Tuesday

Among the other things we learned (and had confirmed) from the January 6 hearings are that entitled people in power will use every means available to stay in power—and if they can’t do so legally, they will employ violence. Setting a mob loose on Congress and on Vice President Mike Pence was not Trump’s first option but it was his predictable last one.

I’ve been thinking about Trump-inspired violence in terms of Richard Slotkin’s 1992 study of the Western, Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America. As Slotkin observes, America has often framed political violence as a frontier drama. Although America is hardly the only country to experience violence—in fact, most countries have bloody histories—its particular way of processing its past is to frame it as a drama involving attempts to subdue a recalcitrant wilderness. What emerges is a myth—Slotkin calls it the American myth—of “regeneration through violence.”

Throughout American history, he says, there have been different versions of this myth, from the Puritans emphasizing

the achievement of spiritual regeneration through frontier adventure; Jeffersonians (and later, the disciples of Turner’s “Frontier Thesis” [seeing] the frontier settlement as a re-enactment and democratic renewal of the original “social contract”; [or] Jacksonian Americans [seeing] the conquest of the Frontier as a means to the regeneration of personal fortunes and/or of patriotic vigor and virtue.”

Trumpism is closest to the Jacksonian model, but in each case, Slotkin says, the Myth

represented the redemption of American spirit or fortune as something to be achieved by playing through a scenario of separation, temporary regression to a more primitive or “natural” state, and regeneration through violence.

When Trump in 2017 gave his “American carnage” inaugural address, describing America as a nation under attack by forces domestic and foreign (Muslims, urban Blacks, Central American immigrants), he was invoking this myth, which may be why his vision has resonated with so many. When he has praised the tactics used by thuggish dictators like Vladimir Putin or Kim Jong-un, or when he has pardoned Navy Seal Eddie Gallagher, the court-martialed psycho killer, so-called responsible Republicans could rationalize that his actions were the primitive means needed to regenerate American society. Trump might be crude, they often said, but sometimes a society needs such crudeness to shake things up.

It should be noted that, while the “regeneration through violence” myth had its origins in the Indian wars, it has mapped easily onto other American conflicts, including those involving race and labor movements. For instance, in D.W. Griffith’s racist masterpiece Birth of a Nation, one sees the KKK playing the role of the U.S. calvary, riding to the rescue of people under assault from, not Indians but rampaging ex-slaves. Because they do so, Northerners and Southerners can reunite after their bitter war and a new nation can be born.

One sees the myth played out in many of Hollywood’s greatest westerns, such as High Noon, The Searchers, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, and others. In the 1970s, the western got transferred to urban settings but the theme was the same: Dirty Harry resorts to primitive means, with thugs now playing the role previously taken by Indians, as he deals out the violence necessary to restore civilization.

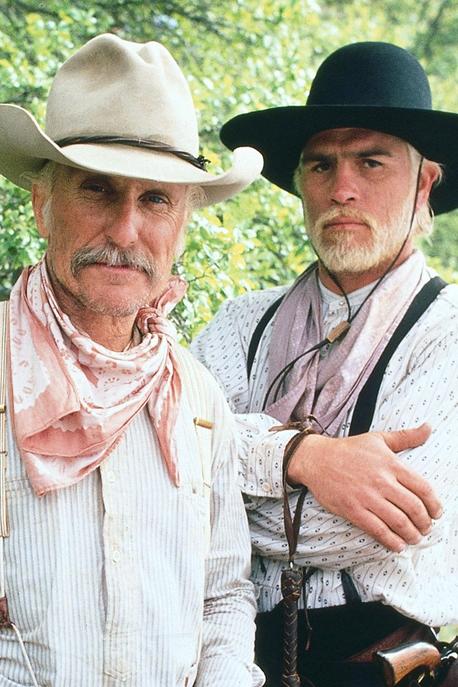

Slotkin focuses mainly on cinema in his study, but one finds literary westerns grappling with the same theme. Two novels that come to mind are Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove and Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian or the Evening Redness in the West. Lonesome Dove mourns (like Frederick Jackson Turner) the closing of the frontier, conveying a sense that the age of heroes is past once we’ve civilized the entire nation. While one is reading the novel, however, one cheers on Gus and Cal, the two Texas rangers who take the law into their own hands. Such actions are necessary in a landscape that includes a murderous Indian (Blue Duck) and a pathological gang of outlaws (the Suggs Brothers).

In the end, the rangers prevail, showing cattlemen that they can take their cattle from Texas to Montana’s green pastures. In their success, however, the rangers render themselves obsolete. Like John Wayne in a number of his movies, Cal cannot join the civilization he has helped bring about. In the process, however, the violence that he and Gus have resorted to has served its purpose.

Blood Meridian focuses less on the regeneration than on the violence as the murderous Judge Holden goes rampaging through the 19th century American west, killing Indians and settlers alike. In the end, he is proclaiming that he will never die, which may be how McCarthy sees America. Perhaps exposing the comforting myth that society can in fact be regenerated. McCarthy’s novel disturbs because it suggests that violence, not social order, always gets the last word.

Trump and Trumpism certainly focus more on violence than on social stability. Only an authoritarian leader, they claim, can bring the safety and security that people crave. The result is cult worship of a leader who praises violent crackdowns. It’s also a formula for perpetual violence.