Monday

Liberals cheered for a number of the recent Supreme Court rulings but not for the decision, in Glossip v. Gross, to allow the continued use of midazolam in executions. I have been appalled at the way that the Supreme Court has supported the death penalty over the years, and this was their latest refusal to face up to the horrors. Charles Dickens would share my disgust.

I’ll discuss Dickens after laying out the case against midazolam. The sedative has entered the picture now that states must scramble to find lethal injection drugs. That’s because more and more pharmacies are refusing to allow their drugs to be used for lethal injection, prompting states like Oklahoma to either illegally import drugs or experiment on prisoners with drug cocktails. Ever since sodium thiopental has become unobtainable, a New Yorker article by Lincoln Caplan notes, there have been “dozens of accounts of ghastly executions by lethal injection gone wrong.” One of the worst occurred with Clayton D. Lockett.

Here’s Caplan’s account of what occurred in the Lockett execution:

The executioner tried and failed at least twelve times to find a usable vein for delivering the injections. After almost an hour, he found one in Lockett’s groin. Seven minutes after he was given a sedative, Lockett was deemed ready and the lethal drugs were administered. Then, “after being declared unconscious,” lawyers for the death-row inmates told the Court, “he began to speak, buck, raise his head, and writhe against the gurney.” A federal appeals court reported, “In particular, witnesses heard Lockett say: ‘This shit is fucking with my mind,’ ‘Something is wrong,’ and ‘The drugs aren’t working.’ ” About twenty minutes later, when the state’s director of corrections thought that Lockett had not received enough of the execution drugs to kill him and that there was not enough of them left to complete the execution, he ordered the executioner to stop administering any drugs. Lockett died anyway soon after.

Caplan explains why Oklahoma’s use of midazolam, regardless of what the Supreme Court declared, is problematic:

In executing Lockett, Oklahoma used for the first time as the anesthetic a sedative called midazolam, which is usually employed to treat serious seizures and severe insomnia. As lawyers for the inmates told the Court, it has no pain-relieving properties, hasn’t been approved by the F.D.A. to maintain general anesthesia in surgical operations, and has a “ceiling effect,” meaning that even a large dose of it may not put someone under. The lawyers noted that “there are actual scientific and medical data demonstrating that midazolam cannot reliably render a person unconscious and insensate for purposes of undergoing surgery.”

I consider the death penalty itself to be “cruel and unusual punishment,” but certainly it is so when extreme pain enters the picture. Yet whenever executions go wrong, we hear voices on the extreme right crowing that the prisoners are getting a taste of their own medicine. These are the same voices that have applauded America torturing prisoners.

Here’s where Dickens comes in. His fear is that executions dehumanize the rest of us. We see such dehumanization at work in the mob scenes in Oliver Twist.

There is little to be said in favor of Bill Sikes and Fagan, one of whom dies when he is being chased by a mob and the other when he is officially hanged. Although Dickens gets us to hate both men, he uses their deaths to call the death penalty into question.

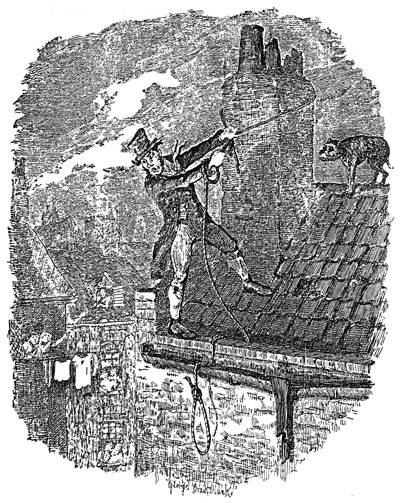

According to my son Toby, who taught Oliver Twist in a Charles Dickens class last semester, the author was appalled at the carnival atmosphere that surrounded public hangings. In the presence of death, spectators lose their individuality and are overtaken by a kind of animal ferocity. We see the process at work as the mob chases Sikes:

Of all the terrific yells that ever fell on mortal ears, none could exceed the cry of the infuriated throng. Some shouted to those who were nearest to set the house on fire; others roared to the officers to shoot him dead. Among them all, none showed such fury as the man on horseback, who, throwing himself out of the saddle, and bursting through the crowd as if he were parting water, cried, beneath the window, in a voice that rose above all others, ‘Twenty guineas to the man who brings a ladder!’

The nearest voices took up the cry, and hundreds echoed it. Some called for ladders, some for sledge-hammers; some ran with torches to and fro as if to seek them, and still came back and roared again; some spent their breath in impotent curses and execrations; some pressed forward with the ecstasy of madmen, and thus impeded the progress of those below; some among the boldest attempted to climb up by the water-spout and crevices in the wall; and all waved to and fro, in the darkness beneath, like a field of corn moved by an angry wind: and joined from time to time in one loud furious roar.

The “man on horseback,” Toby pointed out to me, is Harry Maylie, a sympathetic character who will marry Rose. Yet in this scene, he loses his name and is barely distinguishable from the others.

The mob scene that continues is reminiscent of those found in Barnaby Rudge and Tale of Two Cities:

There was another roar. At this moment the word was passed among the crowd that the door was forced at last, and that he who had first called for the ladder had mounted into the room. The stream abruptly turned, as this intelligence ran from mouth to mouth; and the people at the windows, seeing those upon the bridges pouring back, quitted their stations, and running into the street, joined the concourse that now thronged pell-mell to the spot they had left: each man crushing and striving with his neighbor, and all panting with impatience to get near the door, and look upon the criminal as the officers brought him out. The cries and shrieks of those who were pressed almost to suffocation, or trampled down and trodden under foot in the confusion, were dreadful; the narrow ways were completely blocked up; and at this time, between the rush of some to regain the space in front of the house, and the unavailing struggles of others to extricate themselves from the mass, the immediate attention was distracted from the murderer, although the universal eagerness for his capture was, if possible, increased.

The mob gets their hanging. Through an accidental slip of the rope that he is using for escape, Sikes accidentally hangs himself. The mob, we assume, is satisfied.

But to make sure that we don’t feel too good about what has happened, Dickens has the faithful Bulldog leaps to be with his master. He sees something in the man, even if the rest of us don’t. He misses and his brains are dashed out on the pavement.

The official hanging of Fagan also has its down moment:

Day was dawning when they again emerged. A great multitude had already assembled; the windows were filled with people, smoking and playing cards to beguile the time; the crowd were pushing, quarrelling, joking. Everything told of life and animation, but one dark cluster of objects in the centre of all—the black stage, the cross-beam, the rope, and all the hideous apparatus of death.

Dickens understands that, when we succumb to our bloodlust, we put ourselves on a level with the basest forms of humanity. We become lost in a Kurtzian heart of darkness and are capable of anything.

That’s what’s at stake in these Supreme Court cases. Our hope, which was Dickens’s hope, is that our humanity will assert itself and we will end this barbaric practice. The good news is that more and more states are doing so.