Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Sunday

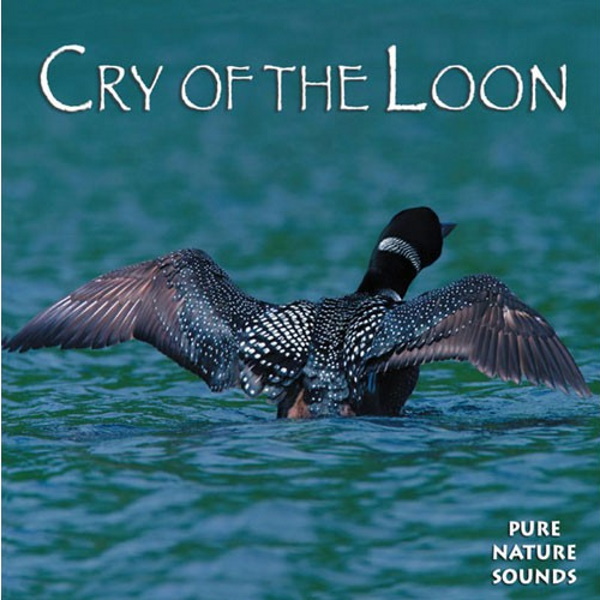

I recently came across a long and fascinating poem by Howard Nemerov in Harold Bloom and Jesse Zuba’s anthology of American Religious Poems. “The Loon’s Cry,” published in The Sewanee Review in 1956 (which, for what it’s worth, was two years after my family moved to Sewanee), seems to be in dialogue with William Wordsworth’s sonnet “The World Is Too Much with Us.”

In that sonnet, Wordsworth is in despair at how capitalist society is so bent on “getting and spending” that “we lay waste our powers.” Nature has become alien to us because “we have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!” Even when we are presented with nature’s unfathomable mysteries, we don’t respond. As Wordsworth puts it,

This Sea that bares her bosom to the moon;

The winds that will be howling at all hours,

And are up-gathered now like sleeping flowers;

For this, for everything, we are out of tune;

It moves us not.

All of which leads the poet to wish he lived in an earlier age when, looking out at sea, one saw not a scientifically explainable natural phenomenon but gods and goddesses:

Great God! I’d rather be

A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn;

So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,

Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn;

Have sight of Proteus rising from the sea;

Or hear old Triton blow his wreathèd horn.

Nemerov, who also has written poems decrying commercialization (for instance, “Boom!”), is having thoughts similar to Wordsworth’s as he walks alone “on a cold evening, summer almost gone.” While struck by the beauty of the scene as the sun goes down and a full moon rises, he worries that he is missing some deeper meaning. As he describes himself at “the fulcrum of two poised immensities” (the sun and the moon), I almost hear him saying (as Yeats says in “The Second Coming”), “Surely some revelation is at hand”:

On a cold evening, summer almost gone,

I walked alone down where the railroad bridge

Divides the river from the estuary.

There was a silence over both the waters,

The river’s concentrated reach, the wide

Diffusion of the delta, marsh and sea,

Which in the distance misted out of sight.As on the seaward side the sun went down,

The river answered with the rising moon,

Full moon, its craters, mountains and still seas

Shining like snow and shadows on the snow.

The balanced silence centered where I stood,

The fulcrum of two poised immensities,

Which offered to be weighed at either hand.

Like Wordsworth, however, he laments that, instead of detecting some otherworldly significance, he is limited to mere nature viewing. “No longer a pagan suckled in a creed outworn” (to quote Wordsworth), he sees only natural science, not theology. He, like Wordsworth, has fallen from “the symboled world” where one found mysteries of meaning, form, and fate/ Signed on the sky”:

But I could think only, red sun, white moon,

This is a natural beauty, it is not

Theology. For I had fallen from

The symboled world, where I in earlier days

Found mysteries of meaning, form, and fate

Signed on the sky, and now stood but between

A swamp of fire and a reflecting rock.

In the past, Nemerov imagines, the “energy in things shone through their shapes” (he uses the image of Japanese lanterns to capture the idea). For instance, one once saw the drama of God’s war with Satan in all things. Now, however, we’ve “traded all those mysteries in for things.” One hears, at this point, Wordsworth chiming in with “a sordid boon”:

I envied those past ages of the world

When, as I thought, the energy in things

Shone through their shapes, when sun and moon no less

Than tree or stone or star or human face

Were seen but as fantastic japanese

Lanterns are seen, sullen or gay colors

And lines revealing the light that they conceal.The world a stage, its people maskers all

In actions largely framed to imitate

God and His Lucifer’s long debate, a trunk

From which, complex and clear, the episodes

Spread out their branches. Each life played a part,

And every part consumed a life, nor dreams

After remained to mock accomplishment.Under the austere power of the scene,

The moon standing balanced against the sun,

I simplified still more, and thought that now

We’d traded all those mysteries in for things,

For essences in things, not understood—

Reality in things! and now we saw

Reality exhausted all their truth.

However, at the very moment the speaker feels we have stripped nature of its mystery by reducing it to thingness—we reduce the world by thinking that the literal is reality and truth—he hears the cry of a loon, which is so primal that it seems invested with transcendent meaning. He feels like he is Adam, “hearing the first loon cry in paradise”:

As answering that thought a loon cried out

Laughter of desolation on the river,

A savage cry, now that the moon went up

And the sun down—yet when I heard him cry

Again, his voice seemed emptied of that sense

Or any other, and Adam I became,

Hearing the first loon cry in paradise.

That haunting cry supersedes our despair at living in a world “that seems too much with us.” With the cry, we are “blessed beyond all that we thought to know”:

For sometimes, when the world is not our home

Nor have we any home elsewhere, but all

Things look to leave us naked, hungry, cold,

We suddenly may seem in paradise

Again, in ignorance and emptiness

Blessed beyond all that we thought to know:

Then on sweet waters echoes the loon’s cry.

The cry puts the world in a new context, seeming to express its contempt at our having reduced reality to “the forms of things.” The loon batters and undermines our seemingly fixed world:

I thought I understood what that cry meant,

That its contempt was for the forms of things,

Their doctrines, which decayed—the nouns of stone

And adjectives of glass—not for the verb

Which surged in power properly eternal

Against the sea wall of the solid world,

Battering and undermining what it built…

What the loon’s cry accomplishes, the poet can accomplish as well. By “respeaking” the world, the poet aims to reawaken us to the world’s mystery, just as the loon does. After hearing the loon’s cry, the speaker is struck by how the moon rises and the stars begin to shine:

And whose respeaking was the poet’s act,

Only and always, in whatever time

Stripped by uncertainty, despair and ruin,

Time readying to die, unable to die

But damned to life again, and the loon’s cry.

And now the sun was sunken in the sea,

The full moon high, and stars began to shine.

This mention of the cold moon leads the poet to think of it as a metaphor for the coldness of our own world, at least to the extent that we have reduced it to thingness. Or in Wordsworth words, to “buying and spending”:

The moon, I thought, might have been such a world

As this one is, till it went cold inside,

Nor any strength of sun could keep its people

Warm in their palaces of glass and stone.

Now all its craters, mountains and still seas,

Shining like snow and shadows on the snow,

Orbit this world in envy and late love.

But in warning what can happen to us, Nemerov is acknowledging that all is not lost. Even though we are faced with a “burning cold,” it is as though the loon’s cry—to which Nemerov adds a distant train whistle—can restore mystery to our world. By means of “arts contemplative” (including poetry) we can read more into things than we thought. They present us with signatures that “leave us not alone/ Even in the thought of death.”

And the stars too? Worlds, as the scholars taught

So long ago? Chaos of beauty, void,

O burning cold, against which we define

Both wretchedness and love. For signatures

In all things are, which leave us not alone

Even in the thought of death, and may by arts

Contemplative be found and named again.The loon again? Or else a whistling train,

Whose far thunders began to shake the bridge.

And it came on, a loud bulk under smoke,

Changing the signals on the bridge, the bright

Rubies and emeralds, rubies and emeralds

Signing the cold night as I turned for home,

Hearing the train cry once more, like a loon.

What began as a cold evening excursion is suddenly filled with “bright/ Rubies and emeralds, rubies and emeralds.” Whereas Wordsworth thought that he had lost forever the vision of “Proteus rising from the sea,” Nemerov assures us that poetry can find and name those things again.

Which is what both Nemerov and Wordsworth do with their poems. In other words, when the world is too much with us—or when we find ourselves standing between sunset and moon rise (“swamp of fire and reflecting rock”)—we can listen to the loon’s cry and to the poet writing about it.

At that point, the world moves from “natural beauty to theology.” Triton blows his wreathèd horn.