Wednesday

I don’t normally think of painters being influenced by literature, which upon reflection is stupid of me since, like anyone, they would have their vision of the world shaped by a host of influences. For example, my friend Alan Feltus, a painter based in Assisi, first alerted me to the novels of Cormac McCarthy, and I can see connections between his work and McCarthy’s bleak and unsparing vision. I therefore shouldn’t be surprised by a new work out on Van Gogh’s literary influences (thanks to Literary Hub for the alert).

According to Mariella Guzzoni’s Vincent’s Books: Van Gogh and the Writers Who Inspired Him, the artist’s major literary influences were

–Charles Dickens (Christmas Tales)

–Harriet Beecher Stowe (Uncle Tom’s Cabin)

–Guy de Maupassant (Bel Ami)

–Pierre Loti (Madame Chrysanthème)

Other authors mentioned by Van Gogh are Victor Hugo, Shakespeare, and French naturalist authors Emile Zola and Eduard de Goncourt.

In June, 1880, Van Gogh writes of turning to Michelet’s History of the French Revolution along with works by Hugo, Dickens, Stowe, and Shakespeare. Guzzoni notes that the common theme, at least for the first three, is “the fight for freedom and independence; the moral importance of literature; the plight of the poor and deprived.” Shakespeare, of course, finds depth of characters in all classes.

That summer Van Gogh was in Borinange, Belgium where, according to Guzzoni, he had spent a year and a half seeking to console the miners there. Guzzoni writes that “Michelet’s new approach to writing history dared to give the People agency, placing them firmly at the center of the revolutionary dynamic.” The novels meshed well with the history as few art forms are more effective at giving people agency as the novel, as can be seen in Hugo’s Les Miserables, Dickens’s Tale of Two Cities, and Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

The latter work especially hit Van Gogh hard, becoming a kind of “modern gospel” for him when, “in a moment of great doubt, …he rejected the ‘established religious system.’” Van Gogh wrote in his journal,

Take Michelet and Beecher Stowe, they don’t say, the gospel is no longer valid, but they help us to understand how applicable is it in this day and age, in this life of ours, for you, for instance, and for me…

I’ve written about how Stowe contrasts Uncle Tom’s Christianity with that of the slave owners, and it sounds as though Van Gogh may have been making similar distinctions between the mineowners’ and the miners’ faith.

Guzzoni writes that Dickens meant a lot to Van Gogh during his bleakest period:

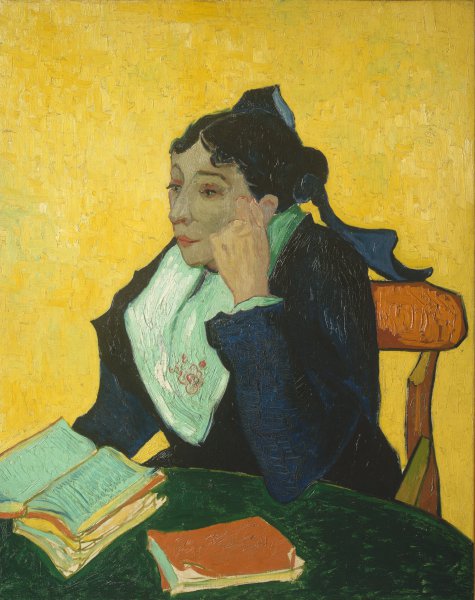

In the darkest moments of his life—self-exiled in the asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence—Vincent finds consolation in Charles Dickens, his favorite British author, “one of those whose characters are resurrections….” In the spring of 1889 he goes back to Dickens’s Christmas Books and Beecher Stowe’s novel. These two old friends, whose landmark works Vincent unites in one of his portraits [see L’Arlésienne above] now offer him positivity and humanitarian sentiments. The ethical and political potential of (literary) art, both in Dickens and in Beecher Stowe, flows naturally in their fiction as examples of clear moral commitment. Art for mankind, Vincent’s artistic credo.

While Dickens’s Christmas tales are indeed uplifting and Uncle Tom is a virtual Christian saint, I find it interesting that Van Gogh likes the far less sentimental Maupassant, Zola and Goncourt as well. To provide a sample, in Maupassant’s Bel Ami, which actually shows up in one of Van Gogh’s paintings and which he recommended to his sister, we see rural life stripped of all romanticism. The villainous protagonist, who makes his way upward by manipulating wealthy women, has taken his new wife to visit his peasant parents in Normandy. His father’s first question is how much the wife is worth, and for her part she wants to leave as soon as possible:

Madeleine did not speak nor did she eat; she was depressed. Wherefore? She had wished to come; she knew that she was coming to a simple home; she had formed no poetical ideas of those peasants, but she had perhaps expected to find them somewhat more polished, refined.

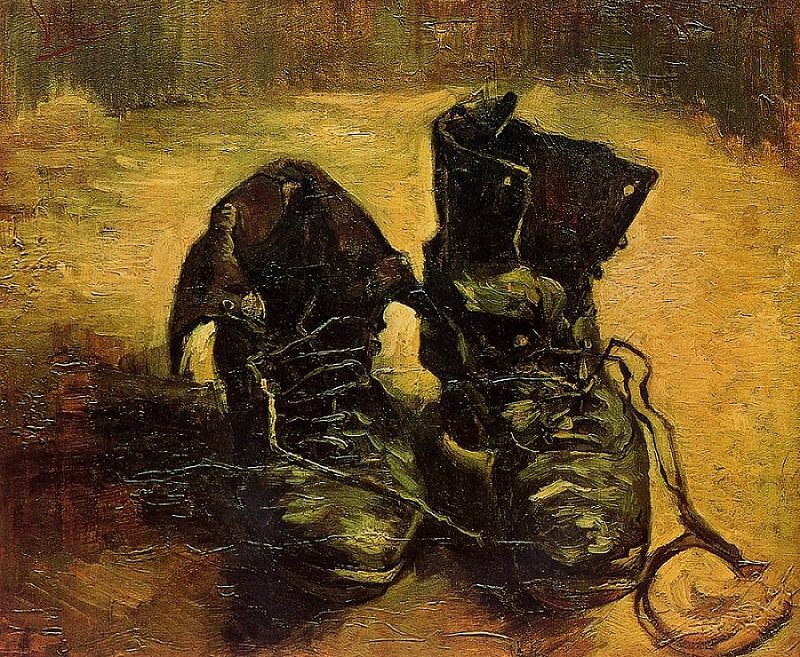

Van Gogh said that Maupassant got him to laugh for the first time in years, and I wonder if he would have found humor in such a passage. His powerful paintings of peasant shoes (see below) are the opposite of polished and refined.

Guzzoni concludes by noting that Van Gogh’s reading played a key role in his “astounding artistic evolution, over a period of just ten years”:

In his passion for books lies part of the energy and creative tension that flows through his art. Faithful friends, sources of inspiration and consolation, safe harbors in rough seas—for Vincent books were all this and more. It is great lesson for us, too, to bring joy in these difficult times.

Amen.