Wednesday

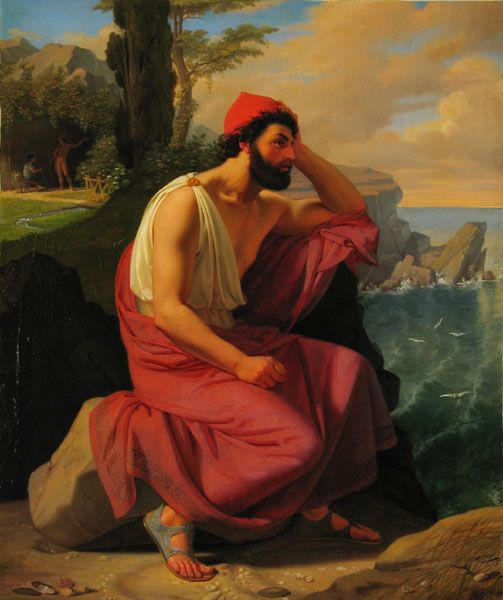

My daughter-in-law Betsy alerted me to an account by a Fulbright professor in Jordan about teaching The Odyssey to a class filled with refugees. Suddenly Dr. Richmond Eustis saw Homer’s epic in an entirely new light. After all, Odysseus is literature’s most famous refugee.

Eustis also says that those Americans who are reacting hysterically to Syrian refugees would do well to revisit the poem.

Before he taught his class, Eustis had an entirely different idea of how he would proceed. Here is what he anticipated:

In teaching the work, I like to focus on depictions of terrain: lush Ogygia, rocky Ithaka, the perilous wilderness of the wine-dark sea. And still smoldering on the shore behind them, the ruins of Troy. There are nymphs and witches, seduction and intrigues, gruesome violence and angry gods. There is an awkward adolescent becoming a man, a clever hero taking vengeance on his enemies, and a crafty wife thwarting the designs of boorish suitors. There is the joyful reunion of a loving, long-parted couple, and the restoration of order to a troubled oikos. The Odyssey is romance and comedy.

And here he is after encountering his students’ responses:

But that’s not how my students in Jordan read it at all. Many of them are Syrian, or Iraqi, or Palestinian refugees. In their written responses to the first three books, much of the class wrote some variation of: “We know this story. We know what it is to be unable to go home, to show up with nothing at the door of strangers and hope they greet us with kindness instead of anger. We know what it’s like to wonder about the fate of family members, caught up in wars that seem to go on forever, and to hope that one day we will see them again.”

Eustis notes that, in a population of eight million, Jordan has one million registered refugees or asylum-seekers from Syria and Iraq, along with another two million Palestinian refugees. And the figures don’t include the many who are in the country without official refugee status.

Eustis became newly appreciative of The Odyssey’s handling of hospitality to strangers:

In its depiction of Odysseus’s journey, The Odyssey is a survey of the Ancient Greek practice of xenia—reciprocal hospitality. But for my students, it depicts the exile’s anxiety in a world in which the principle of xenia is threatened, in which the stranger’s welcome is in doubt. Odysseus asks himself many times about the inhabitants of the unknown islands: “Savages are they, strangers to courtesy? Or gentle folk who know and fear the gods?”

The students, Eustis says,

grasped the principles of xenia quickly. They are simple: when strangers arrive at the door, the host is to offer them food and drink, and perhaps a wash, before even asking who they are. Only after their needs are met may the host ask questions. In turn, the guest is to behave respectfully, show appreciation and not make demands that cannot be met. These rules, my students said, are a lot like the rules their grandparents follow about guests. The Odyssey presents an array of examples of the treatment of strangers. There is windy Nestor, humble Eumaios, graceful Nausikaa, and anthropophagous [cannibalistic] Polyphêmos. The expansive (if slightly tacky) Menelaus gives a retainer a tongue-lashing for being too slow to offer hospitality to Telémakhos and his companions. In The Odyssey, generous hospitality marks the greatness of a ruler.

Polyphêmos the cyclops is, needless to say, a negative example of hospitality. Not everyone welcomes strangers. In fact, there’s a chance that Nausikaa’s father might choose to kill Odysseus, prompting her advice that he approach her mother first. Even in this instance, he must abase himself, covering himself in ashes, to assure everyone he is not a threat. Being a stranger in a strange land can be a dangerous business.

Which is why the epic is relevant to our current handling of the Syrian refugees, which many Republican governors are trying to bar from their states. Eustis makes the connection:

Today, this set of questions from an ancient work has surfaced again in the political debates in the U.S. and the rest of the world: What is the morally appropriate way to respond to a stranger in need, a person from a distant land who arrives on your shore in need of aid and shelter? What obligations do civilized people owe to the destitute stranger in a world aflame with slaughter and destruction? And how are we to think about those who refuse to acknowledge any such obligations?

Eustis obviously doesn’t think much of those who turn their backs. He asks us therefore to put ourselves in the refugees’ shoes:

I can understand why so many of [my students] took special note of Odysseus’ plea to the Phaiákian queen Arêtê in Book VII: “[G]rant me passage to my father land. My home and friends are far. My life is pain.” For many of them the ruins of Troy are still smoldering behind them, their oikos in utter disarray with little hope of putting it right. And now the hope of safe haven vanishes too. There may be no solace for them across the wine-dark sea, which continues to claim victims in many of the same places it did in Homer’s time.

In a CBC radio interview with Eustis and a Syrian refugee who is one of his students (you can listen to it here), we see how important The Odyssey is. Discussing what it is like not to be able to return home, she states that education and literature are her “only salvation.”