Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Sunday

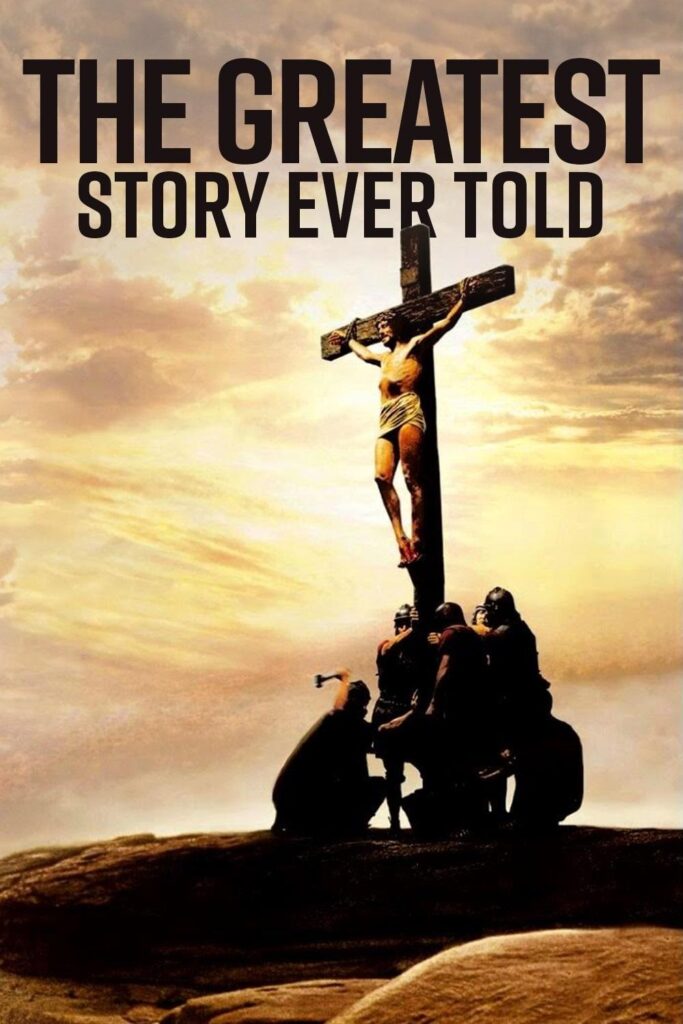

I report today on a forthcoming article, “The Greatest Story Ever Told: How Theism Predicts Christianity,” co-written by Robin Collins and Joshua Rasmussen. Collins, a close friend who teaches philosophy at Messiah College, shared it with me, and I love how it emphasizes the “story” part of the Christian story.

Collins and Joshua Rasmussen argue that the power of the story, rather than historical testimony, is the best evidence that the Jesus narrative actually happened. As Collins writes, “this argument has become the cornerstone of my Christian faith, with other arguments—such as the Apostolic witness to the Resurrection—serving as confirmation rather than foundation.”

Collins and Rasmussen start by noting that, while various scraps of historical evidence exist about Jesus’s ministry, death, and resurrection, an event so extraordinary requires more than scraps. After all, would we believe it if today someone claimed that “their leader, Achmed, was the Holy Spirit who was born of a Virgin and witnessed to be alive in the flesh after being executed for sedition in Iran”? It is because the Christian story has worked so powerfully on the world, the authors conclude, that it can be seen as something more than a fiction.

Their argument starts with the premise—which to be sure atheists will not buy—that God exists and that this deity is omniscient, omnipotent, and perfectly good. Robin, deeply knowledgeable about physics as well as philosophy and religious studies, has elsewhere made scientific arguments for the existence of God, being (as his Wikipedia entry notes) a leading advocate for the Fine-Tuning argument. According to this, life as we know it “could not exist if the constants of nature—such as the electron charge, the gravitational constant and others – had been even slightly different.” In other words, the universe is tuned specifically for life.

But set that aside to return to the story argument. The authors argue that

if someone believed in an omnipotent, omniscient, and perfectly good God (or something sufficiently similar) and knew other relevant things about the world but had never heard the Christian story, they would have strong reason to expect that somewhere in the world a historical incarnation and atonement occurred, since these events develop great value in the greatest kind of story.

Why is this? Well, such a God would want to give “the greatest possible gift (God’s self) to us in the greatest possible way—specifically by providing a way for ourselves to be united with God so that our identity as a person is a finite expression of God’s self while we still retain our own individuality.”

So how would a deity provide us with such a gift given that God is infinite whereas we ourselves experience “lack of knowledge, limited powers, and moral fragility”? The mystery of the incarnation, where God became flesh and dwelt among us, speaks to this. As the authors put it, “for God to enact such a personal life, God would need to assume and act from a limited, human perspective.” Only if God makes God’s self accessible is it possible for humans to see the way clear to becoming at one with God. Christians call this atonement (at-one-ment).

At this point the article looks more closely into the shape of Jesus’s life, which comes to us in the powerful and very relatable guise of story. If our unity with God requires some sort of identification, then we must see God undergo our own experience “of profound suffering—something like (say) a humiliating death by crucifixion.” After all, only if we see God enacting the virtues under the “most extreme type of circumstances” can we imagine taking that path ourselves. Otherwise, as the authors point out, we would not see those virtues as “strong enough for the most difficult life situations people face.”

It is by sharing in these virtues, the authors write, that “we are freed from the forces that hinder moral and spiritual growth (i.e., are “saved from sin”), since living in alignment with the highest virtues is incompatible with destructive tendencies.” The transformation that is subsequently brought about “restores our connection with the divine and brings us into deeper harmony with ultimate reality.”

And further on:

God takes on finite form in a unique way in each one of us. Thus, each person becomes a unique expression of God’s infinite being within the constraints of their finite life. In this way, as we grow in relationship with others, we also grow in our participation in God’s life.

In a passage that brings to mind Dante’s Paradiso, the authors imagine this individual participation continuing on in the afterlife:

Like a great story, this vision of the afterlife is not static but endlessly dynamic. Rather than a mere continuation of earthly existence, it is an eternal deepening of divine participation. Each person, reflecting an inexhaustible aspect of God, will continue to manifest and experience divine beauty in ever-greater ways. This view aligns with C. S. Lewis’s conception of the heavenly state, in which each person will eternally know and praise God, communicating some infinite aspect of divine beauty that no other creature can fully express. Since divine beauty is infinite, this process of knowing, praising, and participating in God’s life will never be exhausted.

Lovers of fiction will notice that confronting trials, experiencing suffering, overcoming evil, and growing into maturity is the template for many of our greatest stories, as well as for the universal journey of the hero myth identified by C.J. Jung and Joseph Campbell. If what Collins and Rasmussen say is right, then in reading such stories we are seeking confirmation of a deeper truth, one that takes us out of ourselves and puts us in touch with something transcendent. This is the case even when the stories are not overtly religious. As Lisa Simpson would say, they embiggen us.

Burrowing more deeply into the Christian plot, the authors note that a great story

provides hope—an expectation that suffering and struggle have meaning. Christianity offers this story element by framing life’s hardships as part of an epic journey, one filled with character development, unexpected plot twists, and, ultimately, the triumph of good. This perspective links earthly life with the afterlife, showing that suffering and vulnerability are not meaningless but serve a role in shaping us and deepening our connection with the divine.

Furthermore, just as we are not static as readers, nor are we static in the process of atonement. By following Jesus’s example and precepts—especially (as Paul laid them out) faith, hope, and love—we participate in the great drama. The authors conclude,

[I]f God exists, we have reason to expect reality to reflect the greatest kind of story—one rich in meaning, transformation, and ultimate resolution. A great story involves struggle, character development, and the triumph of good over evil. We can see Christianity as a dynamic display of these elements in their highest form, including the Incarnation and Atonement, where the highest being enters history and overcomes the greatest kind of human suffering to provide the greatest kind of good (unity with God) in a dynamic way.

Here are Collins and Rasmussen recapping their article:

1. The highest good for human beings is union with God.

2. All else being equal, the greatest kind of story would include the highest good for human beings—namely, union with God—and achieve this in the most effective way.

3. Achieving these goods most effectively requires the Incarnation, in which God becomes human and exemplifies the highest virtues in the most challenging circumstances, inviting humanity to participate in these virtues, resulting in a participatory atonement. (For Christians, the highest virtues are faith, hope, and love.)

4. Therefore, all else being equal, the greatest story will include both the Incarnation and Atonement.

The authors touch on other issues, including why the Christian story occurred when it did (it has something to do with the reach of the Roman empire and the public nature of executions) and how it relates to the stories of other religions. Given how the phrase Collins and Rasmussen use brings to mind those 1960s religious blockbusters whose triumphalism I’ve always detested—Hollywood glitz seems at odds with the Christian message—I hasten to point out that they are fairly ecumenical in their claims. There are incarnation and atonement elements in other religions as well.

In the end, what I appreciate most about the piece is how it further enhances my appreciation both for the Christian story and for fiction in general. Truth is to be found at the core of both.