Tuesday

To reward myself after 10 intensive days of grading essays and meeting with students, I spent Saturday rereading Haruki Murakami’s 1Q84, the novel that turned me on to the Japanese novelist. As I did so, I rediscovered a passage that pretty much sums up the rationale for this blog. Maybe Murakami’s bookishness is what hooked me.

The passage involves a math teacher who is also an aspiring novelist. Tengo loves both but, whereas math helps him escape from life, literature provides him with potential solutions for his problems. As Murakami puts it, a novel for Tengo

was like a piece of paper bearing the indecipherable text of a magic spell. At times it lacked coherence and served no immediate practical purpose. But it would contain a possibility.

Here’s the passage:

The world governed by numerical expression was, for him, a legitimate and always safe hiding place. As long as he stayed in that world, he could forget or ignore the rules and burdens forced upon him by the real world.

Where mathematics was a magnificent imaginary building, the world of story as represented by Dickens was like a deep, magical forest for Tengo. When mathematics stretched infinitely upward toward the heavens, the forest spread out beneath his gaze in silence, its dark, sturdy roots stretching deep into the earth. In the forest there were no maps, no numbered doorways.

In elementary and middle school, Tengo was utterly absorbed by the world of mathematics. Its clarity and absolute freedom enthralled him, and he also needed them to survive. Once he entered adolescence, however, he began to feel increasingly that this might not be enough. There was no problem as long as he was visiting the world of math, but whenever he returned to the real world (as return he must), he found himself in the same miserable cage. Nothing had improved. Rather, his shackles felt even heavier. So then, what good was mathematics? Wasn’t it just a temporary means of escape that made his real-life situation even worse?

As his doubts increased, Tengo began deliberately to put some distance between himself and the world of mathematics, and instead the forest of story began to exert a stronger pull on his heart. Of course, reading novels was just another form of escape. As soon as he closed their pages he had to come back to the real world. But at some point Tengo noticed that returning to reality from the world of a novel was not as devastating a blow as returning from the world of mathematics. Why should that have been? After much deep thought, he reached a conclusion. No matter how clear the relationships of things might become in the forest of story, there was never a clear-cut solution. That was how it differed from math. The role of a story was, in the broadest terms, to transpose a single problem into another form. Depending on the nature and direction of the problem, a solution could be suggested in the narrative. Tengo would return to the real world with that suggestion in hand. It was like a piece of paper bearing the indecipherable text of a magic spell. At times it lacked coherence and served no immediate practical purpose. But it would contain a possibility. Someday he might be able to decipher the spell. That possibility would gently warm his heart from within.

Murakami gives us an instance of this narrative magic at work. Tengo grows up not knowing what has happened to his mother. His father, meanwhile, is a man of limited imagination who forces Tengo to accompany him on Sundays when he is collecting fees for Japanese National Television. (Having a child with him makes people more likely to pay up but Tengo hates it.) The boy draws on Oliver Twist to make sense of it all:

My real father must be somewhere else. This was the conclusion that Tengo reached in boyhood. Like the unfortunate children in a Dickens novel, Tengo must have been led by strange circumstances to be raised by this man. Such a possibility was both a nightmare and a great hope. He became obsessed with Dickens after reading Oliver Twist, plowing through every Dickens volume in the library. As he traveled through the world of the stories, he steeped himself in reimagined versions of his own life. The reimaginings (or obsessive fantasies) in his head grew ever longer and more complex. They followed a single pattern, but with infinite variations. In all of them, Tengo would tell himself that this was not the place where he belonged. He had been mistakenly locked in a cage. Someday his real parents, guided by sheer good fortune, would find him. They would rescue him from this cramped and ugly cage and bring him back where he belonged. Then he would have the most beautiful, peaceful, and free Sundays imaginable.

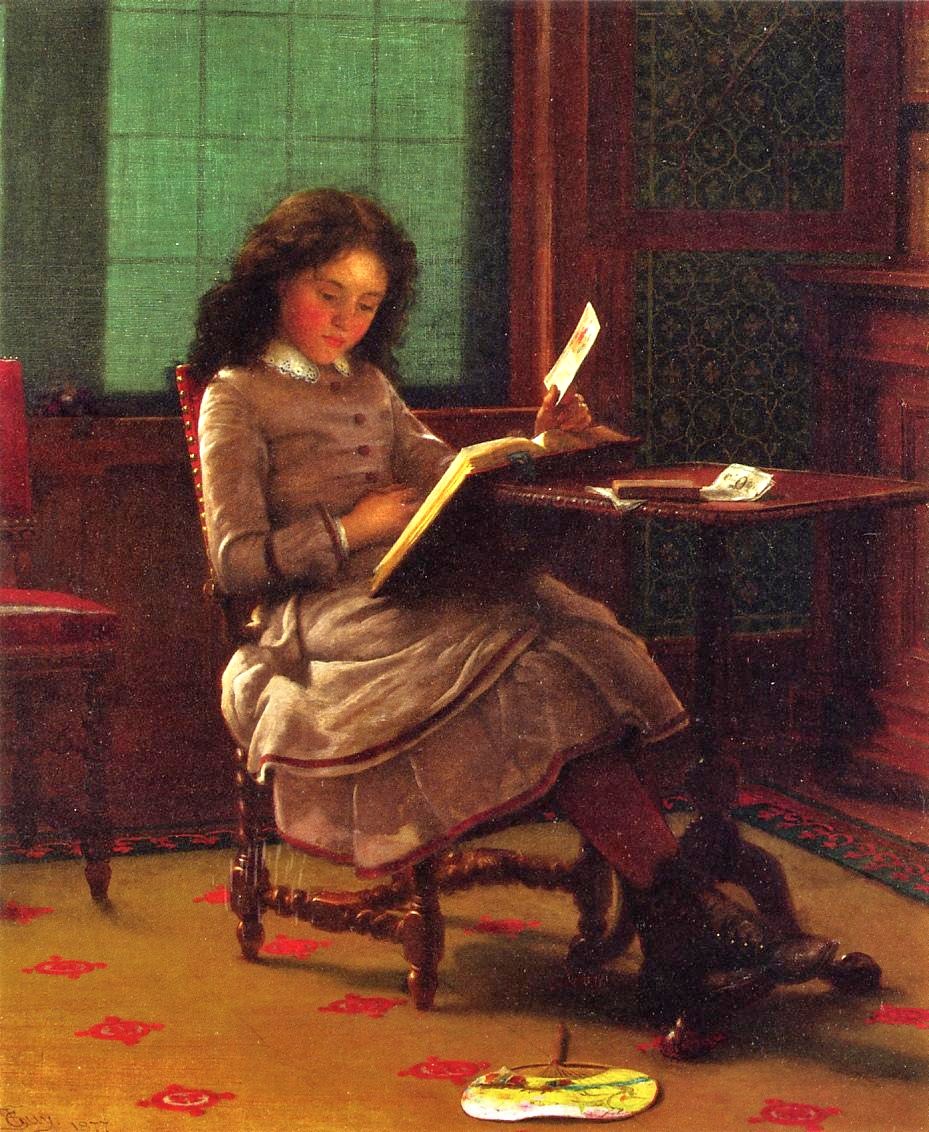

Stories worked this way for me only it was my gender, not my parents, that puzzled me. Because I had more in common with girls than boys, the books that riveted me were those featuring gender ambiguity, like Little Lord Fauntleroy, Ozma of Oz, and, when I reached middle school, Twelfth Night. They seemed to offer up solutions, only just beyond my grasp.

Indecipherable texts of a magic spell.