Wednesday

Recently Scott Dickers, publisher of The Onion, visited St. Mary’s as part of our annual Mark Twain series, run by my colleague Ben Click. Not surprisingly, he talked about fake news, including instances where people have believed Onion articles to be real. Chinese media, for instance, took seriously its designation of Kim Jung Un as “the sexiest man alive.”

Asked about the effectiveness of political satire, Dickers acknowledged that it doesn’t accomplish much substantively but is great at rejuvenating political activists. Democracies require constant vigilance, he noted, and the The Onion plays a role in alerting us to issues.

In the question and answer period, I asked whether members of the The Onion read Jonathan Swift and was gratified to learn that the satirist is admired there, especially his attention to detail in his own fake items.

Given how my students packed the gym to hear Dickers, I haven’t been surprised by their enthusiasm for Swift. To provide insight into what the Augustan satirist means to millennials, I report here on three end-of-semester essays I received on Gulliver’s Travels.

Alex Weber discussed the dangers that insecure men pose to the world, which is no small issue these days (although to be fair to Donald Trump, he’s far from the first). Swift’s use of size in the first two books captures the difference between small and large-minded individuals.

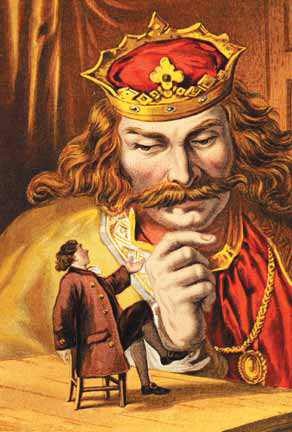

In the Lilliputians episode, inflated egos are more humorous than dangerous. That’s because, at least by our standards, there’s only so much damage that a three-inch Lilliputian can do. Therefore we laugh at the Lilliputian king’s claims of greatness.

In the preamble to the articles that Gulliver must sign, for instance, the Lilliputian king sounds like a leader who has boasted about having the largest inauguration and the most successful first 100 days ever. Note the wonderfully understated parenthetical expression, which reads like one of those chyrons that cable news sometimes runs when reporting a Trump falsehood:

Golbasto Momarem Evlame Gurdilo Shefin Mully Ully Gue, most mighty Emperor of Lilliput, delight and terror of the universe, whose dominions extend five thousand blustrugs (about twelve miles in circumference) to the extremities of the globe; monarch of all monarchs, taller than the sons of men; whose feet press down to the center, and whose head strikes against the sun; at whose nod the princes of the earth shake their knees; pleasant as the spring, comfortable as the summer, fruitful as autumn, dreadful as winter: his most sublime majesty proposes to the man-mountain, lately arrived at our celestial dominions, the following articles, which, by a solemn oath, he shall be obliged to perform.

The satire turns grim when Gulliver is amongst the Brobdingnagian giants, however, and we see how small people can turn to murderous force when trying to prove that they are big. To impress the king, Gulliver offers him the secrets of gun powder:

In hopes to ingratiate myself further into his majesty’s favor, I told him of “an invention, discovered between three and four hundred years ago, to make a certain powder, into a heap of which, the smallest spark of fire falling, would kindle the whole in a moment, although it were as big as a mountain, and make it all fly up in the air together, with a noise and agitation greater than thunder. That a proper quantity of this powder rammed into a hollow tube of brass or iron, according to its bigness, would drive a ball of iron or lead, with such violence and speed, as nothing was able to sustain its force. That the largest balls thus discharged, would not only destroy whole ranks of an army at once, but batter the strongest walls to the ground, sink down ships, with a thousand men in each, to the bottom of the sea, and when linked together by a chain, would cut through masts and rigging, divide hundreds of bodies in the middle, and lay all waste before them. That we often put this powder into large hollow balls of iron, and discharged them by an engine into some city we were besieging, which would rip up the pavements, tear the houses to pieces, burst and throw splinters on every side, dashing out the brains of all who came near. That I knew the ingredients very well, which were cheap and common; I understood the manner of compounding them, and could direct his workmen how to make those tubes, of a size proportionable to all other things in his majesty’s kingdom, and the largest need not be above a hundred feet long; twenty or thirty of which tubes, charged with the proper quantity of powder and balls, would batter down the walls of the strongest town in his dominions in a few hours, or destroy the whole metropolis, if ever it should pretend to dispute his absolute commands.” This I humbly offered to his majesty, as a small tribute of acknowledgment, in turn for so many marks that I had received, of his royal favor and protection.

When Alex and I discussed the scene, Trump’s bombing of Syria came immediately to mind. Unfortunately, the fact that pundits and much of the media swooned over the attack indicates that they are not as “big” as the Brobdingnagian ruler, who is horrified:

The king was struck with horror at the description I had given of those terrible engines, and the proposal I had made. “He was amazed, how so impotent and groveling an insect as I” (these were his expressions) “could entertain such inhuman ideas, and in so familiar a manner, as to appear wholly unmoved at all the scenes of blood and desolation which I had painted as the common effects of those destructive machines; whereof,” he said, “some evil genius, enemy to mankind, must have been the first contriver.”

Alex wondered whether the insecurities Swift describes grow out of despair over “man’s relative unimportance in stark contrast to the vastness of the cosmos.” Upon reflection, I recalled some dark Swift poems where identity splinters and disintegrates into an amorphous mass (“A Description of a City Shower,” “A Beautiful Young Nymph Going to Bed”). A fear of being nothing–emptiness at the core–may help explain Trump’s bombast.

Michael Barrett had another interesting take, arguing that Gulliver learns what it’s like to move from an entitled member of society to an oppressed minority. As long as Gulliver is a giant in the land of the Lilliputians, he can see himself above politics and shrug off slights. When he is a Lilliputian in a land of giants, on the other hand, he must be hyperaware of everything around him. It’s the difference between driving while white and driving while black.

Only Gulliver, having once been privileged, can’t make the adjustment. Instead, he insists on seeing himself as a giant in Book II and then as a houyhnhnm in Book IV. In addition to his efforts to impress the Brobdingnagian king with gun powder, he returns to England thinking he is big:

As I was on the road, observing the littleness of the houses, the trees, the cattle, and the people, I began to think myself in Lilliput. I was afraid of trampling on every traveler I met, and often called aloud to have them stand out of the way, so that I had like to have gotten one or two broken heads for my impertinence.

In Book IV, meanwhile, he is so intent on distinguishing himself from the yahoos that he approves of the houyhnhnm plan to exterminate them and he himself uses their skin for sails on his ship. In other words, his identification with the powerful prompts him to commit atrocities against his own kind.

Michael and I talked about the cognitive dissonance that arises when formerly privileged people find themselves to be powerless. They will sometimes do anything to keep from admitting that they are small or yahoo. This may help explain why unemployed coal miners and factory workers voted for Trump: they imagine they are up there with him lambasting The Establishment.

In a third essay, political science major Sam Baker was excited that the yahoo-houyhnhnm divide essentially pits Hobbes’s “man in a state of nature” against Plato’s philosopher kings. Political theorists, Sam realized, often mistakenly think that a system exists that can overcome human fallibility. Those totalitarians, fundamentalists, and ideologues who demand a pure and total way of organizing society may, out of frustration, ultimately endorse yahoo genocide. The houyhnhnms banish Gulliver as Plato banishes poets, and Robespierre, Hitler, Stalin, and ISIS enacted more extreme measures.

Sam actually found some relief in Swift’s observation that no system can be perfect and that we must always live with flaws. Acknowledging this could open our politics to compromise.

In short, one of history’s greatest satirists is getting my students to grapple with foundational issues.