Thursday

While Stephen King’s The Stand is noteworthy for its depiction of a pandemic, I’m going to focus today on another King novel because of the way it shows us our penchant for forgetting past cataclysms, thereby ensuring that we will repeat our mistakes. IT is only too relevant in showing how this forgetting works.

To be accurate, I shouldn’t say “we” since many people acknowledged the COVID-19 threat from the first. They remembered all too well our encounters with the bird flu, the swine flu and the Ebola virus and were calling for immediate action in January. The nation’s pandemic team would have done the same had not Trump disbanded it. I’m therefore just talking about those who allowed Donald Trump to erase whatever disagreeable memories they had of past epidemics. Forgetting was easy because it was what they wanted.

It has been a costly forgetting. Because of administrative inaction, America will soon be the world epicenter of the virus and could lose upwards of two million people.

In IT, the memories erased are America’s periodic explosions of unbridled violence. The story takes place in Derry, Maine—think of it as one of the idealized small towns found in 1960s sitcoms—which is haunted by a homicidal clown living under the streets. At one point he tears apart a child, at another he murders a gay man.

In my recent course on supernatural horror, I discussed how the gothic is a powerful literary vehicle for capturing how we repress sides of ourselves we are unwilling to face up to. Unwilling to acknowledge that much of its history has featured horrific violence, from Indian massacres to land grabs to lynchings, America has invented a benign history. What we repress turns toxic, however, and the gothic specializes in such toxicity, thereby making it a favored genre for our truth-telling poets and novelists.

In IT, a group of marginalized kids forms “The Losers Club” and manages to defeat the clown. (Their parents, dulled by worldly cares, can’t see what’s going on.) Then they forget what they have seen and done, just as America forgets the bloodshed.

Here’s a personal example of such forgetting. I was raised in, and now have retired to, Franklin County, Tennessee, which includes the township of Estill Springs. For most people in the county, Estill Springs is little more than a blip in the road between Winchester (our county seat) and Tullahoma (the county seat in adjoining Coffee County). Growing up, I never heard about the 1918 Estill Springs lynching in which an innocent man was chained to a tree by a mob, which used hot irons to force a confession, tortured him, and then burned him alive. This occurred a mere 35 years before my family moved to the area.

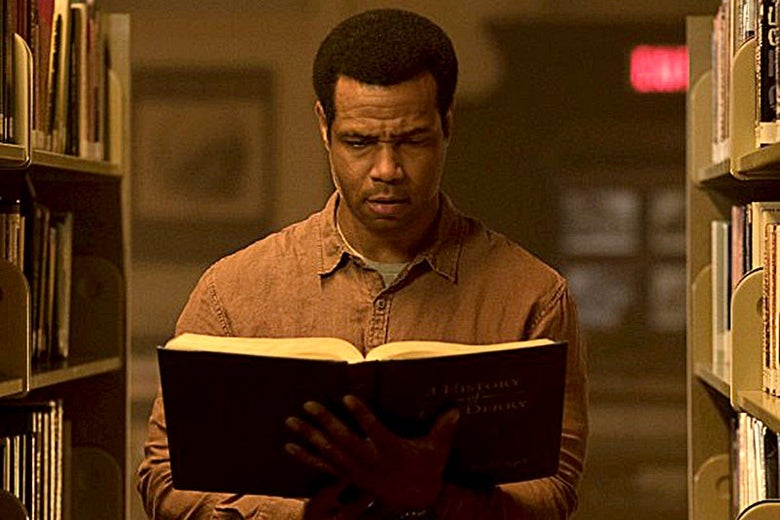

In It, the only kid who stays in Derry and the only kid who does not forget is the African American member. Later, as the town’s librarian, Mike Hanlon makes it his mission to watch for the clown’s return. Mike also becomes Derry’s unofficial historian and discovers outbreaks of violence every 27 years. Sure enough, 27 years after the defeat of the clown, he sees a recurring pattern of renewed violence and concludes that the clown is back. He reassembles the group and refreshes their memories. They must battle the clown again, this time without the protection of childhood innocence.

It makes sense that Hanlon is African American because, as such, he is far more likely to acknowledge America’s violent past. The privilege of whiteness is that it can close its eyes to violence whereas people of color do not have this luxury. The club, however, made a blood pact as children to fight the violence should it ever recur, and they honor their commitment as adults.

COVID-19 is not racial violence, but it’s an extremely disagreeable truth. Because it takes courage to face up to such truths, Trump is showing himself to be the most cowardly president in American history. Given that he’s determined to do nothing more than screw things up, forget about him. Americans must face up to COVID-19 on their own, doing whatever we can. to help. At the very least, we can wash our hands, maintain social distance, and (if we have the option) shelter in place.

When we are in the grip of fear, we can become monsters. This is the central message of IT (and of King’s fiction generally). Each member of the Losers Club, first as a child and then as an adult, must grapple with his or her particular fears if the clown is not to gain supremacy. All but one rise to the occasion. This is what heroism looks like.