If he were alive today, Shakespeare would be in the streets celebrating the Supreme Court’s Friday ruling in favor of same sex marriage. In Twelfth Night he all but gives us two same sex marriages.

I say “all but” because, of course, Shakespeare couldn’t outwardly advocate such marriages. He was writing 400 years too early and he had to resolve the play with a series of socially acceptable couplings. While the comedy is still unfolding, however, we can imagine other possibilities. Not for nothing is the play subtitled “What You Will.”

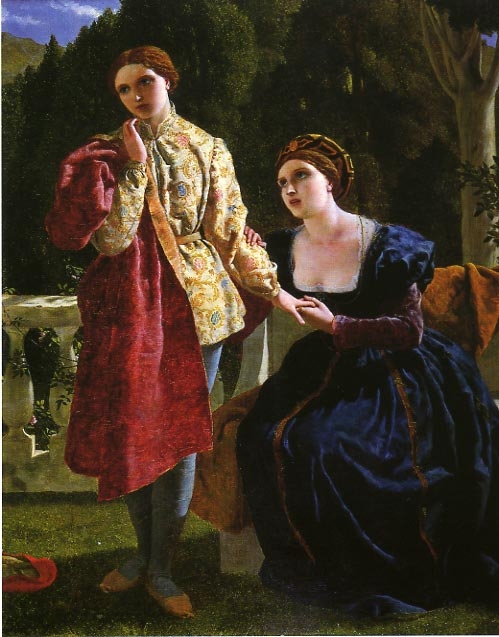

First, we encouraged to imagine a marriage between Count Orsino and Cesario. Yes, of course Cesario is really Viola disguised as a man. When we’re watching the scene where Orsino instructs Cesario/Viola to woo Olivia on his behalf, however, we see someone who looks like a man–and who, in Elizabethan times, would actually have been played by a man–expressing desires for another man:

Viola: I’ll do my best

To woo your lady:

[Aside]

yet, a barful strife!

Whoe’er I woo, myself would be his wife.

At the end of the play, we have a scene reminiscent of those marriage proposals we have been watching on television ever since courts and state legislatures began allowing same sex marriage: a man proposing to (someone who looks like) a man:

Orsino: Boy, thou hast said to me a thousand times

Thou never shouldst love woman like to me.

Viola: And all those sayings will I overswear;

And those swearings keep as true in soul

As doth that orbed continent the fire

That severs day from night.

Orsino:

Give me thy hand…

And further on:

Here is my hand: you shall from this time be

Your master’s mistress.

Or course, Orsino doesn’t have the Supreme Court to step in and tell him that it would actually be permissible for him to marry a man. He’s stuck with heterosexual marriage. As long as Viola wears male clothing, however, he can dream a little longer, pretending that she is still Cesario:

We will not part from hence. Cesario, come;

For so you shall be, while you are a man…

Television has been showing us women proposing to women as well as men proposing to men. Here’s Olivia doing the same:

Olivia to Viola:

Cesario, by the roses of the spring,

By maidhood, honor, truth and every thing,

I love thee so, that, maugre [despite] all thy pride,

Nor wit nor reason can my passion hide.

Of course, technically Olivia thinks Viola is a man so she’s within the letter of the law. One can make a strong argument, however, that Oliva falls in love, not with a man, but with a strong woman. Viola is the kind of woman that Olivia dreams of being so it makes sense that she would be drawn to her. Marrying Sebastian is like settling for a consolation prize, necessitated because the Supreme Court has not yet changed what is permissible. Olivia can’t have Viola so she settles for her twin.

I’ve written in the past that Twelfth Night’s magic lies in the way it allows us to dream of relationships that were not allowed by the society of the time. Shakespeare, who understood human beings as well as anyone ever has, knew that conventional definitions don’t capture the full complexity of who we are. Orsino at times feels like a woman trapped inside a man’s body and Viola embraces the chance to dress up like a man. Antonio is definitely gay and Sebastian, who is “near the manners of my mother,” may swing both ways. Biologist Milton Diamond of the University of Hawaii, noting that “biology loves diversity, society hates it,” has documented many of the different ways that x and y chromosomes have lined up in the human body, and that doesn’t even bring in social influences. Through the chaos of his comedy, Shakespeare acknowledges that complexity.

Sadly, in 1602 humans couldn’t express their full multidimensionality. The play may seem to end happily with a string of heterosexual weddings, but the fool’s final song is filled with grim visions of marriage. In one, a man realizes that he can’t find happiness by swaggering like a man: “But when I came, alas! to wive, By swaggering could I never thrive.” In another, it sounds like someone–he or the wife–must get drunk to handle the marriage bed: “But when I came unto my beds,/With toss-pots still had drunken heads.”

As the fool puts it, once one grows up and gets married–comes into “man’s estate”–the reality of life is “the wind and the rain.” Feste punctuates the grimness of this reality with his refrain, “And the rain it raineth everyday.”

On Friday, the sun came out.