Spiritual Sunday

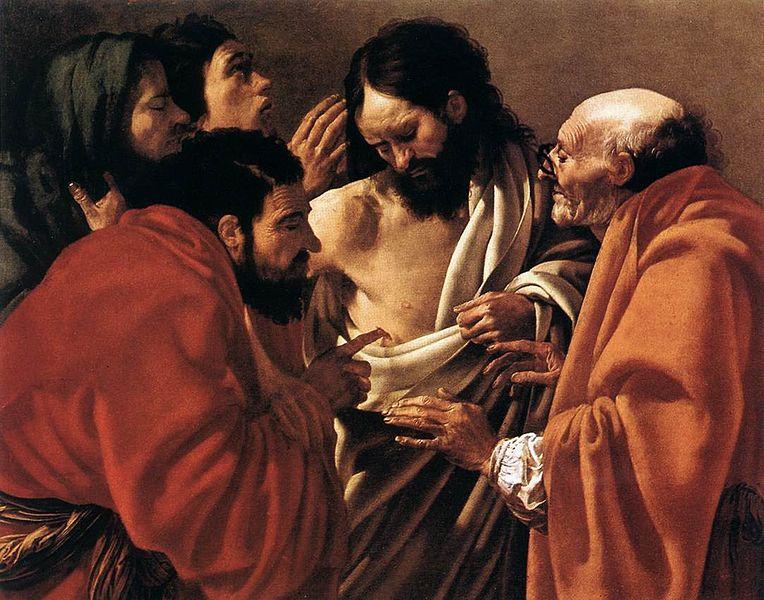

Today’s lectionary reading is the story of Doubting Thomas, about which I’ve blogged a couple of times in the past. Once I posted a fine poem by Welsh poet and Anglican clergyman R. S. Thomas and twice (here and here) I’ve turned to my former colleague Dana Greene, whose biography on Denise Levertov discusses the importance of the Thomas story to a poet wrestling with her own doubts.

In Dana’s post on Levertov’s “St. Thomas Didymus,” however, she only quotes part of the poem. We see her portrayal of Thomas’ moving breakthrough but aren’t show his previous history of doubt. As Levertov tells it in the first part of the poem, Thomas’ doubts go back to an incident where a father of a demon-possessed boy comes to Jesus for healing (Mark 9:17-29). Here’s the story:

A man in the crowd answered, “Teacher, I brought you my son, who is possessed by a spirit that has robbed him of speech. Whenever it seizes him, it throws him to the ground. He foams at the mouth, gnashes his teeth and becomes rigid. I asked your disciples to drive out the spirit, but they could not.”

“You unbelieving generation,” Jesus replied, “how long shall I stay with you? How long shall I put up with you? Bring the boy to me.”

So they brought him. When the spirit saw Jesus, it immediately threw the boy into a convulsion. He fell to the ground and rolled around, foaming at the mouth.

Jesus asked the boy’s father, “How long has he been like this?”

“From childhood,” he answered. “It has often thrown him into fire or water to kill him. But if you can do anything, take pity on us and help us.”

“‘If you can’?” said Jesus. “Everything is possible for one who believes.”

Immediately the boy’s father exclaimed, “I do believe; help me overcome my unbelief!”

When Jesus saw that a crowd was running to the scene, he rebuked the impure spirit.“You deaf and mute spirit,” he said, “I command you, come out of him and never enter him again.”

The spirit shrieked, convulsed him violently and came out. The boy looked so much like a corpse that many said, “He’s dead.” But Jesus took him by the hand and lifted him to his feet, and he stood up.

After Jesus had gone indoors, his disciples asked him privately, “Why couldn’t we drive it out?”

He replied, “This kind can come out only by prayer.”

According to Daniel Clendenin, who posts today on Levertov’s poem in his superb blog “Journey with Jesus,” Levertov takes full advantage of the fact that Thomas’s names mean “the twin,” both the Greek Didymus and the Aramaic T’omas. The Thomas in the poem says that he feels closer to the father of the boy than to “the twin of my birth.” He is responding to the fact that this father is confronted by the unfairness of the world—the suffering of an innocent child—so that his

entire being

had knotted itself

into the one tightdrawn question,

Why…

No wonder that he finds it hard to believe. No wonder that he asks Jesus to “help me overcome my unbelief!”

Despite the healing of the child, Levertov’s Thomas still has his doubt as the father’s words linger:

What I retained

was the flash of kinship.

Despite

all that I witnessed,

his question remained

my question, throbbed like a stealthy cancer,

known

only to doctor and patient. To others

I seemed well enough

With this magnificent lead-up, Thomas’s revelation is all the more moving. The tight knot of doubt miraculously unravels so that he experiences

light, light streaming

into me, over me, filling the room

as I had lived till then

in a cold cave, and now

coming forth for the first time,

the knot that bound me unraveling…

Here’s the poem in its entirety:

St. Thomas Didymus

By Denise Levertov

In the hot street at noon I saw him

a small man

gray but vivid, standing forth

beyond the crowd’s buzzing

holding in desperate grip his shaking

teethgnashing son,

and thought him my brother.

I heard him cry out, weeping and speak

those words,

Lord, I believe, help thou

mine unbelief,

and knew him

my twin:

a man whose entire being

had knotted itself

into the one tightdrawn question,

Why,

why has this child lost his childhood in suffering,

why is this child who will soon be a man

tormented, torn, twisted?

Why is he cruelly punished

who has done nothing except be born?

The twin of my birth

was not so close

as that man I heard

say what my heart

sighed with each beat, my breath silently

cried in and out,

in and out.

After the healing,

he, with his wondering

newly peaceful boy, receded;

no one

dwells on the gratitude, the astonished joy,

the swift

acceptance and forgetting.

I did not follow

to see their changed lives.

What I retained

was the flash of kinship.

Despite

all that I witnessed,

his question remained

my question, throbbed like a stealthy cancer,

known

only to doctor and patient. To others

I seemed well enough.

So it was

that after Golgotha

my spirit in secret

lurched in the same convulsed writhings

that tore that child

before he was healed.

And after the empty tomb

when they told me that He lived, had spoken to Magdalen,

told me

that though He had passed through the door like a ghost

He had breathed on them

the breath of a living man –

even then

when hope tried with a flutter of wings

to lift me –

still, alone with myself,

my heavy cry was the same: Lord

I believe,

help thou mine unbelief.

I needed

blood to tell me the truth,

the touch

of blood. Even

my sight of the dark crust of it

round the nailholes

didn’t thrust its meaning all the way through

to that manifold knot in me

that willed to possess all knowledge,

refusing to loosen

unless that insistence won

the battle I fought with life

But when my hand

led by His hand’s firm clasp

entered the unhealed wound,

my fingers encountering

rib-bone and pulsing heat,

what I felt was not

scalding pain, shame for my

obstinate need,

but light, light streaming

into me, over me, filling the room

as I had lived till then

in a cold cave, and now

coming forth for the first time,

the knot that bound me unravelling,

I witnessed

all things quicken to color, to form,

my question

not answered but given

its part

in a vast unfolding design lit

by a risen sun.