Wednesday

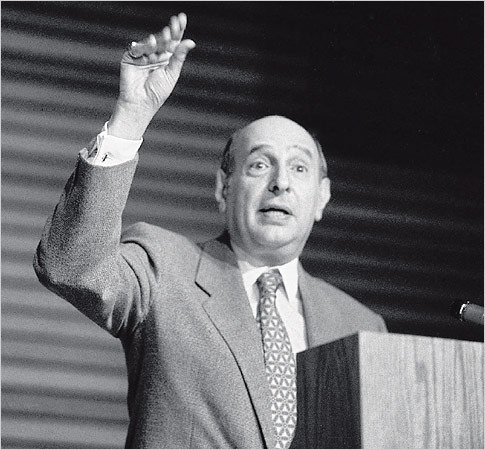

As I continue to revise my book on the 2500-year-old debate over whether literature makes our lives better, I’m looking again at my chapter on Allan Bloom, whose Closing of the American Mind was at the center of the culture wars of the late 1980s and early 1990s. I actually prefer his Shakespeare’s Politics, written 23 years earlier, which is more specific about why we need the bard in our lives.

Writing in 1964—before the counter-culture and student protests—Bloom begins his book with the same lament that he voices later: students aren’t reading the books that will serve them the best:

The most striking fact about contemporary university students is that there is no longer any canon of books which forms their taste and their imagination. In general, they do not look at all to books when they meet problems in life or try to think about their goals; there are no literary models for their conceptions of virtue and vice.

The problem, as Bloom sees it, is that students instead are guided by “popular journalism” and “the works of ephemeral authors.” Bloom doesn’t name any of these authors, but my sense from the following passage is that Bloom’s bar is so high that the number of non-ephemeral authors is in single digits:

The civilizing and unifying function of the peoples’ books, which was carried out in Greece by Homer, Italy by Dante, France by Racine and Moliere, and Germany by Goethe, seems to be dying a rapid death. The young have no ground from which to begin their understanding of the world and themselves, and they have no common education which forms the core of their communication with their fellows.

Bloom can’t entirely get away with saying that the academy has abandoned Shakespeare because it never has. To this day, the bard still reigns supreme in Introduction to Literature courses, and every English Department has well-attended courses devoted to him. Bloom therefore shifts his critique and complains that people aren’t teaching Shakespeare correctly. In 1964, he had a point as the New Critics focused more on issues of form (say, looking for image patterns) than on Shakespeare as a guide for life. By contrast, writing as a political philosopher, Bloom believes Shakespeare can make us better citizens and better leaders.

Because I have been so immersed in the uses to which literature can be put, I recognize Bloom’s influences. Like Plato, he believes that life should be about the true and the good although he doesn’t agree with Plato’s suspicion of poetry. Like Aristotle, he sees literature as essential to the life of the state although he gives poetry the same status as philosophy, which it’s not clear that Aristotle does. Bloom channels the Roman poet Horace in seeing poetry’s mission as to simultaneously delight and instruct, writing,

Shakespeare wrote at a time when common sense still taught that the function of the poet was to produce pleasure and that the function of the great poet was to teach what is truly beautiful by means of pleasure.

Continuing on with influences, Bloom seems to be channeling Elizabethan Renaissance courtier Sir Philip Sidney when he talks about poetry inspiring heroic virtue. He is also following Samuel Johnson, who in his own work on Shakespeare wrote, “From his writings indeed a system of social duty may be selected.”

Bloom sounds very Johnsonian when he writes that Shakespeare “shows most vividly and comprehensively the fate of tyrants, the character of good rulers, the relations of friends, and the duties of citizens.” When Shakespeare does so, “he can move the souls of his readers, and they recognize that they understand life better because they have read him; he hence becomes a constant guide and companion.”

Or at least, Bloom says, that’s the way it was in the old days, when people turned to Shakespeare “as they once turned to the Bible.”

Finally, Bloom uses the same descriptor for today’s students that Matthew Arnold applied to the economically successful but culturally illiterate middle class. Because the classic authors are no longer “a part of the furniture of the student’s mind, once he is out of the academic atmosphere,” we have the following situation:

This results in a decided lowering of tone in their reflections on life and its goals; today’s students are technically well-equipped, but Philistine.

Moving from Shakespeare to poetry in general, Bloom says that literature moves people as other forms of knowledge cannot. For instance,

The philosopher cannot move nations; he speaks only to a few. The poet can take the philosopher’s understanding and translate it into images that touch the deepest passions and cause men to know without knowing that they know. Aristotle’s description of heroic virtue means nothing to men in general, but Homer’s incarnation of that virtue in the Greeks and Trojans is unforgettable. This desire to depict the truth about man and to make other men fulfill that truth is what raises poetry to its greatest heights in the epic and the drama.

This means, Bloom says, that the poet has a double task: “to understand the things he wishes to represent and to understand the audience to which he speaks. He must know about the truly permanent human problems; otherwise his works will be slight and passing.”

Bloom examines three Shakespeare plays and the lessons they teach. Merchant of Venice and Othello, he notes, are both set in Venice, which had the reputation as a place “where the various sorts of men could freely mingle, and it was known the world over as the most tolerant city of its time.” It’s interesting that Bloom, who later would be cited by conservatives in the culture wars, actually seems to be advocating for a liberal social vision. By showing us Shylock and Othello in their full humanity, he says, Shakespeare makes it harder for us to be anti-Semites and racists:

Shakespeare, while proving his own breadth of sympathy, made an impression on his audiences which could not be eradicated. Whether they liked these men or not, the spectators now knew they were men and not things on which they could with impunity exercise their vilest passions.

Writing in the heyday of the civil rights movement, Bloom could be talking about America when he writes,

Venice did not fulfill for [Shylock and Othello] its promise of being a society in which men could live as men, not as whites and blacks, Christians and Jews, Venetians and foreigners.

In Julius Caesar, as Bloom sees the play, Shakespeare provides a profound lesson in politics. In Caesar, one finds an extraordinary mixture of vision and practicality that only the greatest leaders possess:

Caesar seems to have been the most complete political man who ever lived. He combined the high-mindedness of the Stoic with the Epicurean’s awareness of the low material substrate of political things. Brutus and Cassius could not comprehend such a combination…

Yet the two conspirators also provide important models for future generations:

Their failure, as Brutus saw, won them more glory than Octavius and Antony attained by their success, for they are the eternal symbols of freedom against tyranny. They showed that men need not give way before the spirit of the times; they served as models for later successors who would reestablish the spirit of free government. Their seemingly futile gesture helped, not Rome, but humanity. Men in foreign lands and with foreign tongues have looked to Rome and to the defenders of its liberties against Caesarism for inspiration in the establishment of regimes which respect human nature and encourage a proud independence. Shakespeare, the teacher of the Anglo-Saxon world, was such a man.

In Shakespeare, Bloom writes, we have someone who can understand the need for a free man and good citizen to balance “his passions and his knowledge.” Art speaks to our emotions, political theory to our reason, and Shakespeare, maybe better than anyone, brought the two together:

We are aware that a political science which does not grasp the moral phenomena is crude and that an art uninspired by the passion for justice is trivial…[W]e sense that [Shakespeare] has both intellectual clarity and vigorous passions and that the two do not undermine each other in him. If we live with him a while, perhaps we can recapture the fullness of life and rediscover the way to his lost unity.

I wonder if I would have followed Bloom if I had had him as a teacher in college. Because I was turned off by the way my Carleton English professors—in the grip of New Criticism—separated literature out from history and life, I chose instead to major in history, turning only to English in graduate school. On the other hand, I might have been turned off by the way that Bloom insisted that other authors had to be put down in order to raise the greatest authors up. There’s an elitism there that doesn’t sit well with me, even though I deeply respect Bloom’s project.