Wednesday

Nina George’s Little Paris Bookshop (2015) has a great premise: a “book apothecary” sizes up customers and presents them with the books that they need. Sometimes he refuses to sell them a book that will be bad for them.

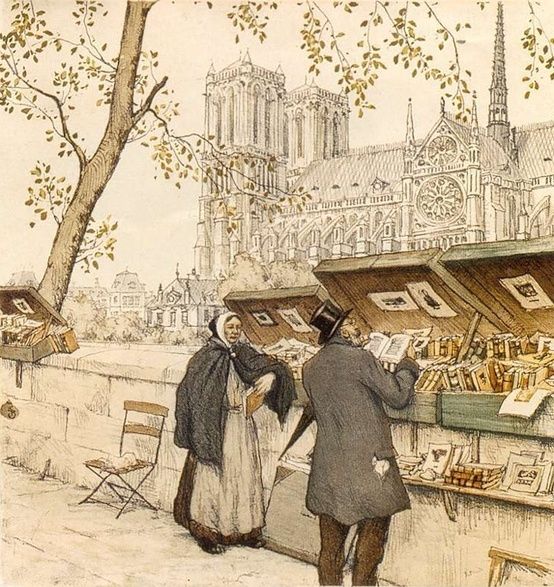

Jean Perdu—“Perdu” means lost—owns a boat bookstore that is parked at a Paris quay. While he’s good at prescribing books for other people, he himself is an emotional mess, his mistress having left him without explanation 20 years previously. When he finally discovers that she left because she had terminal cancer and wanted to spare him, he unmoors his boat for the first time in decades and sets off for the south of France, recommended by the French for spiritual healing.

Little Paris Bookshop presents us with an idealized France, one mediated through Marcel Pagnol, Jean Gabin, Monsieur Hulot, and The Red Balloon. At times it verges on the overly precious and sentimental, and the Washington Post pans it, finding it lightweight:

As Perdu comments to his sidekick: “Some novels are loving, lifelong companions; some give you a clip around the ear; others are friends who wrap you in warm towels when you’ve got those autumn blues. And some . . . well, some are pink candy floss that tingles in your brain for three seconds and leaves a blissful void.” He should know.

I wouldn’t go this far. The line separating delicate and poetic from pink candy floss can be a fine one, and Little Paris Bookstore has its moments. I want to focus here, however, on George’s exploration of literature’s curative powers.

The maladies that Perdu cures resemble the “Heavenly hurt” and “imperial affliction/Sent us of the air” that Emily Dickinson describes in “There’s a certain slant of light,” psychic woundings of a sensitive Proustian soul. Perdu sets them forth as follows:

“I wanted to treat feelings that are not recognized as afflictions and are never diagnosed by doctors. All those little feelings and emotions no therapist is interested in, because they are apparently too minor and intangible. The feeling that washes over you when another summer nears its end. Or when you recognize that you haven’t got your whole life left to find out where you belong. Or the slight sense of grief when a friendship doesn’t develop as you thought, and you have to continue your search for a lifelong companion. Or those birthday morning blues. Nostalgia for the air of your childhood. Things like that.” He recalled his mother once confiding in him that she suffered from a pain for which there was no antidote…

It was precisely to relieve such inexplicable yet real suffering that he had bought the boat, which was a working barge then and originally called Lulu; he had converted it with his own hands and filled it with books, the only remedy for countless, undefined afflictions of the soul.

Perdu describes how he selects his books:

“Books are like people, and people are like books. I’ll tell you how I go about it. I ask myself: Is he or she the main character in his or her life? What is her motive? Or is she a secondary character in her own tale? Is she in the process of editing herself out of her story, because her husband, her career, her children or her job are consuming her entire text?”

Max Jordan’s eyes widened.

“I’ve got about thirty thousand stories in my head, which isn’t very many, you know, given that there are over a million titles available in France alone. I’ve got the most useful eight thousand works here, as a first-aid kit, but I also compile courses of treatment. I prepare a medicine made of letters: a cookbook with recipes that read like a wonderful family Sunday. A novel whose hero resembles the reader; poetry to make tears flow that would otherwise be poisonous if swallowed.”

We watch Perdu’s method at work as he interacts with a television advertising saleswoman:

Perdu asked the customer, whose name was Anna, a few questions. Job, morning routine, her favorite animal as a child, nightmares she’d had in the past few years, the most recent books she’d read…and whether her mother had told her how to dress.

Personal questions, but not too personal. He had to ask these questions and then remain absolutely silent. Listening in silence was essential to making a comprehensive scan of a person’s soul.

Perdu determines that Anna is concealing “pains and longings” behind “a fog of words”:

Monsieur fished out these words. Anna often said: “That wasn’t the plan” and “I didn’t count on that.” She talked about “countless” attempts and “a sequence of nightmares.” She lived in a world of mathematics, an elaborate device for ordering the irrational and personal. She wouldn’t allow herself to follow her intuition or consider the impossible possible.

Yet that was only one part of what Perdu listened out for and recorded: what was making the soul unhappy. Then there was the second part: what made the soul happy. Monsieur knew that the texture of things a person loves rubs off on his or her language too.

After listening, Perdu chooses a number of books from what he refers to as his “Library of Emotions”:

“Here you go, my dear. Novels for willpower, nonfiction for rethinking one’s life, poems for dignity.” Books about dreaming, about dying, about love and about life as a woman artist. He laid out mystical ballads, hard-edged old stories about chasms, falls, peril and betrayal at her feet. Soon Anna was surrounded by piles of books as a woman in a shoe shop might be surrounded by boxes.

Perdu wanted Anna to feel that she was in a nest. He wanted her to sense the boundless possibilities offered by books. They would always be enough. They would never stop loving their readers. They were a fixed point in an otherwise unpredictable world. In life. In love. After death.

The prescription proves successful:

Her tense shoulders slackened, her thumbs unfurled from her clenched fists. Her face relaxed.]

She read.

Monsieur Perdu observed how the words she was reading gave shape to her from within. He saw that Anna was discovering inside herself a sounding board that reacted to words. She was a violin learning to play itself.

The interaction between Perdu and his customers catches my eye because I listen to my students in a similar way. I’m skeptical of his super observation powers, however, because, in my experience, finding matches is more of a trial and error affair. I am constantly surprised at which works will strike home, as in the case of the Afghan vet who used Sir Gawain and the Green Knight to deal with traumatic war experiences.

I’ll also add that literature can do more than handle “little feelings and emotions no therapist is interested in.” Many of my students have big issues—death of loved ones, broken homes, debilitating illnesses—and literature proves up to the challenge time and again. Why settle for a vague ennui when you can be fixing broken bones?

It’s worth noting that books aren’t what save the various characters in Little Paris Bookshop, starting with Perdu. It’s almost as if, for George, books are a nice frill, fun to vacation in but not capable of heavy lifting. It’s revealing that Perdu prescribes nonfiction, not novels or poems, for “rethinking one’s life.” Literature may be good for emotional expression, in other words, but leave it to discursive prose for action.

Despite her enthusiasm for literature, Nina George sells it short.