Thursday

During my recent visit to Slovenia, I lectured to an American culture class on “The Cultural Foundations of American Economics: Fanatical Puritans, Rapacious Slave Owners, Crazy Pioneers, and Star-Struck Immigrants.” The teacher who will replace me after I retire has prompted me to modify one of my ideas, however. Daniel Yu of Emory University (coincidentally where I earned by own PhD) writes that Robinson Crusoe’s takeover of the island, often held up as an archetype of Puritan capitalism, is more complicated than scholars realize.

In my talk, I wanted the students to understand the American work ethic, which many cultures consider insane. (In some professions,, 60-hour work weeks with one week of vacation are the norm.) Drawing on Max Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, I contended that our insanity traces back to John Calvin’s belief in predestination and was brought to this country by the Mayflower pilgrims.

Calvinists reasoned that, if God is omniscient, then He knows even before we are born whether we will be “elect” souls designed for heaven or damned souls headed in the other direction. We ourselves don’t have any choice in the matter. Though this might seem a prescription for sitting back—after all, if there’s nothing we can do, why sweat it?—the belief had just the opposite effect. The possibility of hellfire so terrified Calvinists that they combed through their lives looking for indications that they were among the elect. Then, being human, they tried to tilt the playing field through worldly achievement. For instance, in a number of Puritan journals one finds people castigating themselves for having slept more than six hours. After all, as Weber puts it, “every hour not spent at work is an hour lost in service to God’s greater glory.”

Benjamin Franklin’s work schedule and, later, Jay Gatsby’s reflect the mentality.

According to J. Paul Hunter, my dissertation director and author of a seminal book about Daniel Defoe (The Reluctant Pilgrim), the Calvinists’ anxiety led to their meticulous journals. If a positive pattern appeared, then they had reason to hope. This journaling evolved into novel writing, where the lives of commoners like Crusoe, Pamela, Tom Jones and Roderick Random suddenly proved of interest. Pilgrim’s Progress functioned as a bridge from journal to novel.

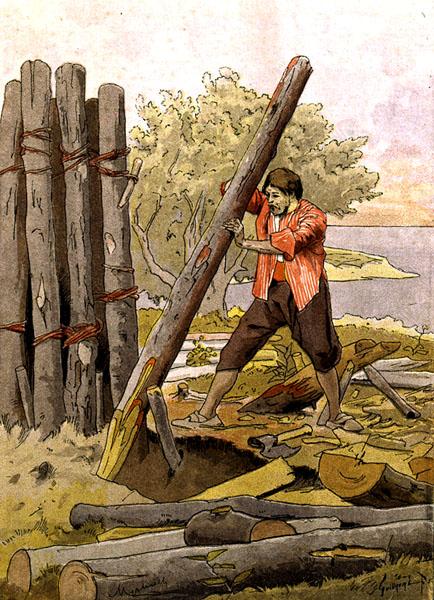

Puritan Crusoe doesn’t colonize his island simply because he desires material possessions. Rather, he is wracked with guilt for having disobeyed his father (by running off to sea) and fears damnation. Therefore he works frantically to prove that he is worthy, and the result is worldly achievement. If Crusoe is Marx’s archetypal capitalist, the reasons lie in spiritual unrest.

In my talk, I acknowledged that few Americans believe in predestination anymore. But the vague sense that we are virtuous if we work hard and sinful if we don’t is a deep part of American culture. Furthermore, there is widespread belief that the poor deserve their misfortune while success is a sign of God’s favor. Many Trump supporters and even Trump himself ascribe to prosperity theology, which has its origins in Calvinism.

Or so I argued in my presentation. Daniel, however, writes in his dissertation that Crusoe isn’t quite the doctrinaire Puritan that I make him out to be, which complicates my argument.

Among other things, Daniel points out that Crusoe has an interesting relationship with tobacco. If Crusoe were really an austere capitalist who pushes aside pleasure, he wouldn’t go for the intoxication associated with the drug. Daniel points out, however, Crusoe believes that self-medicating with rum-soaked tobacco helps him pray authentically, which in turn leads to his recovery. His tobacco intake, in other words, is an integral part of his worship service.

I did what I never had done in all my Life, I kneel’d down and pray’d to God to fulfil the Promise to me, that if I call’d upon him in the Day of Trouble, he would deliver me; after my broken and imperfect Prayer was over, I drunk the Rum in which I had steep’d the Tobacco, which was so strong and rank of the Tobacco, that indeed I could scarce get it down; immediately upon this I went to Bed . . .

Daniel notes 16th century fears that tobacco might supplant the Eucharist and lead to counterfeit religion:

[Some] sixteenth-century writers associated tobacco with idolatry, thereby affirming the legitimacy of Christian conquest. The use of tobacco in ritual to induce a trance state marked native religion as counterfeit since it relied on this indispensable external and material aid. In seventeenth-century England, Anglican authorities continued to decry the use of tobacco as “barbarous and beastly” while also implicating their religious opponents in Europe. In his “Counterblaste to Tobacco,” King James I satirizes Catholic superstition and Puritan self-righteousness in the same breath: “O omnipotent power of Tobacco! And if it could by the smoke thereof chace out devils, as the smoke of Tobias did (which I am sure could smel no stronglier) it would serve for a precious Relicke, both for the superstitious Priests, and the insolent Puritanes, to cast out devils withall.”

Despite these attacks, Crusoe embraces smoking and is particularly proud of the pipe he makes. Nor is this his only pleasure. Daniel points out that he spends long hours, and even days, in non-productive contemplation. In other words, he falls short of the capitalist ideal.

Now, were he to castigate himself up for his inactivity, he would fit my picture of Americans beating themselves up for relaxing rather than working. Daniel, however, believes that people like Crusoe had more investment in non-work than they are given credit for. If that is the case, maybe we can’t blame them entirely for our brutal work ethic.