Monday

Although I’m 70 years old, I’m always learning, and one thing I’ve grasped in a new way over the past six years is that appeasement doesn’t stop bullies. My natural inclination when I encounter disagreement is to make concessions in hopes that the other side will engage in good faith negotiating, but Trump and Putin have made me realize how naïve this is. As authoritarians see it, any concession is a sign of weakness and an invitation to push even more.

This is true as well of anti-abortion crusaders—which is why scaling back or overturning Roe v Wade, as Washington Post columnist Ruth Marcus points out, will be

just the start. For those who believe that abortion is the taking of a human life, allowing it to remain legal in wide swaths of the country is intolerable.

As Marcus sees it, anti-abortionists will start with banning abortion in red states and then in all states. After that, rightwing forces will go after birth control and same sex marriage and who knows what else.

Last week Margaret Atwood wrote in an Atlantic article about composing The Handmaid’s Tale. “I stopped writing it several times,” she reports,

because I considered it too far-fetched. Silly me. Theocratic dictatorships do not lie only in the distant past: There are a number of them on the planet today. What is to prevent the United States from becoming one of them?

Atwood notes that she took some of her inspiration from “17th-century New England Puritan religious tenets and jurisprudence,” which is ironic given that Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito cited a 17th century judge, one Sir Matthew Hale, in his draft opinion overturning Roe. (Hale voiced suspicion of women who charge rape, contended marital rape was an impossibility [since men own their wives, they can’t rape themselves], and sentenced two “witches” to death.) In her article Atwood observes that there are differing religious views on abortion and that, in settling on one, the United States would be imposing a religious rule on the entire country, in violation of the “freedom of religion” clause in the First Amendment:

When does a fertilized human egg become a full human being or person? “Our” traditions—let’s say those of the ancient Greeks, the Romans, the early Christians—have vacillated on this subject. At “conception”? At “heartbeat”? At “quickening?” The hard line of today’s anti-abortion activists is at “conception,” which is now supposed to be the moment at which a cluster of cells becomes “ensouled.” But any such judgment depends on a religious belief—namely, the belief in souls. Not everyone shares such a belief. But all, it appears, now risk being subjected to laws formulated by those who do. That which is a sin within a certain set of religious beliefs is to be made a crime for all.

If America were being true to its Constitution, Atwood says—which is what the self-proclaimed “originalists” on the Supreme Court claim they are–it “ought to be simple”:

If you believe in “ensoulment” at conception, you should not get an abortion, because to do so is a sin within your religion. If you do not so believe, you should not—under the Constitution—be bound by the religious beliefs of others. But should the Alito opinion become the newly settled law, the United States looks to be well on the way to establishing a state religion. Massachusetts had an official religion in the 17th century. In adherence to it, the Puritans hanged Quakers.

Once jurisdictions start policing such matters, Atwood points out, they will unleash chaos. For instance,

it will be very difficult to disprove a false accusation of abortion. The mere fact of a miscarriage, or a claim by a disgruntled former partner, will easily brand you a murderer. Revenge and spite charges will proliferate, as did arraignments for witchcraft 500 years ago.

The Canadian author concludes that if America really wants to “be governed by the laws of the 17th century,” then it “should should take a close look at that century.”

“Is that when you want to live?” she asks.

After reading Atwood’s article, I revisited Handmaid’s Tale, which I’ve taught twice, to see what insights she gives on how a society becomes a Gilead. In flashbacks scattered throughout the novel, handmaid Offred recounts how the current theocratic state came about. A one point, she notes,

Nothing changes instantaneously: in a gradually heating bathtub you’d be boiled to death before you knew it. There were stories in the newspapers, of course, corpses in ditches or the woods, bludgeoned to death or mutilated, interfered with, as they used to say, but they were about other women, and the men who did such things were other men. None of them were the men we knew. The newspaper stories were like dreams to us, bad dreams dreamt by others. How awful, we would say, and they were, but they were awful without being believable. There were too melodramatic, they had a dimension that was not the dimension of our lives.

If one is living in a blue state, the possibility of banned abortion seems far removed. If one is living in a red state, the possibility of a ban on contraception seems far removed. And yet Mitch McConnell has said that, if the Republicans were to regain power, they could well pass a federal ban, and there are Republican legislators (including my home state senator Marsha Blackburn) who want the Supreme Court to revisit privacy laws allowing birth control. There are also legislators talking about forbidding women to travel out of state to get abortions and tracking the health records and internet searches of those who are pregnant. Yet we find ways to shrug off these concerns. As Offred observes,

We were the people who were not in the papers. We lived in the blank white spaces at the edges of print. It gave us more freedom.

Later in the novel, the United States experiences a military coup following an unspecified national catastrophe. In spite of this, the army reassures the public:

It was after the catastrophe, when they shot the president and machine-gunned the Congress and the army declared a state of emergency. They blamed it on the Islamic fanatics, at the time.

Keep calm, they said on television. Everything is under control.

I was stunned. Everyone was, I know that. It was hard to believe. The entire government, gone like that. How did they get in, how did it happen?

Even after the new leaders suspend the Constitution, there’s a muted response:

They said [the suspension] would be temporary. There wasn’t even any rioting in the streets. People stayed home at night, watching television, looking for some direction. There wasn’t even an enemy you could put your hand on.

Looking back, the naïve June reports that her more worldly-wise friend Moira was more alert to the danger:

You wait, she said. They’ve been building up to this. It’s you and me gainst the wall, baby.

Atwood’s plot may have appeared far-fetched in 1985 but not now, given that we barely escaped our own coup on January 6, 2021. And unlike the coup in the novel where Muslim terrorists provide the rationale, Trump supporters have been openly taking credit for ours. We learn from Trump flunky Peter Navarro that the coup plan had a name–“The Green Bay Sweep”—and from Trump lawyer John Eastman’s e-mails about attempts to convince Pennsylvania politicians to come up with “cover” (fraudulent voting accusations) so that GOP fake electors could vote for Trump. There were also plans, pending anticipated disturbances following an election overthrow, to declare martial law. Several in the GOP were very open about it.

One would think that all this would be hot enough to get us to leap out of the bathtub. And yet, once again, many Americans are pushing the danger aside, telling themselves that “everything is under control.”

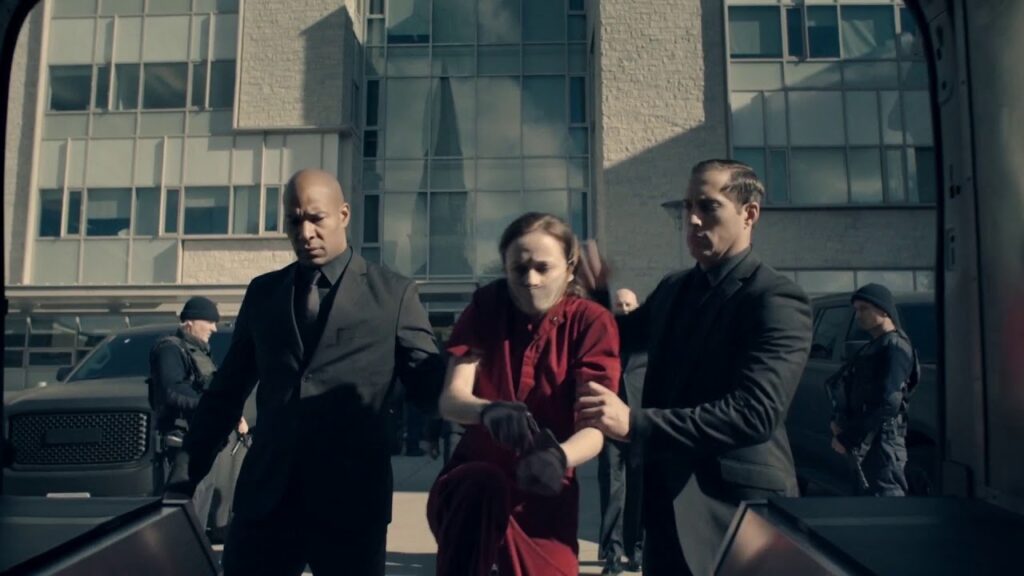

So now there’s talk in some states, if Roe v Wade is overturned, about not allowing pregnant women to cross state lines to get abortions. In the novel, meanwhile, June and her husband and daughter attempt to flee to Canada. June sees her husband shot and her daughter kidnapped, and she herself is turned into a breeding machine.

Could Christian fascists triumph here? If Roe v Wade is overturned, they’ll have the wind in their sails.

Reader response: When I first responded to Alito’s draft ruling, I received the following response from reader Matthew Currie, which smartly lays out what may be coming:

One of the things I find most scary about this already scary future is that many on the anti-choice side have announced that their next target will be the Griswold Vs. Connecticut decision, with an aim toward outlawing the protection of birth control, ostensibly on the ground that the IUD creates an abortion. And of course, with the privacy issue may go gay marriage, and racial equality. Of course the people going against Griswold assure us they don’t want to ban all birth control, and don’t want to do this or that, but they are making it possible.

A woman gets an IUD at a time when she is not pregnant. It is a procedure performed on the single individual who, up until now, has been considered to own her own reproductive apparatus. In fact a person could get an an IUD and die a virgin. What it does is to make the uterus unreceptive to a zygote. If the IUD is banned, it will, not sort of, not virtually, but literally, mean that a woman is not allowed to control a part of her own body. The idea that an IUD is an abortion requires that a fertilized egg not only has the rights of a human being to live, but the right to find a home, and that this right is retroactive – that a person must provide that possibility before the “person” exists.

The banning of any form of birth control is, I think, an abomination, but singling out the IUD adds a fearsome dimension, because it truly declares that at any time, any place, any age, and any circumstance, a woman’s uterus is government property. We can, of course, assume that the ignorant idiots in charge of this will not realize or take advantage of the existential change this entails, but our faith in human nature and moderation is rarely met. If you can tell a woman what procedures she may perform on her uterus, why can’t you tell her what else she must do with it, when she must, with whom she must or must not?

You could argue, I think, that banning the IUD, if not any birth control, is a subset of eugenics.