Tuesday

I don’t often read The National Review but a recent Kevin Williamson article looking at Donald Trump through the eyes of David Mamet’s play Glengarry Glenn Ross has caught my eye. Williamson says that Trump, like the competing realtors in the play, is a wannabe alpha dog.

The play is about the cutthroat world of real estate and makes such liberal use of the “F” word that the original cast (this according to Williamson) referred to it as Death of a F***ing Salesman. I can still remember where I was when I first read the play’s scorching dialogue.

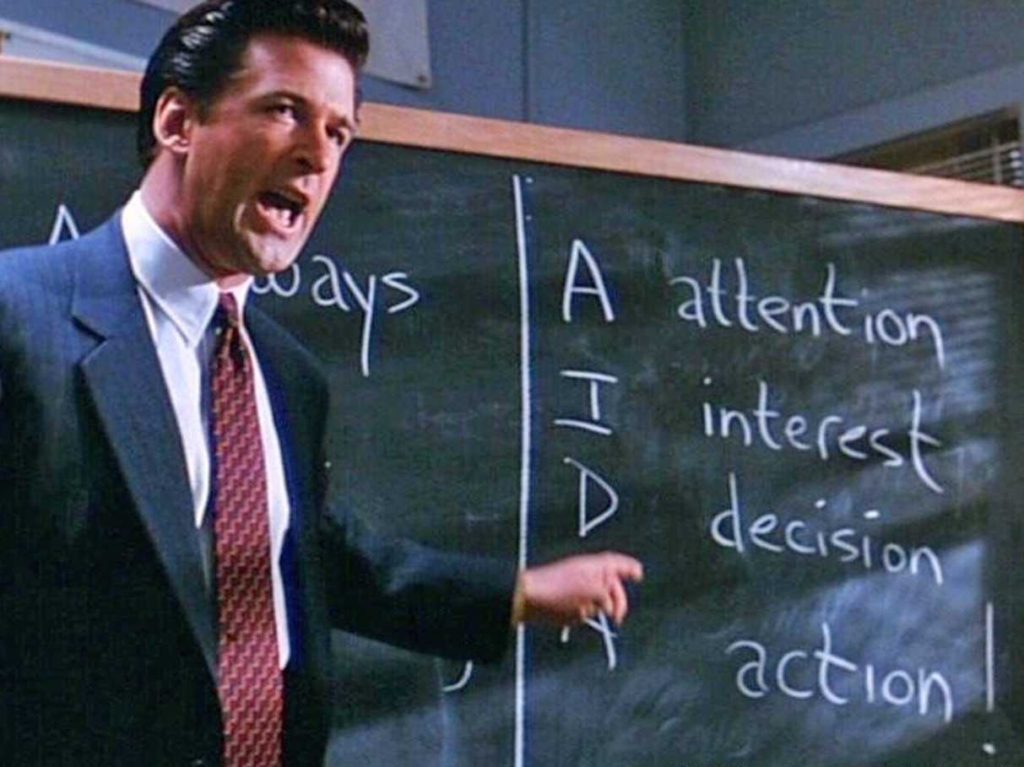

To me, the play is a searing exposé of soulless capitalism and, as such, a worthy successor to Arthur Miller’s play. Williamson notes, however, that certain fans of the play—or rather, of the film—love it, not because it exposes capitalism but because they fantasize being winners who lord it over losers. They want to be Blake, played in the film by Alex Baldwin, who delivers an explosive speech:

As you all know first prize is a Cadillac El Dorado. Anyone wanna see second prize? Second prize is a set of steak knives. Third prize is you’re fired.

And further on, when someone asks his name:

Fuck you! That’s my name! You know why, mister? You drove a Hyundai to get here. I drove an eighty-thousand dollar BMW. THAT’S my name. And your name is you’re wanting. You can’t play in the man’s game, you can’t close them – go home and tell your wife your troubles. Because only one thing counts in this life: Get them to sign on the line which is dotted. You hear me, you fucking faggots? A-B-C. A-Always, B-Be, C-Closing. Always be closing.

And finally:

You see this watch? You see this watch? That watch costs more than your car. I made $970,000 last year. How much’d you make? You see, pal, that’s who I am, and you’re nothing. Nice guy? I don’t give a shit. Good father? Fuck you! Go home and play with your kids. You wanna work here – close! You think this is abuse? You think this is abuse, you cocksucker? You can’t take this, how can you take the abuse you get on a sit? You don’t like it, leave. I can go out there tonight with the materials you’ve got and make myself $15,000. Tonight! In two hours! Can you? Can YOU? Go and do likewise. A-I-D-A. Get mad you son of a bitches, get mad. You want to know what it takes to sell real estate? It takes BRASS BALLS to sell real estate. Go and do likewise, gents. Money’s out there. You pick it up, it’s yours. You don’t, I got no sympathy for you. You wanna go out on those sits tonight and close, CLOSE. It’s yours. If not, you’re gonna be shining my shoes. And you know what you’ll be saying – a bunch of losers sittin’ around in a bar. ‘Oh yeah. I used to be a salesman. It’s a tough racket.’

Williamson points out that Blake doesn’t have the same prominence in the play that he does in the film. The filmmakers wanted to create a larger-than-life alpha dog, which negates some of the power of the play, where the corporate bosses are more shadowy. Ruthless individualism is practically celebrated.

The same glorification of alpha dogs has occurred in other such works. My eldest son, who used to work in advertising, saw it at work in the television series Mad Men. While he found it a pretty good account of the emptiness of the industry, he noted that some in his office fantasized about living Don Draper’s lifestyle.

Or to cite another instance, a student of mine years ago told me how many of her high school buddies in a working class neighborhood fantasized about being Scarface in the Al Pacino movie. Again, they focused on the cars, the houses, and the beautiful women, not the soulless and ultimately dead-end existence of the protagonist.

Back to Glengarry Glen Ross. Williamson notes that some of these film’s fans have memorized Blake’s speech and were disappointed when they found them missing from a revival of the play. In other words, they want to be Blake:

They want to swagger, to curse, to insult, and to exercise power over men, exercising power over men being the classical means to the end of exercising power over women, which is of course what this, and nine-tenths of everything else in human affairs, is about. Blake is a specimen of that famous creature, the “alpha male,” and establishing and advertising one’s alpha creds is an obsession for some sexually unhappy contemporary men. There is a whole weird little ecosystem of websites (some of them very amusing) and pickup-artist manuals offering men tips on how to be more alpha, more dominant, more commanding, a literature that performs roughly the same function in the lives of these men that Cosmopolitan sex tips play in the lives of insecure women. Of course this advice ends up producing cartoonish, ridiculous behavior. If you’re wondering where Anthony Scaramucci learned to talk and behave like such a Scaramuccia, ask him how many times he’s seen Glengarry Glen Ross.

The article then goes on to say that Trump too has always been one of these wannabe alpha males. Williamson eviscerates the president as second-tier realtors are eviscerated in the play, describing him as a man who can’t close:

Trump is the political version of a pickup artist, and Republicans — and America — went to bed with him convinced that he was something other than what he is. Trump inherited his fortune but describes himself as though he were a self-made man.

We did not elect Donald Trump; we elected the character he plays on television.

He has had a middling career in real estate and a poor one as a hotelier and casino operator but convinced people he is a titan of industry. He has never managed a large, complex corporate enterprise, but he did play an executive on a reality show. He presents himself as a confident ladies’ man but is so insecure that he invented an imaginary friend to lie to the New York press about his love life and is now married to a woman who is open and blasé about the fact that she married him for his money. He fixates on certain words (“negotiator”) and certain classes of words (mainly adjectives and adverbs, “bigly,” “major,” “world-class,” “top,” and superlatives), but he isn’t much of a negotiator, manager, or leader. He cannot negotiate a health-care deal among members of a party desperate for one, can’t manage his own factionalized and leak-ridden White House, and cannot lead a political movement that aspires to anything greater than the service of his own pathetic vanity.

If you want to get Trump mad, do not talk about him as a mean sonuvabitch. He will see that as a compliment. Describe him, rather, as soft:

He wants to be John Wayne, but what he is is “Woody Allen without the humor.” Peggy Noonan, to whom we owe that observation, has his number: He is soft, weak, whimpering, and petulant. He isn’t smart enough to do the job and isn’t man enough to own up to the fact. For all his gold-plated toilets, he is at heart that middling junior salesman watching Glengarry Glen Ross and thinking to himself: “That’s the man I want to be.” How many times do you imagine he has stood in front of a mirror trying to project like Alec Baldwin? Unfortunately for the president, it’s Baldwin who does the good imitation of Trump, not the other way around.

Williamson concludes his piece with a final blow: Trump is actually Shelley Levene, played in the film by Jack Lemmon. Levene is an over-the-hill salesman who whines constantly about how he’s the victim of unfairness and who commits a theft to keep from getting fired, only to be ruthlessly cut down by the play’s end.

Live by the alpha dog mythos and you’ll die by it. Unfortunately, if you’re in Trump’s position you can take a lot of people down with you.