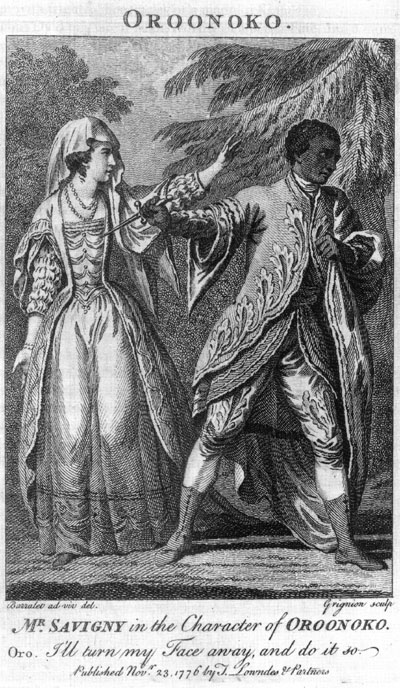

This is a follow-up to yesterday’s post on the debate between liberal bloggers Jonathan Chait and Ta-Nehisi Coates on “race and the culture of poverty.” Today I attempt to be a bit more focused by applying a single passage from Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko to Chait’s contention that we are focusing too much on race in our political battles.

Chait believes that there’s a major problem with liberals automatically tarring conservatives as racist whenever those conservatives embrace policies that hurt minorities. Those policies, he says, may be driven by something besides racism, and he worries that all-encompassing race charges cloud the issues:

Race, always the deepest and most volatile fault line in American history, has now become the primal grievance in our politics, the source of a narrative of persecution each side uses to make sense of the world. Liberals dwell in a world of paranoia of a white racism that has seeped out of American history in the Obama years and lurks everywhere, mostly undetectable. Conservatives dwell in a paranoia of their own, in which racism is used as a cudgel to delegitimize their core beliefs. And the horrible thing is that both of these forms of paranoia are right.

Amongst the liberals that Chait criticizes is Ed Kilgore of Washington Monthly, who has responded that he is actually trying to separate out subjective racism from objective racism. By this he means that it doesn’t matter what conservatives think they think. It doesn’t matter if they tell themselves they are not being racist as they pass Stand Your Ground laws or voter suppression laws that disproportionately impact people of color. What matters is the objective laws themselves.

Chait’s concern about conservatives who plead innocent to charges of racism reminds me of a dark scene from Behn’s work. Oroonoko, called Caesar by the colonialists, has been captured, mercilessly whipped, and had hot pepper rubbed into his wounds after his aborted slave rebellion, His purported friend Trefry, the overseer who assured Oroonoko safe passage, claims that he was given false assurances by Lieutenant Governor Byam. Behn, meanwhile, is worried that Oroonoko will associate her with the tyrannical slave masters. Trefry and Behn both want Oroonoko to think of them as people who wish him well:

We were no sooner arrived but we went up to the plantation to see Caesar; whom we found in a very miserable and unexpressable condition; and I have a thousand times admired how he lived in so much tormenting pain. We said all things to him that trouble, pity, and good-nature could suggest, protesting our innocency of the fact, and our abhorrence of such cruelties; making a thousand professions and services to him, and begging as many pardons for the offenders, till we said so much that he believed we had no hand in his ill treatment: but told us, he could never pardon Byam; as for Trefry, he confessed he saw his grief and sorrow for his suffering, which he could not hinder, but was like to have been beaten down by the very slaves, for speaking in his defense: but for Byam, who was their leader, their head- and should, by his justice and honor, have been and example to ‘em- for him he wished to live to take a dire revenge of him; and said, “It had been well for him if he had sacrificed me instead of giving me the contemptible whip.”

There is a lot going on in this passage, just as there is in our own race debates. Behn and Trefry are the white liberals here, and while they sympathize deeply with Oroonoko, they almost seem more worried that he will see them as Byam-style racists. They therefore badger him into absolving them of responsibility:

[We were] making a thousand professions and services to him, and begging as many pardons for the offenders, till we said so much that he believed we had no hand in his ill treatment…

Oroonoko, who we can assume is more focused on his flayed back than on the guilty feelings of white liberals, nevertheless forgives them. In the passage Behn focuses more on her subjective state than on his objective reality, which is Kilgore’s criticism of Chait.

More positively, having witnessed Byam’s brutality, Behn appears sympathetic with Oroonoko’s expression of black rage. America regularly freaks out when confronted with black rage, real or imagined, which is one reason why Obama has walked so carefully.

Oroonoko’s qualified defense of Trefry is also interesting. Although he notes that he defended Trefry to the other slaves, they were prepared to beat him down for doing so. Why? Because Trefry is the plantation overseer, and although he has treated Oroonoko with respect, he has acted very differently with them. As a result, Trefry appears less racist to Oroonoko than he does to the lower class slaves. This, as I noted in yesterday’s post, is one of Coates’ criticisms of Obama: the president, like Chait but unlike Coates, doesn’t acknowledge the full extent of racism in America.

So who is right here? Behn and Trefry are focused on an issue, their inner guilt, that seems laughably small compared to Oroonoko’s enslavement and death. They can never fully grasp what it’s like being a slave. So chalk one up for Coates.

Then again, they are paying attention to Oroonoko’s suffering, which was very unusual in the 17th century. As I noted yesterday, the real life Behn was so haunted by what happened to the real life Oroonoko that she wrote a book that would go on to play a significant role in the British and American abolition movements. Although Behn is often myopic, her vision of how race, gender, and class inequality undermines even the most promising of friendships stirred the consciences of white audiences. In short, we need Chait as well as Coates.

The conversations about race are so difficult that we must fumble through them together. As we do so, we must avoid both self-righteousness and claims of innocence.

2 Trackbacks

[…] described in past posts (here and here) how Oroonoko tests Aristotle’s assertion that friendship is impossible between people […]

[…] described in past posts (here and here) how Oroonoko tests Aristotle’s assertion that friendship is impossible between people […]