Wednesday

In my almost-completed survey of what great thinkers have said about literature’s impact upon audiences, I recently arrived at a new clarity at what I think my book accomplishes. Below is an excerpt from the introduction that explains why I find the approach useful.

I can report that the book is currently being reviewed by professional colleagues, whose feedback is proving invaluable. I am also putting together a book proposal to send out to publishers. There’s finally an end in sight for a project that I have been actively working on for ten years and indirectly working on my entire career.

Excerpt from Better Living through Literature: A 2500-Year-Old Debate

When we reflect on the richness that comes from studying readers’ responses to literature, we encounter a theoretical problem. How can one generalize about literary impact when individual responses are so unpredictable and vary so widely?

The task is so daunting that we can understand why Reader Response Criticism and Reception Theory have never caught on as widely as other theoretical approaches, such as (in their time) New Criticism and Deconstruction and New Historicism.

Some scholars have argued that we should skip readers altogether. In literary criticism’s formalist period following World War II, W.K. Wimsatt and Monroe Beardsley contended that to judge a work based on its emotional affect was to commit “the affective fallacy.” They found it cleaner and a more purely aesthetic and intellectual exercise to look only at the text.

The rest of the world isn’t interested in clean, however. Most people who have had intense literary experiences aren’t willing to dismiss them as irrelevant. And then there are English teachers, who have a stake in figuring out why their students respond as they do to a work, and parents, who have the same concern regarding their children and teenagers. If people really thought that literature didn’t change human behavior, we wouldn’t see the censorship battles that never go away. Messy or not, we’ve got to grapple with whether literature affects human behavior and, if so, how.

To arrive at answers, my approach is threefold. By showing, side by side, those thinkers who believe that literature packs a punch, I strive to reassure readers who are distressed that so many regard literature as a luxury rather than a necessity. Or as Sir Philip Sidney puts it, who are distressed at how “poor poetry, which from almost the highest estimation of learning is fallen to be the laughing-stock of children.”

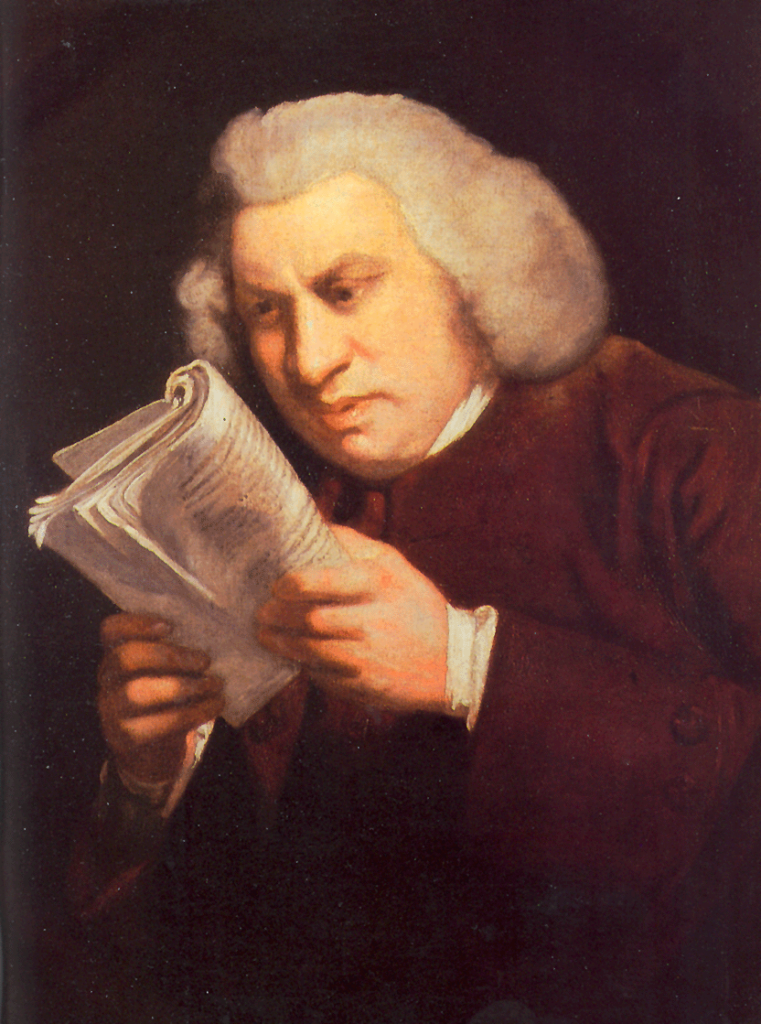

By surveying the arguments that have been put forth, you will get a sense of literature’s potential and, in the theories that resonate most with your own reading experiences, find the weapons to fight back against the naysayers. If you hope literature can fend off cultural barbarians who want to trash revered traditions, Sidney, Samuel Johnson, Matthew Arnold, and Allan Bloom will come to your aid. If you see literature as vital in bringing about a more just and equitable society, you’ll find allies in W. E. B. Du Bois, Bertolt Brecht, Herbert Marcuse, Rachel Blau DuPlessis, Wayne Booth, and Martha Nussbaum.

Second, while some of the theories conflict, certain recurring themes reveal themselves. Throughout the book we will be tracking common concerns as we search for, in Shakespeare’s phrase, “a great constancy.”

Finally, because no generalized observation can do full justice to idiosyncratic responses—often there’s no predicting what an individual reader will take away from a specific work—I present the thinkers as models. Their theories, like yours, are based on their immersion in specific works, and seeing how these men and women have derived meaning from intense reading encounters can help you in your own analysis. My final chapter is devoted to helping you arrive at customized insights about why you love the books you love and hate the books you hate.