Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Friday

I retired from full time college teaching in 2018 at the age of 68, and what I miss most is watching students using literature to grapple with foundational questions. In my final years, after 40 years in the classroom, I was still being surprised and delighted at the variety of ways that students would use poems and stories to find meaning in their lives.

What I don’t miss is having to grapple with the challenges posed by new technologies, whether they be cellphones, zoom classes, or fake essays written by ChatGPT. The best teachers, as they always have, find ways to rise to the occasion, but there comes a point when one becomes tired of always having to rise. It’s enough of a task just to get students to engage with and reflect upon old-fashioned books.

In my defense, I’ll note that my wariness about the potential of new technology to enhance learning is not new. Three hundred years ago a writer was voicing his skepticism on this very issue.

The writer I have in mind is Jonathan Swift. In Book III of Gulliver’s Travels, published in 1726, Swift directs his satire against the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, a.k.a. the Royal Society. While a remarkable organization, like all such organizations it was prone to excesses and misguided enthusiasms. After all, when you openly invite new projects and proposals, you will see genuinely whacky theories arise. In his book Swift imagines scientists attempting to extract sunbeams from cucumbers, soften marble into pillows and pincushions, replace silkworms with spiders (and having them eat brightly colored flies so the threads will be pre-dyed), mix paint by smell, reassemble original food stuffs from excrement, and build houses from the top down (in imitation of the bee and the spider).

And then there’s a project that anticipates ChatGPT, the Artificial Intelligence program that produces seemingly acceptable writing from material it pulls from the internet. Swift’s engineer wants to build a contrivance by which “the most ignorant person, at a reasonable charge, and with a little bodily labor, might write books in philosophy, poetry, politics, laws, mathematics, and theology, without the least assistance from genius or study.” In other words, anyone can be an expert with this gizmo, which is twenty feet square and fills up an entire room:

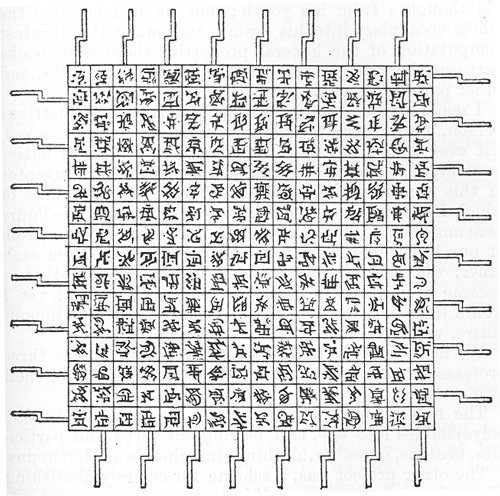

The superficies was composed of several bits of wood, about the bigness of a die, but some larger than others. They were all linked together by slender wires. These bits of wood were covered, on every square, with paper pasted on them; and on these papers were written all the words of their language, in their several moods, tenses, and declensions; but without any order.

The engine works as follows:

The pupils, at his command, took each of them hold of an iron handle, whereof there were forty fixed round the edges of the frame; and giving them a sudden turn, the whole disposition of the words was entirely changed. He then commanded six-and-thirty of the lads, to read the several lines softly, as they appeared upon the frame; and where they found three or four words together that might make part of a sentence, they dictated to the four remaining boys, who were scribes. This work was repeated three or four times, and at every turn, the engine was so contrived, that the words shifted into new places, as the square bits of wood moved upside down.

The inventor explains that he “had emptied the whole vocabulary into his frame, and made the strictest computation of the general proportion there is in books between the numbers of particles, nouns, and verbs, and other parts of speech.” For their part, the students spend six hours a day gathering these sentence fragments, which are then transcribed into a large folio. The inventor hopes that those rich materials will “give the world a complete body of all arts and sciences.”

Of course, like any start-up tech company, he can’t do this without more money. Also, like ChatGPT and other such systems, he plans to make uncompensated use of other people’s written work. Gulliver reports that this 18th century tech bro hopes “that the public would raise a fund for making and employing five hundred such frames in Lagado, and oblige the managers to contribute in common their several collections.”

The issues that Swift raises are also being encountered by ChatGPT. As a New Yorker article points out, one only gets an approximation of knowledge from the program, which the author compares to a blurry JPEG image:

Think of ChatGPT as a blurry JPEG of all the text on the Web. It retains much of the information on the Web, in the same way, that a JPEG retains much of the information of a higher-resolution image, but, if you’re looking for an exact sequence of bits, you won’t find it; all you will ever get is an approximation. But, because the approximation is presented in the form of grammatical text, which ChatGPT excels at creating, it’s usually acceptable.

ChatGPT-generated work is acceptable only in appearance. To be sure, an essay produced through such a means can look professional and polished, but often one only needs to look at the footnotes to realize how fake it all is. I don’t know if the story is apocryphal about a lawyer being disbarred after his AI generated brief was discovered to have phony footnoted precedents, but I do know that teacher acquaintances have told me that essays quickly fall apart once one compares footnotes created in this fasion with the actual source material.

Gulliver’s account of a frame filling up an entire room is reminiscent of the early days of large mainframe computers, and certainly we’ve found ways to shrink everything down while automating the scribe work that the narrator describes. But the reason that Swift can anticipate the future problems technology will encounter, along with the abuses that will arise from it, is because he understands that human beings are deeply flawed. For all the promises of the Enlightenment, the Age of Reason, and the Scientific and Technological Revolutions, he knows that science and technology and social engineering (including “A Modest Proposal for Preventing the Children of Poor People from Being a Burthen to Their Parents or Country”) will founder the moment we start ignoring human nature.

Man is an animal capable of reason, Swift often said, with emphasis on the “capable.” As often as not, people’s soaring ambitions are sabotaged by their own pride and by their capacity for sin. Swift talks about the philosopher who, because he gazes only at the stars while walking, ends up in the gutter.

All of which is to say that teachers should never forget the human element in their profession. To overlook it results in shoddy teaching.