Monday – Memorial Day

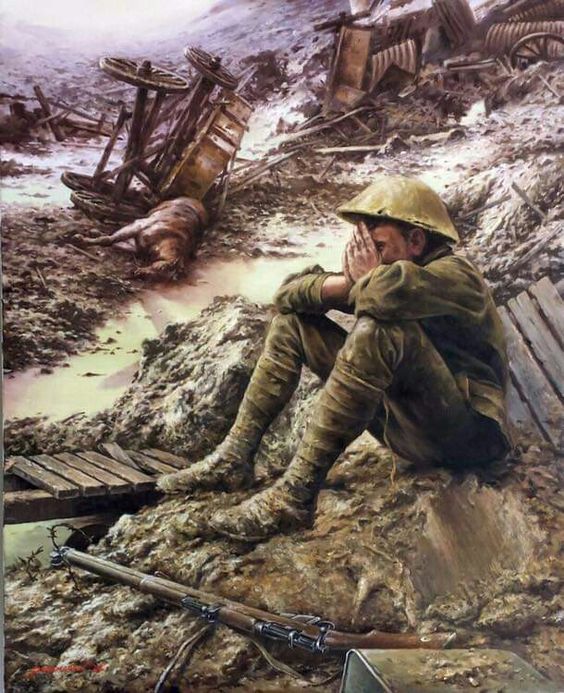

This Memorial Day I turn once again to Wilfred Owen, my favorite anti-war poet. In “The Unreturning,” the speaker longs for his fallen comrades but hears only silence.

The night having “crushed” the day, the poet lies awake watching for his friends, only to learn that “they were all too far, or dumbed, or thralled” so that “never one fared back to me or spoke.”

Just as Owen excoriates those who romanticize war in poems like “Dulce et Decorum Est,” so in this sonnet he castigates those who offer up facile religious consolations. If the dead have gone to heaven, then they are chained there, “gagged by the smothering wing which none unbinds.”

In British poetry, “wing” has religious associations. George Herbert’s famous emblem poem “Easter Wings,” starts in a dark place but then erupts into Resurrection hope, a butterfly emerging out of a caterpillar. Although we begin by “decaying more and more,” come Easter we shall “sing this day thy victories.” The poet confidently concludes, “Affliction shall advance the flight in me.”

In the Gerard Manley Hopkins poem I wrote about last week, the world may be “seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil.” Nevertheless, the poet asserts that the Holy Spirit broods over us until we emerge “with ah! bright wings.”

There is no flight, no emergence of bright wings, in “The Unreturning.” Instead of protecting and nurturing, the wings of the dove smother. Dawn is not a hopeful moment but a “weak-limned” (poorly illuminated) hour when sick men are likely to die.

Owen uses the word “gloaming,” which points to twilight rather than dawn and to the opening lines, where we have seen night hurling the remnants of the day “over cloud-peaks, thunder-walled.” At best, the “indefinite unshapen dawn” is as sad as a half-lit (half drunk) mind.

If God looks after our fallen soldiers, we should not be glib when we invoke this divinity. Shallow belief dishonors the soul-crushing reality of war death. Owen demands that we face up to the silence of “the Dead” before we seek religious comfort. Otherwise, it becomes too easy to engage in future wars.

Suddenly night crushed out the day and hurled

Her remnants over cloud-peaks, thunder-walled.

Then fell a stillness such as harks appalled

When far-gone dead return upon the world.

There watched I for the Dead; but no ghost woke.

Each one whom Life exiled I named and called.

But they were all too far, or dumbed, or thralled;

And never one fared back to me or spoke.

Then peered the indefinite unshapen dawn

With vacant gloaming, sad as half-lit minds,

The weak-limned hour when sick men’s sighs are drained.

And while I wondered on their being withdrawn,

Gagged by the smothering wing which none unbinds,

I dreaded even a heaven with doors so chained.

Further thought: “Unreturning” is a Petrarchan sonnet, but in this one it is the Dead, not the mistress, who rejects the lover. It’s not Owen’s only poem where, with grim irony, he plays death against love. “Greater Love” opens with “English lips are so no red/ As the stained stones kissed by the English dead,” and closes with “Weep, you may weep, for you may touch them not.” The title is from Jesus’s words to his disciples (John 15:13), “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” Yet deep comrade love seems mocked when, as Owen also notes in that poem, “God seems not to care.” As in “Unreturning,” this is not an occasion for religious platitudes.