Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Monday

Yesterday I presented a talk entitled “‘Being Alive Is the Magic’: The Spiritual Vision That Shapes Francis Hodgson Burnett’s Secret Garden” to our church’s Sunday Forum. One of the ideas I explored was the power of imagining to change the future.

In Friday’s post, I quoted from my friend John Gatta’s book Green Gospel, where he warns about the danger of environmental pessimism. Hopelessness, he says, can become “a self-fulfilling stance, even amounting to another form of climate denialism if it ends in passive resignation or despair.” To counter such hopelessness, he advises imagining visions of a sustainable future. In doing so, we “enlarge our capacity for hope.”

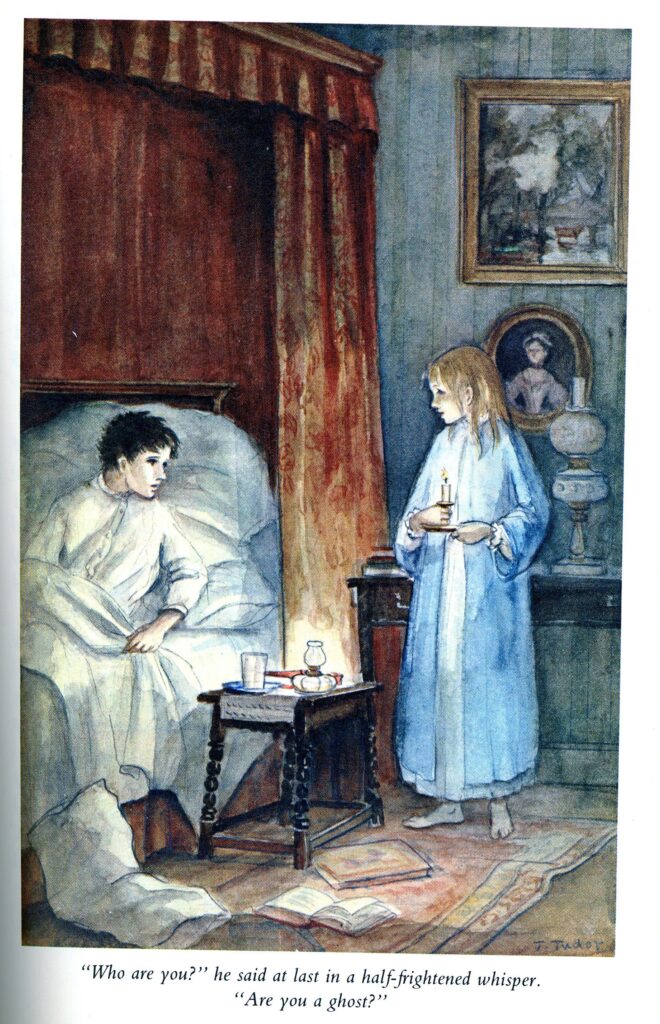

We see the power of such imagining in a moving scene in Secret Garden. Ten-year-old Colin Cravens has been convinced, by others and by himself, that he is a permanent invalid who is going to die. When Mary Lennox tells him about the secret garden, however, he begins seeing the world, and his own prospects in it, in a new way. At this stage in their relationship, however, Mary isn’t sure that she can trust him with her greatest secret, which is that she has found a way into the garden.

What she does, therefore, is engage him in a process of imagining what the garden must be like. I share the following passage because I think it can provide a model for what Gatta has in mind. If we imagine green energy policy might accomplish—and do so in a way that is not empty wish fulfillment but acknowledges the challenges involved—then perhaps we can help bring about a version of the transformations that we witness in the book: which is a dying garden brought back to life, a disagreeable girl whose heart is opened, and a young invalid who learns, not only to walk, but to run.

So here’s Mary pulling Colin into the imagining process:

“Oh, Mary!” he said. “Oh, Mary! If I could get into it I think I should live to grow up! Do you suppose that instead of singing the Ayah song—you could just tell me softly as you did that first day what you imagine it looks like inside? I am sure it will make me go to sleep.”

“Yes,” answered Mary. “Shut your eyes.”

He closed his eyes and lay quite still and she held his hand and began to speak very slowly and in a very low voice.

“I think it has been left alone so long—that it has grown all into a lovely tangle. I think the roses have climbed and climbed and climbed until they hang from the branches and walls and creep over the ground—almost like a strange gray mist. Some of them have died but many—are alive and when the summer comes there will be curtains and fountains of roses. I think the ground is full of daffodils and snowdrops and lilies and iris working their way out of the dark. Now the spring has begun—perhaps—perhaps—”

The soft drone of her voice was making him stiller and stiller and she saw it and went on.

“Perhaps they are coming up through the grass—perhaps there are clusters of purple crocuses and gold ones—even now. Perhaps the leaves are beginning to break out and uncurl—and perhaps—the gray is changing and a green gauze veil is creeping—and creeping over—everything. And the birds are coming to look at it—because it is—so safe and still. And perhaps—perhaps—perhaps—” very softly and slowly indeed, “the robin has found a mate—and is building a nest.”

And Colin was asleep.

Because they have this hopeful vision, Colin and Mary are willing to put in the work, both to save the garden and to get well. It all begins with imagining.