyed out to Illinois to teach and met my great grandfather, Thomas Fulcher Bates, in Evanston. They built the “cottage” for their summer visits in 1903, and it has passed down through my grandparents to my father and his two brothers. Of those, only my father remains, and now the eleven members of the next generation are the official owners. We live all over the country, from Colorado to Tennessee to Iowa to Maine, and it remains to be seen whether the cottage will pass on to the 17 members of next generation.

I sometimes wonder if the cottage is what keeps us together as a full clan and whether, when it finally succumbs to the rough Maine winters, we will disintegrate into autonomous family units, with some of the cousins staying in touch and others not. From a strictly utilitarian view, the care and expense that goes into the cottage doesn’t make sense for some of the cousins as they seldom use it. Yet the old pictures on the wall, oval photographs of stern faced men and bundled up women, seem to demand that we keep the lineage going.

Among the photos is John Swett, grandfather to my great grandmother Sarah, and his brother Leonard, who rode the circuit with Abraham Lincoln (they took turns as defending and prosecuting attorneys, according Carl Sandburg’s biography of Lincoln). There is an old photograph of Lincoln, with an original signature pasted in. There are family photos of each generation, including the large photos taken every reunion where we have to stand three deep.

Along with the pictures are the memories, embedded deeply into the furniture and into the board games that we play again each summer, perhaps for ritual reasons. Some of the furniture has been here my entire life, some I associate with my grandmother’s house in Evanston. There is a long dining room table, and we still eat from the old blue willow dishes that we ate from as children, although to these have been added plastic plates. There are old dressers and wrought iron bedsteads in the bedrooms, along with white ceramic pitchers and basins from the days before the cottage had running water. This past year we finally replaced the old claw foot bathtub when we had to redo the plumbing—some of the older generation were having trouble getting in and out of it, and the shower we had Gerry rigged above it was rotting the floorboards. We engage in an elaborate dance between tradition and modern convenience and continue to draw the line at television and the internet.

And then there are the books. Some of these almost no one today has heard of, but they continue to exert power over me. There is How They Carried the Mail and A Child’s History of the World. There is a passel of Thornton Burgess animal books such as Buster Bear, Danny the Field Mouse Paddy the Beaver, and Unc Billy Possum. Before me as I write this are The Voyage of Doctor Doolittle and two books by E. Nesbitt, The Treasure Seekers and The Would-Be-Goods. I see a beat-up series of Atlantic Monthlies from 1928. Also from 1928 is Frankford Sommerville’s The Spirit of Paris, containing the following meditation of change and continuity:

“Paris is changing, but these things do not change. The brisk, champagny atmosphere which staves off fatigue—the fatigue of work or pleasure—so much longer than in the heavier atmosphere of our country [England], has not changed in spite of the experience of recent floods. And equally unchanged are the fundamental points of the French character—their love of pleasing and their love of being amused, their courtesy, their innate Bohemianism and indifference to the ostentatious side of life—to keeping up appearances.”

More recent books have made their way into the Cottage collection, including a number of mysteries and the entire Harry Potter series. Rather than seeming out of place, Rawlings’ books seem to have taken on the aura of the older books, partly because of the dust they have picked up but maybe also because the series features chaotic libraries and ancient books strewn randomly around. Randomness characterizes the Cottage collection: some of the books are to be found in rickety old handmade bookshelves, others are housed behind glass. Holy hell would be raised if someone went through them to cull them.

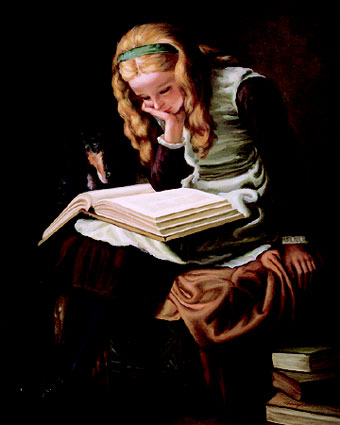

Reading in the cottage does not feel to me like reading elsewhere. For one thing, one doesn’t have to justify to oneself what one is reading. One chooses one’s book through whimsy and reads without an agenda, even the agenda of improving oneself. Often I reread children’s books, stepping out of time to go back in time. I sometimes dip into the Peter Whimsy mysteries (we have the entire series), which seems appropriate given the deep strain of English reserve that runs in my family.

Anthropologist Mircea Eliade talks about the difference between sacred space and profane space, and vacation space seems akin to the former, a place out of time in which one communes with mystery. Books themselves are a form of sacred space, and when one reads books on vacation, one seems to connect up with playfulness distilled to its essence. Whatever I read—the particular book doesn’t seem to matter—I feel restored.

One Trackback

[…] insulation to warrant winter visits. It is a beautiful, quirky old house that my father-in-law describes better than I ever could, though my associations are obviously somewhat different than his. It’s a […]