Thursday

My colleague Jeff Hammond, a national authority on Puritan poetry and a much lauded writer of reflective essays, recently gave a stirring defense of the liberal arts for our parents-alumni weekend. Jeff’s observations dovetail very nicely with Percy Shelley’s Defence of Poetry, which I happen to be teaching at the moment. Watching poetry getting shunted aside by people more interested in a narrow utilitarianism, Shelley distinguishes between “reasoners and mechanists” on the one hand and creative types on the other. These reasoners and mechanists are the forerunners of vocational education and they have limited vision. Poetry, by contrast, has a broad utility. “Whatever strengthens and purifies the affections, enlarges the imagination, and adds spirit to sense,” Shelley says, “is useful.”

By Jeffrey Hammond, Professor of English and George B. and Willma Reeves Distinguished Professor in the Liberal Arts at St. Mary’s College of Maryland

As most of you know, St. Mary’s College of Maryland celebrated its 175th anniversary last year. That was a perfect occasion for devoting the Reeves Lecture to the liberal-arts mission that the College pursues. I hoped to articulate what, at the most basic level, a liberal arts education is all about. But a hurricane intervened — and the lecture was cancelled. Since our mission has not changed in the past year, however, I’ve decided to give that talk tonight. Maybe I’m a year off – but who’s to say that a 176th anniversary is any less significant than a 175th?

Besides, defending the liberal arts is an especially fitting topic for a Reeves Lecture. Willma Reeves, the founder of these lectures, was a passionate believer in a liberal education. From my conversations with her, I’m certain that she would have been amazed – and alarmed — by rumors that this kind of education is dying out. For some people, the end can’t come soon enough: for them, the phrase “liberal arts” is a synonym for hopeless impracticality and certain unemployment. Maybe they’re imagining young aristocrats strolling across manicured lawns while carrying gilt-edged editions of Cicero. That fantasy contains a dose of Anglophobia, a defensive reaction against the whole Oxbridge Thing and everything it stands for – or used to. After all, we’re Americans: a practical people, a nation of doers. We didn’t create the greatest country on earth by cow-towing to snooty traditions.

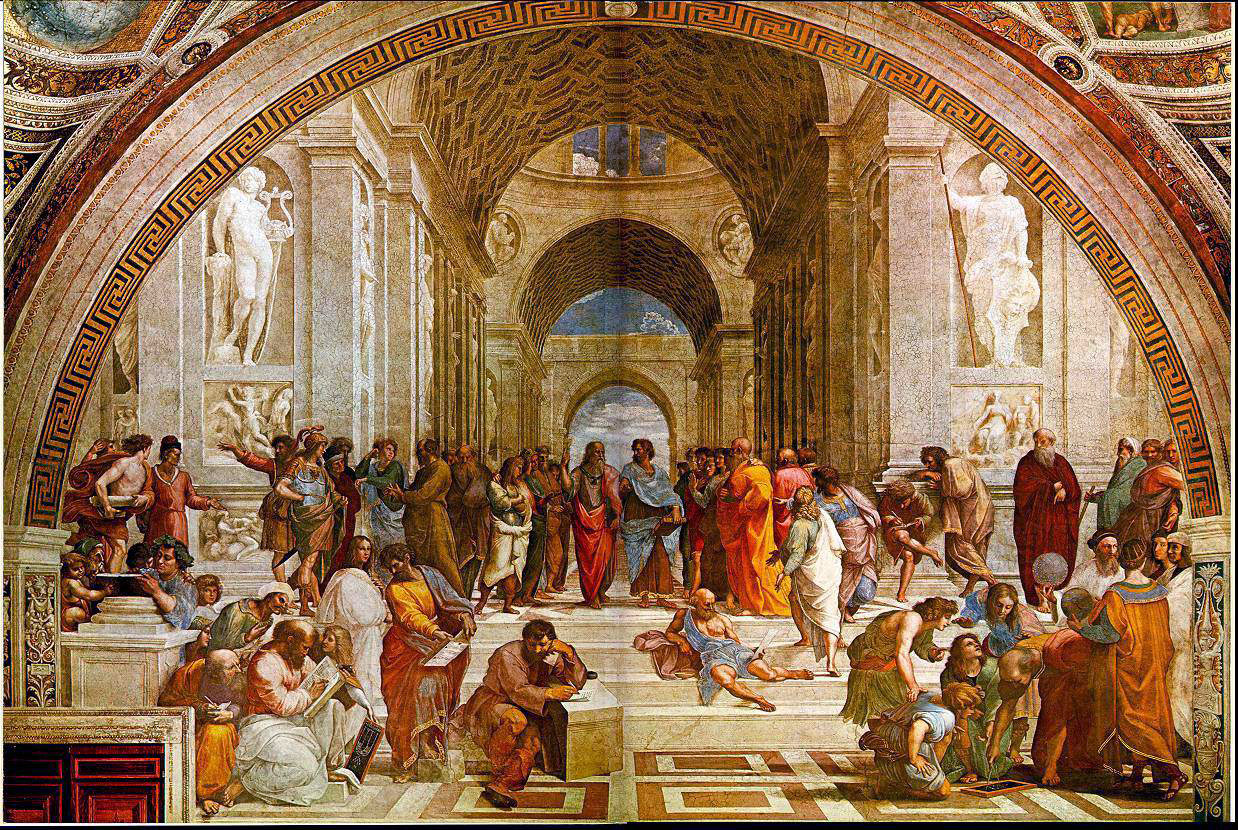

Actually, charges of elitism have some historical validity: originally, the liberal arts were elitist. Among the ancient Greeks and Romans who conceived them, the artes liberales were pursuits limited to “free men” — liberi in Latin. In contrast to occupational crafts, these “arts” were pursued by people for whom work was deemed unworthy activity. That’s why the word “school” comes from the ancient Greek scholé, which meant “leisure.” Only rich young Athenians had the leisure to chat with Socrates. Ditto for his student Plato, whose “academy” was named after a grove and gymnasium that were popular hangouts for idle aristocrats. His student, Aristotle, founded what was called the “peripatetic” school, which meant “walking around”: he allegedly taught while strolling. And the Stoics took their name from the colonnaded porch or stoa that framed the marketplace – another hangout for rich idlers. But here’s the deal: if you’re hanging out or strolling around with a philosopher, you aren’t herding sheep, picking grapes, or pressing olive oil.

The liberal arts reinforced social hierarchies because leisure was necessary for pursuing them. Nowadays they do the flat opposite. Today’s liberal arts education provides access to what was formerly reserved for the most privileged. Considered within the broad sweep of history, this reversal was fairly recent: while it had roots in the nineteenth century, it really took off in the middle of the twentieth, when the G. I. Bill made college affordable to non-elite veterans. The democratizing of the liberal arts is most visible at an institution that a century ago would have been considered a contradiction in terms: a public liberal arts college. But that, of course, is precisely what we are. Because we’re public, you don’t have to be a trust-fund baby to go here. You don’t have to be a legacy, either. As our many first-generation college students show, schools like St. Mary’s have turned the old socio-economic bias of the liberal arts on its head.

So much for claims of elitism. But another belief informs the assumption that the liberal arts are dying. That’s the belief that this kind of education fails to prepare people for jobs. Vocational panic has created huge challenges for liberal arts colleges: many are finding it hard to attract and retain students. St. Mary’s recently had an enrollment crisis of our own – and although we’re pulling out of it, other schools have not been so lucky. By one count, twenty-five liberal arts colleges have closed in the past fifteen years; around 40 more have merged or been absorbed into larger schools. Given this kind of pressure, simply appealing to tradition won’t cut it. We have to do a better job of clarifying and promoting the tangible benefits of a liberal arts education.

We might begin by addressing the charge that liberal arts colleges are out of touch with economic realities. In fact, American higher education had a practical bent from the start. Our first liberal arts colleges were established to train clergy; the so-called “normal” schools that came later were established to train teachers. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the goal of preparing middle-class American youth for meaningful work produced the large state universities established by the Land-Grant Acts of 1862 and 1890. These new universities reinforced a perceived split between idealism and practicality. Colleges, private and often church-affiliated, continued to emphasize the liberal arts. Universities supplemented general education with career training in fields like engineering, medicine, law, and agriculture. Increasingly, universities were construed as “the new” and colleges as “the old.” While universities maintained a core of traditional disciplines, usually housed within a “College of Arts and Sciences,” the liberal-arts focus at small colleges was associated, more and more, with an impractical education.

But were the liberal arts ever really impractical? To answer that requires us to look deeper into the past – and also into human nature. As long as people have been learning things, we’ve been devising schemes for organizing what we’ve learned. In antiquity this ordering of knowledge was pursued most famously by scholars at the great Library of Alexandria, which functioned as a kind of think-tank for the ancient Mediterranean world. By the first century the Roman scholar Varro had organized learning into nine basic categories: logic, grammar, rhetoric, mathematics, geometry, music, astronomy, architecture, and medicine. Eventually, architecture and medicine were dropped from Varro’s list because they described professions rather than disciplines.

Thus arose the seven liberal arts as they were defined throughout the Middle Ages. Logic, grammar, and rhetoric comprised the Trivium, the foundation of language and thinking and therefore of all subsequent learning. The Trivium – roughly equivalent to the humanities, meant “the three ways.” The other four arts – math, geometry, music, and astronomy – formed the Quadrivium, roughly the origin of the sciences. Music might seem out of place there, but the ancients saw music in terms of mathematical proportions that corresponded with the structure of the cosmos.

That’s what the liberal arts originally were. But what, exactly, did they do for those who were able to pursue them? The answer lies in their remarkable range: to study them was to receive an education sufficient for moving through the world with some understanding of virtually everything that one might encounter. This versatility was due to the fact that even from the beginning, the liberal arts were not piles of knowledge so much as a set of tools and methods for acquiring knowledge.

The point was not to amass a specific body of facts, but to learn how to learn – to acquire the ability to teach oneself anything. Consider the degree to which the original liberal arts developed traits that still define a truly educated person. Logic fostered an ability to observe carefully and think critically. Rhetoric fostered an ability to communicate and interpret others’ communications effectively. The other five arts fostered an ability to grasp the relationships among things, whether those things were verbal (as in grammar), numerical (as in mathematics), spatial (as in geometry), sonic (as in music), or celestial (as in astronomy). Despite centuries of intellectual advancement, these basic skills still reside at the heart of a liberal arts education.

It is just here that the practical benefits of a liberal arts education become clearest. The best foundation for a productive work-life is not to learn how to do a particular job, but to learn how to learn. Because strong learners can adapt to new things, they are less dependent on shifting circumstances and current assumptions. Strong learners are especially well suited to functioning in environments where things are constantly changing – environments like today’s world. Precisely because the nature and conditions of work are changing too fast for job-training to keep up with them, a truly practical education cultivates a social, intellectual, and creative flexibility that cannot become outdated.

Perhaps ironically, the business community – for whom filling jobs is the top priority — has been crying out for adaptable, creative people with solid thinking and communication skills: precisely the kinds of people that a liberal education is designed to produce. It was once assumed that studying a particular set of subjects would produce such a person. This wasn’t wrong, exactly — but what really produced the educated person was the process of studying those subjects. Although the liberal arts always fostered valuable qualities and skills, those qualities and skills were rarely spelled out because nobody questioned them. Now, of course, they are being questioned – which means that we need to make them as explicit as we can. At St. Mary’s we’ve defined these skills as “critical thinking, information literacy, written expression, and oral expression.” These skills are timelessly valuable – and those students who attain them are solidly equipped to cope with this challenging job market. Instead of training them for specific jobs, their education has given them something far better: they’ve been prepared for careers.

In an attempt to highlight these qualities and skills, the College is developing vehicles for assessing how well we’re teaching them. But once you move beyond the practical benefits of a liberal arts education, you arrive at an outcome that cannot be so easily assessed: namely, a richer and fuller life. Those traditional liberal-arts questions – the nature of the beautiful and the good, the meaning and sources of happiness, the essence of the human condition – remain as fresh as when they were first posed. Questions like these involve values and ethics — and for that reason, each generation has to answer them for itself.

These deeper questions embody a timelessly indispensable human trait: curiosity. Even in ancient times, when most people lived unimaginably difficult lives, thinkers understood that the full experience of being human ought to consist of something more than just staying alive. What they sensed is affirmed in our DNA: humans are genetically hard-wired to learn, think, and feel a great deal more than is required for survival.

We might even define the essence of being human as this mysterious excess of inner activity. Beavers, for instance, build shelters just as we do, but beavers don’t keep repositioning logs in a new dam to see whether one arrangement is more attractive than another. In short, beavers don’t do aesthetics. Beavers also don’t spend much time pondering the moral significance of what they’re doing or the abstract essence of “damness.” Beavers don’t do ethics or metaphysics, either. Now, this is not to disrespect beavers, but merely to confirm that the predilection to reflect and imagine – and to be aware of ourselves doing so – is the genetic heritage of homo sapiens. Children display this biological imperative in its purest form: everyone knows how much a child enjoys figuring something out or seeing something new.

This innate curiosity is as old as the species – and it has helped us immeasurably. Here’s a special type of flint that is really good for making fire: pass it on. If we plant these seeds and stick around, we’ll get more food than if we simply eat the seeds and move on: pass it on. Gods who establish moral covenants with us are more worthy of our worship than gods who rely on brute force: pass it on. These twin epics in Ionic Greek celebrate not just the glory of war, but the sadness and waste of it: pass them on. Village A, which has better drainage than Village B, lost fewer people to the plague this year: pass it on. And so it goes: so it has always gone.

As improved drainage suggests, even the most idealistic defense of the liberal arts cannot avoid their practical benefits. This suggests that the traditional distinction between theoretical and practical knowledge has always been overstated. Learning for its own sake – an ideal central to the liberal arts tradition – has always had its practical side in the betterment of the human condition. Sooner or later, learning gets applied to something, and often the results are good.

Of course, deciding how learning gets applied is a question of values. The liberal arts tradition is concerned not simply with the acquisition of knowledge, but with the ethics of knowledge. In other words, a liberal education is not just about knowing, but about knowing what’s right. This does not mean that there is a single, liberal arts “position” on any given moral or political issue. Although a liberal education tries to connect values with learning, it does not predetermine the results of that connection. But while it refuses to dictate answers, it insists that moral and ethical questions be part of the conversation.

Here, too, practical outcomes are sneaking their way back in. What could be more practical than learning how to make ethical decisions? Consider all the professional schools – medical schools, law schools, MBA programs – that have been scrambling to add courses in professional ethics to their degree requirements. American higher education is rediscovering an old truth: few things are more practical than consequences, and no assessment of consequences can be restricted to the bottom line of profit. In fact, to provide job training without a liberal education carries some risk. Job training is not usually concerned with ethics and values: it tells you how to do a thing. A liberal education, by contrast, tells you how to do that thing ethically, and even whether it ought to be done in the first place.

Practical benefits also arise when we consider another objection to a liberal arts education. Given an uncertain future filled with challenging problems, why waste time studying anything that lacks immediate application to one or more of those problems? This objection sounds well-intentioned, but it overlooks how problems have always been solved – and that’s the process by which today’s “pure” knowledge often becomes tomorrow’s applied knowledge. The liberal arts emphasis on learning how to learn instills openness to unexpected knowledge – that is, to discoveries that are not short-circuited by a fixation on predetermined outcomes. If we don’t foster basic curiosity, we forfeit these unexpected discoveries and their potential uses down the road. Since the future will always bring unforeseen challenges, we have to keep ourselves open to pure inquiry – to the kind of learning that transcends immediate circumstance and need.

Of course, not every shiny new thing leads to improvements in the quality and ethics of life. The liberal-arts reflection on the proper uses of knowledge is the best antidote for abuses of knowledge. Solutions for future problems will require thoughtful people whose broad learning gives them plenty to draw on. Those problems will require more reflection, not less – and solutions won’t come if the thinking that goes into them lacks imagination or fails to account for as many variables as possible. Deep and wide-ranging reflection does not result from training, narrowly defined. It comes from being liberally educated.

If we weren’t living in a time of economic uncertainty, we wouldn’t even have to remind ourselves that knowing what is true, ethical, and beautiful is a good thing in its own right. In absolute terms, such knowledge requires no defense. Nor does developing a capacity to think for oneself or living a life that transcends material concerns. While the rewards of such a life cannot be quantified, one thing is certain: a life informed by this kind of awareness is fuller and happier than a life lived without it.

At root, a liberal arts education immerses us in human experience. This kind of immersion will never go out of date — presuming, of course, that we humans stick around. I’d even go so far as to say that our sticking around depends on having a critical mass of people who have acquired the qualities and skills fostered by the liberal arts. For one thing, the focus on values prepares people to make decisions that reach beyond their own self-interest. For another, the interdisciplinary experience fostered by the liberal arts – the broad sampling of various ways of knowing – develops people who are able to think outside of personal and professional boxes.

To put this another way, such people can think for themselves — an essential trait of informed and responsible citizens of a democracy. Even the most ardent supporters of a mainly vocational education would agree: our country cannot do without voters who can understand the issues and think for themselves, un-swayed by false or misleading claims. As we’ll see in a few weeks, the health of the American political system depends on the active involvement of such people.

The election aside, there’s no special controversy – or for that matter, originality – in claiming that it’s better to be aware than unaware, independent than dependent, and informed than uninformed. What’s more surprising, perhaps, is the often unrecognized practicality of a liberal arts education. Equally unrecognized is the potential impracticality of a narrowly vocational education. In this volatile global economy, the nature of careers – indeed, of work itself – is rapidly changing. As I have suggested, predominantly vocational education is limited precisely because the world is moving too fast for it. And here’s a seldom acknowledged secret: most jobs – their actual performance – can be learned in a few weeks, provided that the trainee has the curiosity and intellectual flexibility to learn something new. And with that, we’re right back where we started: with traits that a liberal arts education is uniquely positioned to foster.

There is a catch, however. For this kind of education to work, it has to be pursued honestly – and that means with commitment and rigor. If we’re going to counter accusations that a liberal arts education is just a laid-back dabbling in this or that, there’s no place for slacking. Students need to pursue the knowledge and insights gained in their classes as actively and aggressively as they can. There’s no place for slacking among faculty, either. We need to practice the subjects that we preach – to embrace and demonstrate the same passion for lifelong learning that we’re trying to instill in our students.

The fact is, it’s not liberal-arts graduates who are job-disadvantaged, but indifferent liberal-arts graduates. While the abilities and skills cultivated by this kind of education demand a genuine effort to acquire them, it is an effort that will pay huge dividends. We will always need people who can speak, read, and write well, and who can think critically and independently. We will always need people who can find information, grasp the basics of quantitative reasoning, and arrive at conclusions logically. We will always need people who know who and where they are in time and space — who can see beyond their immediate situation to embrace historical, cultural, and global differences. We will always need people who respect the communities they inhabit and the natural environments that sustain those communities. We will always need people who can appreciate artistic beauty, both for its own sake and for the simple reason that fellow humans created it. Most of all, we will always need happy people. The world is a better place when it contains people who are enjoying their lives by living them as fully as possible. In the end, people like this are the best proof that the liberal arts will continue to be, to borrow a phrase from horror movies, “The Education that Wouldn’t Die.”

I was reminded of this by an email that I got from my former SMP student Jeff Tolbert, who graduated some ten years ago. Jeff went on to study folklore at Indiana University, where he’s completing his Ph.D. He attached his first published article: it was a call for folklorists to break out of their academic isolation and engage more directly with the public. Now there’s a guy who has learned some things and wants to apply them to the larger world. And that, in a nutshell, is the liberal arts spirit. As long as there are people who love to learn and want to share what they’ve learned, the liberal arts tradition will retain its value in every sense of the word.