Tuesday

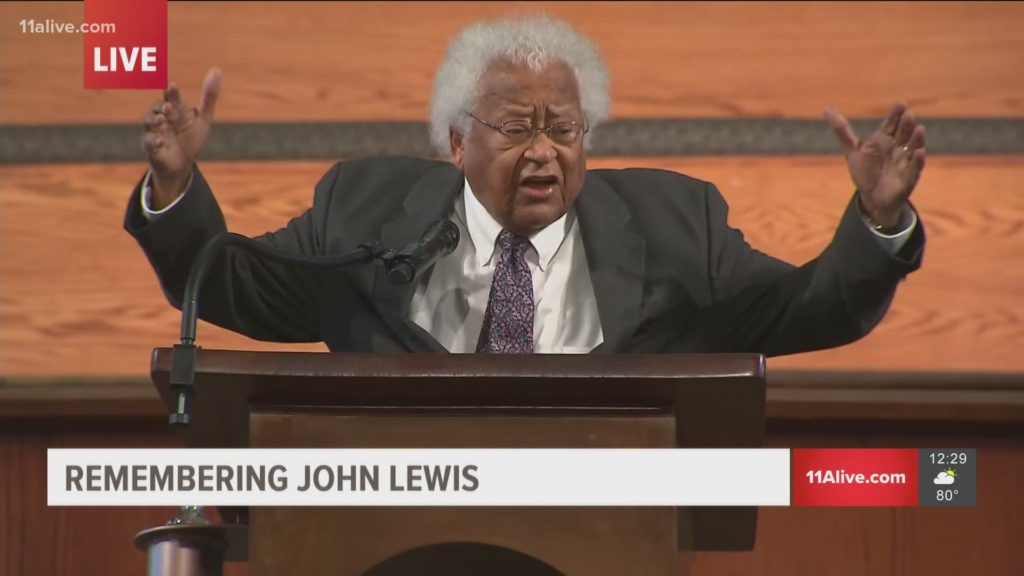

Poetry steps up when other language falls short, which is why we often encounter it at funerals. Activist James Lawson, John Lewis’s mentor, particularly caught my attention when he read a Czeslaw Milosz poem last week. It helped me understand why Lawson is one of the greatest trainers of social activists in American history.

Let me first mention the other poems. I heard two passages from Shakespeare (one quoted twice); Lewis’s favorite poem “Invictus” (which I reflected upon recently); and Langston Hughes’s “I Dream a World,” which inspired Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

George W. Bush was one of two borrowing from Horatio’s farewell to Hamlet:

And flights of angels sing thee to thy rest!

Unlike Hamlet, however, Lewis died in peace, believing in his fellow citizens and content to pass the torch to the next generation. He responded to the rottenness in the state with unflinching love. In any event, it’s a lovely farewell.

Ebenezer Baptist Church pastor Raphael Gamaliel Warnock turned to Juliet’s awe and wonder at her love for Romeo to capture his own reverence for Lewis:

…and, when he shall die,

Take him and cut him out in little stars,

And he will make the face of heaven so fine

That all the world will be in love with night

And pay no worship to the garish sun.

If we see the “garish sun” as established authorities, then it seems right to celebrate this advocate for “good trouble” as a figure of the night.

I can’t remember who read “I Dream a World,” but it was appropriate for a man who, as Barack Obama put it, often believed in us more than we believed in ourselves:

I dream a world where man

No other man will scorn,

Where love will bless the earth

And peace its paths adorn

I dream a world where all

Will know sweet freedom's way,

Where greed no longer saps the soul

Nor avarice blights our day.

A world I dream where black or white,

Whatever race you be,

Will share the bounties of the earth

And every man is free,

Where wretchedness will hang its head

And joy, like a pearl,

Attends the needs of all mankind-

Of such I dream, my world!

But back to Lawson, who read both “Invictus” and Milosz’s “Meaning.” As he read the first poem, Lawson may have remembered the “bludgeonings” he himself endured and witnessed, while always advocating a non-violent response (“My head is bloody and unbowed”).

“Meaning” is considerably more complex:

When I die, I will see the lining of the world.

The other side, beyond bird, mountain, sunset.

The true meaning, ready to be decoded

What never added up will add Up,

What was incomprehensible will be comprehended

--And if there is no lining to the world?

If a thrush on a branch is not a sign,

But just a thrush on the branch? If night and day

Make no sense following each other?

And on this earth there is nothing except this earth?

--Even if that is so, there will remain

A word wakened by lips that perish,

A tireless messenger who runs and runs

Through interstellar fields, through the revolving galaxies,

And calls out, protests, screams.

First, this is a great poem to read at the funeral of a lifelong warrior for justice. Through the first five lines, it’s as though Lewis finds life’s work confirmed with his death, which is how many many witnessing the funeral saw it.

Milosz, however, is famous for never allowing assertions to go unquestioned, including his own. His Nobel acceptance speech is a masterclass in simultaneously declaring truths and challenging them. In this poem, he switches from confidence the world has transcendent meaning to the possibility it does not. Lewis, like Martin Luther King, might have believed the arc of history bends towards justice—their struggle occurred within the context of that faith—but what if it doesn’t? What if “on this earth there is nothing except this earth?”

Lawson knows that, whatever confidence social activists exude in public, privately they have their moments of doubt. He undoubtedly saw such doubts up close countless times. Milosz’s lesson for social activists is that they may be able to do no more than call out, protest, scream with their perishable lips. The downward trajectory from calling out to screaming suggests that the intended audiences are not listening.

People like Lewis—and for that matter, poets—are like the “tireless messenger who runs and runs/ Through interstellar fields, through the revolving galaxies.” Maybe no “true meaning” exists, and yet the poem somehow endows such activity with cosmic significance. Through human striving, meaning is made.

Love may be an essential part of the lining of the world, as John Lewis professed, or it may not. What’s important is that, when all is said and done, Lewis tirelessly called out the word with lips that have now perished. In doing so, he awakened others and changed history.

Further thought: Milosz’s vision of a messenger who “calls out, protests, screams” brings to mind a famous passage from In Memoriam where Tennyson grapples with whether a higher meaning exists within the universe. Although he will come around to a more positive vision, at this stage Tennyson is racked with doubt:

Oh, yet we trust that somehow good

Will be the final end of ill,

To pangs of nature, sins of will,

Defects of doubt, and taints of blood;

That nothing walks with aimless feet;

That not one life shall be destroy'd,

Or cast as rubbish to the void,

When God hath made the pile complete;

That not a worm is cloven in vain;

That not a moth with vain desire

Is shrivell'd in a fruitless fire,

Or but subserves another's gain.

Behold, we know not anything;

I can but trust that good shall fall

At last—far off—at last, to all,

And every winter change to spring.

So runs my dream: but what am I?

An infant crying in the night:

An infant crying for the light:

And with no language but a cry.