Friday

In a week when schools should be getting underway, I turn to a New York Review of Books interview with one of America’s leading educators. Diane Ravitch, an ardent public education defender and charter school skeptic, cites among her favorite poems two that reflect the high sense of mission that motivates many teachers.:

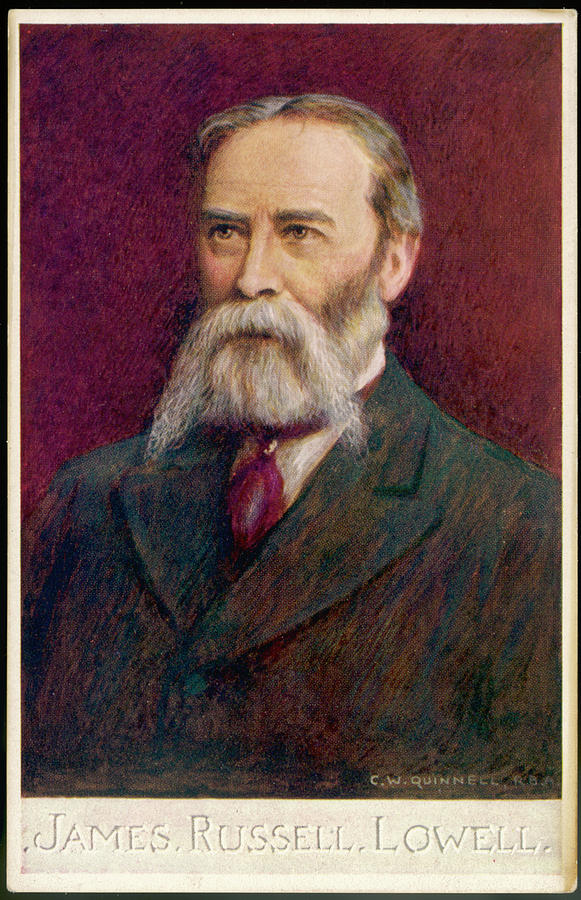

“I confess that I love the golden oldies,” she said, “like [Felicia Hemans’s] ‘Casabianca’ (‘The boy stood on the burning deck: Whence all but him had fled…’) and James Russell Lowell’s ‘The Present Crisis’ (‘Once to every man and nation comes the moment to decide, / In the strife of Truth with Falsehood, for the good or evil side’). I sent that last stanza to Senator Lamar Alexander, who was secretary of education when I worked in the first Bush administration, during the impeachment hearings earlier this year, but it fell on deaf ears.”

These poems, both from the 19th century, don’t get read much any more, but “Present Crisis” is only too timely in the age of Trump. Turning first to the melodramatic “Casabianca” (1826), perhaps it appeals to Ravitch because it is about a child struggling with a moral quandary. “The boy” is so obedient to his captain father that he chooses not to abandon his post upon a burning boat because he hasn’t received permission:

The boy stood on the burning deck,

Whence all but he had fled;

The flame that lit the battle’s wreck,

Shone round him o’er the dead.

Yet beautiful and bright he stood,

As born to rule the storm;

A creature of heroic blood,

A proud, though childlike form.

As the poem progresses, we learn that the father has died. Not knowing this, the boy displays his fortitude—or, if you prefer, his blind obedience:

He called aloud – ‘Say, father, say If yet my task is done?’ He knew not that the chieftain lay Unconscious of his son. ‘Speak, father!’ once again he cried, ‘If I may yet be gone!’ – And but the booming shots replied, And fast the flames rolled on.

Several years ago a student of mine wrote about the 19th century’s fascination with child death, and I’m kicking myself now that I didn’t mention this poem. The climactic final scene is worthy of the death of Charles Dickens’s little Nell or Charlotte Bronte’s Helen Burns:

And shouted but once more aloud,

‘My father! must I stay?’

While o’er him fast, through sail and shroud,

The wreathing fires made way.

They wrapped the ship in splendor wild,

They caught the flag on high,

And streamed above the gallant child,

Like banners in the sky.

There came a burst of thunder sound –

The boy – oh! where was he?

Ask of the winds that far around

With fragments strewed the sea!

With mast, and helm and pennon fair,

That well had borne their part,

But the noblest thing which perished there,

Was that young faithful heart.

I suppose the poem affirms to children that they too are capable of heroism—it certainly advocates for delaying gratification—but I remember encountering parodies when I was in middle school. For instance,

The boy stood on the burning deck

Eating peanuts by the peck

And:

The boy stood on the burning deck

He had this foolish whim

Not because he was stout of heart

But because he could not swim.

Still, “Casabianca” got me to wrestle with substantive issues at a young age. Maybe that’s what educator Ravitch appreciates.

The poem by Lowell, an ardent abolitionist, has appeared dated in the past but it has circled back to relevance. The stanza that Sen. Alexander ignored, to his everlasting shame, used to be part of an Episcopalian hymn. It got dropped in the 1982 hymnal revision because it is so stark and uncompromising:

Once to every man and nation comes the moment to decide,

In the strife of Truth with Falsehood, for the good or evil side;

Some great cause, God’s new Messiah, offering each the bloom or blight,

Parts the goats upon the left hand, and the sheep upon the right,

And the choice goes by forever ‘twixt that darkness and that light.

I remember singing the hymn as a member of the Otey Parish children’s choir in the early 1960s and thinking, “Wow, God really means business.” Much about the church seemed dark to me in those days, including a confessional which had us recite, “We have left undone those things which we ought to have done; And we have done those things which we ought not to have done; And there is no health in us.” God seemed to me to be pissed off all the time, and I’m not surprised that I dropped religion with a feeling of relief when I got to high school. I didn’t return to the church until I was in my forties.

And yet, for all that, these poems are buried deep within me, enforcing a sense of social duty and moral obligation. Doing what is right, I have always assumed, is necessarily hard, and if it weren’t, there would be no virtue in doing it. As I say this, I think of Hester Prynne momentarily imagining that she can jettison the scarlet letter, only to be called back to religion and law by her daughter Pearl throwing a fit.

But enough of me and Ravitch for the moment. Lowell wrote his poem when his nation was grappling with slavery, and as we are once again facing dire threats to the nation, we need Lowell’s reminder to step up. Which principle will prevail, white minority rule or “all men are created equal”?

Like many abolitionists (including Julie Ward Howe in “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”), Lowell resorts to apocalyptic Biblical language. On the one side stand Evil, wrong, and falsehood, on the other right, Truth, and God. Which side are you on, Lowell asks:

Hast thou chosen, O my people, on whose party thou shalt stand,

Ere the Doom from its worn sandals shakes the dust against our land?

Though the cause of Evil prosper, yet ’tis Truth alone is strong,

And, albeit she wander outcast now, I see around her throng

Troops of beautiful, tall angels, to enshield her from all wrong.

While these days it’s generally the Christian right rather than the Christian left that mixes politics with apocalyptic religion, I recognize in Lowell’s concluding stanza my own moral compass:

New occasions teach new duties; Time makes ancient good uncouth;

They must upward still, and onward, who would keep abreast of Truth;

Lo, before us gleam her camp-fires! we ourselves must Pilgrims be,

Launch our Mayflower, and steer boldly through the desperate winter sea,

Nor attempt the Future’s portal with the Past’s blood-rusted key.

In the current battle, those who see a clash of civilizations square off against those who see Trumpism threatening the words inscribed on the Statue of Liberty and our existence as a multicultural democracy. Like Lowell, I believe the moment has come to take sides. No cowering slaves allowed.

One last thought. Despite some very grim images, including a corpse crawling around unburied, the poem isn’t altogether grim. In the opening lines, we see the joy of devoting one’s life to a noble cause. The slave in this stanza is the previously cowering citizen who, feeling an “energy sublime,” bursts full-blossomed into manhood (and, we should add, womanhood):

When a deed is done for Freedom, through the broad earth’s aching breast

Runs a thrill of joy prophetic, trembling on from east to west,

And the slave, where’er he cowers, feels the soul within him climb

To the awful verge of manhood, as the energy sublime

Of a century bursts full-blossomed on the thorny stem of Time.

In short, do what you can as we move towards the election.

And another note: Thanks to Wikipedia, I recently learned the poem provided the title for the NAACP’s Crisis newsletter and that Martin Luther King cited if often. It’s more evidence that we need it today.