Sunday

Last Sunday we heard a wonderful passage from the Epistle of James about the danger of the tongue. The brother of Jesus (or so tradition identifies him) is at his metaphorical best as he talks about how the tongue has the potential to set one’s entire life on fire and “is itself set on fire by hell.”

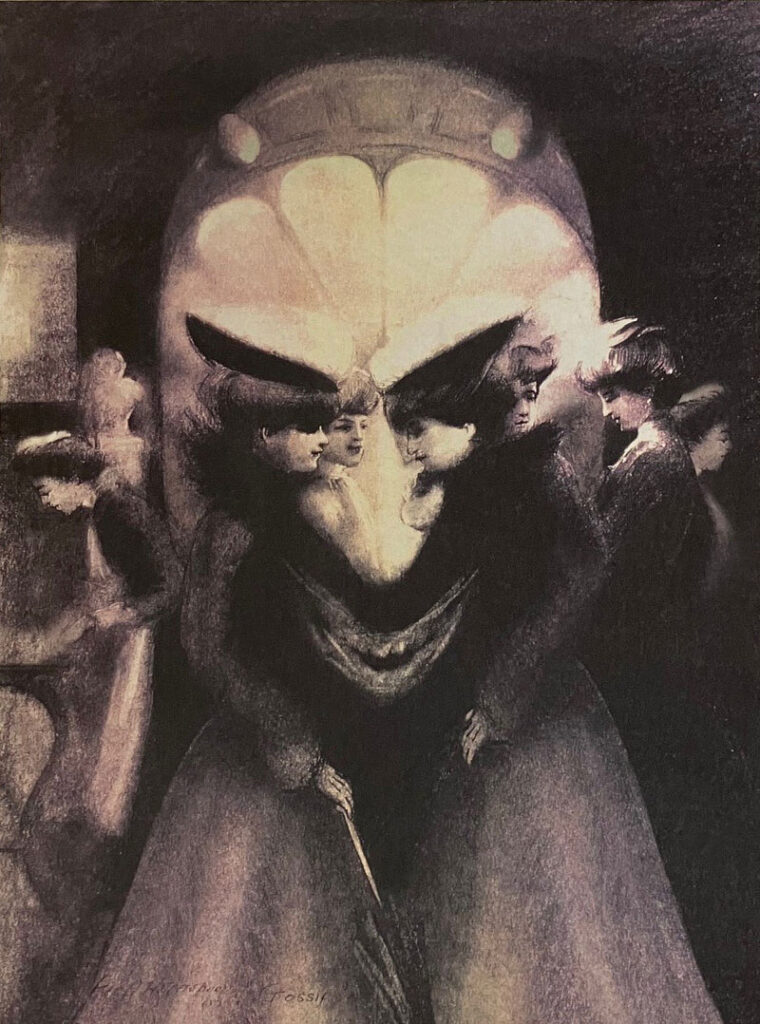

Given the rhetoric we are seeing in the current presidential campaign, some of it leading to dozens of bomb threats in Springfield, Ohio, it is a timely observation. In today’s post I pair the passage with “Scandal,” a poem by the Canadian poet Jean Blewitt (1872-1934)

First, here’s James (3:3-12):

When we put bits into the mouths of horses to make them obey us, we can turn the whole animal. Or take ships as an example. Although they are so large and are driven by strong winds, they are steered by a very small rudder wherever the pilot wants to go. Likewise, the tongue is a small part of the body, but it makes great boasts. Consider what a great forest is set on fire by a small spark. The tongue also is a fire, a world of evil among the parts of the body. It corrupts the whole body, sets the whole course of one’s life on fire, and is itself set on fire by hell.

All kinds of animals, birds, reptiles and sea creatures are being tamed and have been tamed by mankind, but no human being can tame the tongue. It is a restless evil, full of deadly poison.

With the tongue we praise our Lord and Father, and with it we curse human beings, who have been made in God’s likeness. Out of the same mouth come praise and cursing. My brothers and sisters, this should not be. Can both fresh water and salt water flow from the same spring? My brothers and sisters, can a fig tree bear olives, or a grapevine bear figs? Neither can a salt spring produce fresh water.

In short, clean up your act so that only fresh water flows from your lips.

I’m thinking that Blewitt may be channeling the James passage in her own lyric. After all, she too sees hell as the originator of verbal poison. The tragedy, she says, is that such liars may be half believed. Heaven has lent us the breath to speak, so to use it to reflect badly on some white soul is reprehensible.

James would agree.

Scandal

By Jean Blewett

He does the devil’s basest work, no less,

Who deals in calumnies—who throws the mire

On snowy robes whose hem he dare not press

His foul lips to. The pity of it! Liar,

Yet half believed by such as deem the good

Or evil but the outcome of a mood.

That one who, with the breath lent him by Heaven,

Speaks words that on some white soul do reflect,

Is lost to decency, and should be driven

Outside the pale of honest men’s respect.

O slanderer, hell’s imps must say of you:

“He does the work we are ashamed to do!”

Additional thought: This is something that may interest only me, but I have a sense that Sir Philip Sidney, to whom I devote a chapter in my book, may be channeling James when he talks about the power of poetry to do both good and bad:

Nay, truly, though I yield that poesy may not only be abused, but that being abused, by the reason of his sweet charming force, it can do more hurt than any other army of words, yet shall it be so far from concluding, that the abuse shall give reproach to the abused, that, contrariwise, it is a good reason, that whatsoever being abused, doth most harm, being rightly used (and upon the right use each thing receives his title) doth most good. Do we not see skill of physic, the best rampire to our often-assaulted bodies, being abused, teach poison, the most violent destroyer? Doth not knowledge of law, whose end is to even and right all things, being abused, grow the crooked fosterer of horrible injuries? Doth not (to go in the highest) God’s word abused breed heresy, and His name abused become blasphemy?… With a sword thou mayest kill thy father, and with a sword thou mayest defend thy prince and country… (Defence of Poesie, 1580)