Wednesday

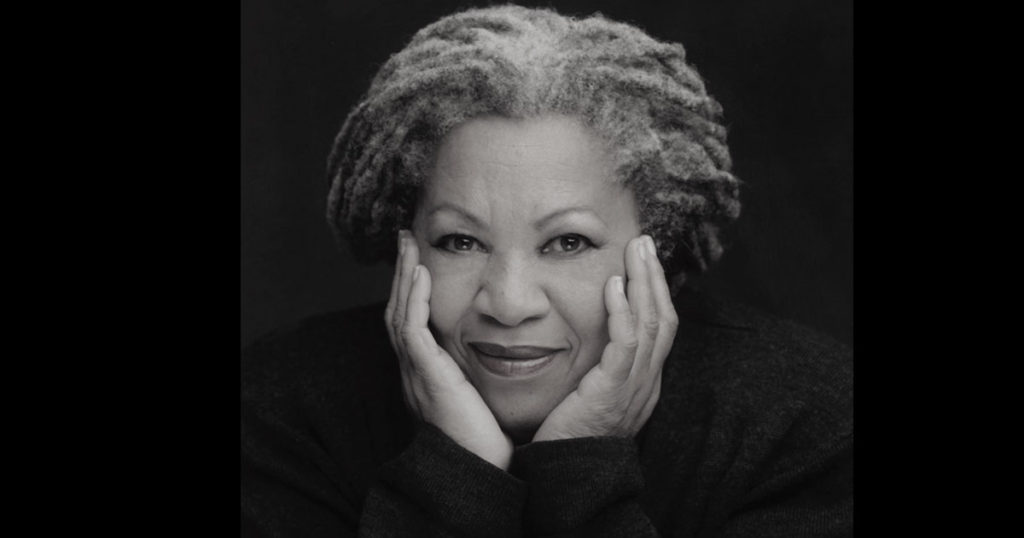

“National treasure” is an overused metaphor, but it is entirely warranted in the case of the late Toni Morrison. Bluest Eye showed us how we internalize race prejudice, Sula helped us understand “bad girls,” Song of Solomon shaped Barack Obama, Tar Baby exposed the emptiness of the middle class promise, Beloved explored the impact of trauma on race victims. In my opinion, this last novel contends with Huckleberry Finn and The Great Gatsby for “the great American novel.” We owe her a tremendous amount.

MSNBC’s Ari Melber reminded me of the following passage (from Morrison’s Nobel speech) of how people systematically loot language, robbing it of its nuance and complexity. Rather than use it as a midwife to truth, they employ it for “menace and subjugation.” At times echoing George Orwell’s Politics and the English Language, Morrison mentions “estrangement of minorities” as one of the ways that language gets looted. Trump loots when he characterizes Central Americans immigrants as “rapists and murderers” participating in an “invasion”:

The systematic looting of language can be recognized by the tendency of its users to forgo its nuanced, complex, mid-wifery properties for menace and subjugation. Oppressive language does more than represent violence; it is violence; does more than represent the limits of knowledge; it limits knowledge. Whether it is obscuring state language or the faux-language of mindless media; whether it is the proud but calcified language of the academy or the commodity driven language of science; whether it is the malign language of law-without-ethics, or language designed for the estrangement of minorities, hiding its racist plunder in its literary cheek – it must be rejected, altered and exposed. It is the language that drinks blood, laps vulnerabilities, tucks its fascist boots under crinolines of respectability and patriotism as it moves relentlessly toward the bottom line and the bottomed-out mind. Sexist language, racist language, theistic language – all are typical of the policing languages of mastery, and cannot, do not permit new knowledge or encourage the mutual exchange of ideas.

Trump doesn’t care much for literary cheek or respectability, but he does tuck his “fascist boots” under the crinolines of patriotism. His language drinks blood and laps vulnerabilities.

I’ve read ten of Morrison’s 11 novels (all but Jazz) and over the years taught three of them (Bluest Eye, Song of Solomon, and Beloved). I can therefore testify that the mutual exchange of ideas is vital for her. Her novels open up the full complexity of the human experience and anyone attempting to shut down that complexity gets her full attention.

Take the figure of Guitar in Song of Solomon, for instance. In the grip of a radical ideology that insists that an innocent white be killed for every innocent black murdered by racists, he loses his humanity and turns on his best friend. That friend, meanwhile, is trapped in his own blindness but saves himself by undergoing a roots quest that liberates his mind and enables him to see the fullness that is other people.

Morrison pays special attention to those who attempt to exclude others. In Paradise, for instance, she imagines a utopia set up by freed slaves who somehow manage to live a life independent of the Jim Crow south. As wonderful as it is, however, Paradise pays a price for its exclusionary policies and by the end is engaging in its own bloodletting.

Morrison often dwells on the tension between assimilation and separatism. If African Americans assimilate too thoroughly, they lose much of their richness (witness the slumlord Macon Dead in Song of Solomon), but if they hold themselves separate, a kind of corruption sets in. This essential truth applies not only to African Americans but to all Americans. An intermingling that honors difference may be our most difficult challenge but it is the key to a vibrant society.

I conclude with Pilate’s dying words in Song of Solomon because it reveals Morrison’s own large heart:

I wish I’d a knowed more people. I would of loved ’em all. If I’d a knowed more, I would a loved more.

Many of Morrison’s characters have become a permanent part of my life. Her love of language and her love of life created them. She understood America as few people have.