Monday

The New York Review of Books recently had an article about a judge who used a Naomi Shahib Nye poem to protest a Trump Education Department attack against transgender students. As the judge anticipated, the poem made his point more powerfully than legal language could have done.

In May, 2016, the Obama administration invoked Title IX and ordered America’s schools to allow trans students to use the bathroom corresponding to their chosen gender. Here’s what happened when Gavin Grimm started using the boys’ room in a Gloucester Country, Virginia high school:

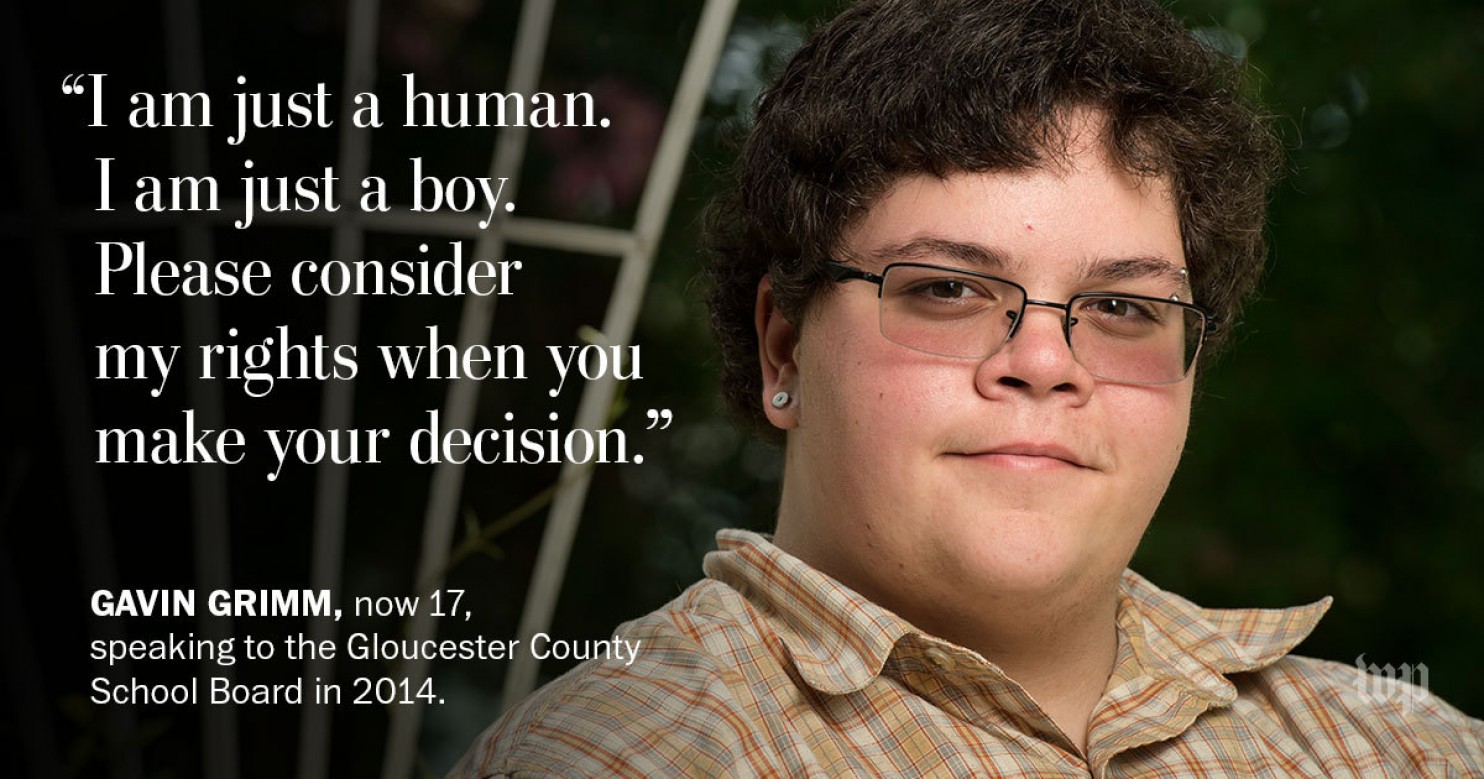

None of the other students objected, but when some adults in the community learned that Gavin was using the boys’ room, they demanded that the school board step in. At a school board meeting, Gavin, still only fifteen, told the board that, “all I want is to be a normal child and use the restroom in peace and I have had no problems from students to do that—only from adults…. I did not ask to be this way, and it’s one of the most difficult things anyone can face.” He insisted, “I am just a human being. I am just a boy.”

The school board rejected his plea, and barred him from using the boys’ room, relegating him to a stigmatizing single-stall restroom that no one else used. Gavin sued and, represented by the ACLU (where I [David Cole] am the National Legal Director), won. The Fourth Circuit, relying on a guidance document issued by the Department of Education under President Obama, ruled that excluding Gavin from the boys’ restroom because he was transgender was sex discrimination in violation of Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972, which covers all schools that receive federal assistance. The court ordered the school board to allow Gavin to resume using the boys’ restroom. But the school board appealed. The Supreme Court stayed the order pending the appeal, and Gavin continued to be barred from the boys’ bathroom. After taking office, the Trump administration revoked the Department of Education guidance document calling for equal treatment of transgender students, upon which the court of appeals had relied, and in light of the revocation of the guidance, on March 6, the Supreme Court vacated the decision and returned the case to the court of appeals.

Cole points out Gavin’s courage throughout the affair:

The mere decision to come out to one’s parents as transgender requires tremendous bravery in a world that still too often dismisses individuals who are transgender as somehow alien. To come out to one’s principal, as Gavin did as a sophomore, demands still greater courage. To speak up in a public school board hearing, and then to file a federal lawsuit, calls for yet greater reserves. Gavin not only pursued his rights to the end, but did so with the utmost grace. Simply by doing so, he has educated a generation about the plight, and the dignity, of those who are transgender.

Judge Andre Davis recognized the courage and, while forced to join the court’s decision to lift the injunction, nevertheless felt that Gavin’s courage should be recognized. Cole quotes from his opinion:

The brief but eloquent opinion deserves to be read in full. Judge Davis compared Gavin to Dred Scott, Fred Korematsu, Linda Brown, Jim Obergefell, and others who had “refused to accept quietly the injustices that were perpetuated against them.”

Gavin’s case, Judge Davis maintained, “is about much more than bathrooms… It’s about protecting the rights of transgender people in public spaces and not forcing them to exist on the margins. It’s about … the simple recognition of their humanity.” By standing up for that principle, Judge Davis continued, Gavin “takes his place among other modern-day human rights leaders who strive to ensure that, one day, equality will prevail.”

At the opinion’s close, Judge Davis turned to poetry to capture Gavin’s bravery. Borrowing from Nye’s poem, “Famous,” he explained that Gavin is “famous,” not in the Hollywood sense of celebrity, but in Nye’s sense, because “[he] never forgot what [he] could do.”

“Famous” operates through a series of contrasts, and one has to think through each of them in applying them to Gavin. Here it is:

Famous

By Naomi Shihab Nye

The river is famous to the fish.

The loud voice is famous to silence,

which knew it would inherit the earth

before anybody said so.

The cat sleeping on the fence is famous to the birds

watching him from the birdhouse.

The tear is famous, briefly, to the cheek.

The idea you carry close to your bosom

is famous to your bosom.

The boot is famous to the earth,

more famous than the dress shoe,

which is famous only to floors.

The bent photograph is famous to the one who carries it

and not at all famous to the one who is pictured.

I want to be famous to shuffling men

who smile while crossing streets,

sticky children in grocery lines,

famous as the one who smiled back.

I want to be famous in the way a pulley is famous,

or a buttonhole, not because it did anything spectacular,

but because it never forgot what it could do.

The poem quietly but insistently gets at the core of Gavin’s heroism. In the first stanza Gavin would be the fish, necessarily aware of his environment as others are not. In the second he is the loud voice that disturbs the silence of a status quo that is confident it will prevail.

The situation becomes more precarious in the third stanza. While cisgender people, like the cat, can afford to sleep comfortably on the fence, potential victims must always be on the lookout. Privilege means that you don’t have to worry about getting eaten.

It makes sense, therefore, that the next two images are of suffering and secrets: even though invisible to others, Gavin’s tears would be known to his cheek and his bosom secrets to his bosom. The bent photograph also fits in this category, a longing carried around but hidden.

It becomes increasingly clear that Nye is talking about the poor and the oppressed in the subsequent stanzas, and we move from potential conflict to support. The working class boot may not be a dress shoe but it finds a home in the earth. Nye wants to be such a home, smiling a smile of comradeship to shuffling men and to children that others find irritating. Maybe that’s why she invokes two unglamorous models for herself in the final stanza.

With a pulley, as poet George Herbert knew, one goes low to pull others up. The poet accomplishes this by smiling at people that others ignore. Button holes, meanwhile, don’t insist on themselves but accommodate themselves to the needs of others. The pulley is famous to that which is pulled up and the button hole to the button. Both are essential but unnoticed, the first an indirect support (the rope gets all the publicity), the second an absent presence.

Gavin, a fish noticing a river invisible to others, became a loud voice, disturbing the silence. He thereby woke up the cats, with all the potential danger they represent. Yet by going low, revealing himself as “deviant,” he lifted up others. Their unbuttoned clothing could find closure.

Gavin knew what he could do and he did it.

As a result, he may well become famous as the other civil rights cases mentioned by the Judge Davis became famous: fugitive slave Dred Scott, Japanese-American interned activist Fred Korematsu, segregation opponent Linda Brown (v Board of Education), and gay marriage’s Jim Obergefell. Those who become known as law cases usually do not set out to call attention to themselves. They just want live like everyone else.

Previous Posts on Naomi Shihab Nye