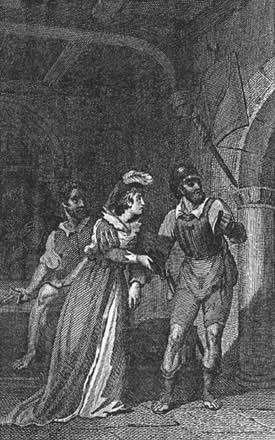

Emily in the Castle of Udolpho

Emily in the Castle of Udolpho

In yesterday’s post I discussed anxious parents and proposed Northanger Abbey as a sane approach to teenage reading (and movie watching and internet using). I elaborate here.

I start first with the reading material in question. Heroine Catherine Moreland and her best friend Isabella Thorpe are enthralled with the novels of Ann Radcliffe. Catherine is working her way through The Mysteries of Udolpho and looking forward to The Italian after that.

Ann Radcliffe was the Stephen King of her day, a writer of Gothics who was the bestselling writer in England and maybe the world. Her novels feature orphaned heroines who are constantly being kidnapped and spirited off by mad monks or tyrannical aunts. They often end up in old castles or convents run by homicidal mother superiors or the dungeons of the Spanish Inquisition until they are finally rescued by handsome young men. Often they encounter apparent supernatural phenomena although these are usually (but not always) revealed to have natural explanations.

Scholars have offered fascinating reasons why young women were so enthralled with Radcliffe’s novels. Perhaps in the heroines’ confinement they saw their own carefully supervised and chaperoned lives and were able to imagine themselves as victims of injustice. Feminist Joanna Russ makes the case that, through kidnapped heroines, young readers could imagine themselves traveling to exotic places. In fact, when Ellena in The Italian is being abducted across the Alps, Radcliffe breaks into encomiums on the beauty of the scenery, with the full moon shining through the pines.

To account for the fascination further, in her book Loving with a Vengeance: Mass Produced Fantasies for Women Tania Modleski identifies paranoia as the key emotion driving the Gothic. The stories are filled with conspiracies and secret plots against the heroine. Modleski says that those people excluded from power (including women in patriarchal society, especially teenage girls) are particularly likely to experience paranoia because, with little control over their lives, their fertile imaginations have no boundaries. They imagine that authority figures have unlimited power.

So parents weren’t entirely wrong when they sensed rebellion in their daughters’ reading selections. But it is one thing to imagine oneself a heroine mistreated by a vicious aunt. It is another to strike out against it.

In Northanger Abbey Austen, an avid Radcliffe lover herself, sees Gothic reading as a harmless pastime. In fact Henry Tilney, the hero who serves as a mentor to Catherine, admits loving Radcliffe novels himself. This surprises her because previously she heard Radcliffe dismissed by the boorish James Thorpe, who functions as a mild version of a Gothic villain. Thorpe dismisses female novelists and purports to like only “manly” novels like The Monk and Tom Jones (which was too bawdy for Austen’s taste).

Tilney, on the other hand, professes to having been so enthralled by Mysteries of Udolpho that he read it non-stop for two days, his hair standing on end the whole time. Real men, in other words, like novels as well as quiche.

But to say that Gothic reading is relatively harmless is not to say that it doesn’t have consequences. Catherine is so taken by Radcliffe’s works that, when she visits the Tilneys at Northanger Abbey, she is prepared to find secret passageways and strange apparitions. Discovering that Tilney’s mother has died, she suspects that General Tilney must either have killed her or locked her up.

She realizes that such suspicions are ridiculous when she is lectured by a scandalized Tilney. She runs from the room in tears, ashamed and embarrassed.

And yet, Catherine isn’t so wrong after all. While the general may not have killed his wife, he is an unkind man who probably made her life miserable. He is capable to a kind of villainy when he discovers (he thinks) that this possible future wife of his son has less money than he thought and sends her away abruptly and rudely—a tremendous breach of etiquette according to the standards of the time.

Austen all but recasts the Gothic plot in an everyday setting. The “villain” James Thorpe at one point carries Catherine away in his carriage despite her pleas that he let her down. Her “friend” Isabella proves to be treacherous and strives to undermine her relationship with Tilney. Catherine, while not an orphan (as Austen pointedly makes clear), must learn how to negotiate on her own the confusing and alien world of Bath, her adult companion Mrs. Allen proving to be useless. When she is sent from Northanger Abbey like a captive heroine whisked away in a carriage, she must rise to the occasion. If we underestimate the difficulty of her challenges, we have forgotten what it was like to be a teenager.

As she learns about the world, Catherine must learn to distinguish between fantasy and fact and grow beyond her childhood love of Gothics. Because she has been raised by parents who have common sense and good values—and who furthermore trust her to do the right thing when she goes off to Bath—she is able to do so.

In fact, the mature Catherine is able to draw on what is best in Gothics. When, in a state of shock, she finds herself expelled from Northanger Abbey, she draws on the example of Udolpho’s Emily and is strong.

To those parents who obsess about what their teenagers are reading or watching, therefore, I offer up the example of Catherine Moreland. Raise your children with a strong sense of self and they will be able to extract what is healthy from fantasy, reject what is not, and evolve into mature, fully functioning adults. They risk remaining childishly paranoid if you neglect them or fail to trust them–which could lead to a discussion of the paranoia rampant in America today.

3 Trackbacks

[…] more here: The Rebellious Thrill of Gothics […]

[…] written in a previous post how Catherine is not entirely wrong in her suspicions of the general. Although innocent of his […]

[…] in the past how young people turn to gothics to process a confusing and threatening reality (see here and here), and the New York Times extends the idea to today’s tabloid culture. Author Carina […]