Thursday

In case you haven’t heard the story, apparently someone in the Trump administration doctored a hurricane map to cover for the president’s fabricated assertion that Dorian posed a threat to Alabama. The incident reminded Politico’s Jeff Greenfield of Joseph Heller’s Catch-22.

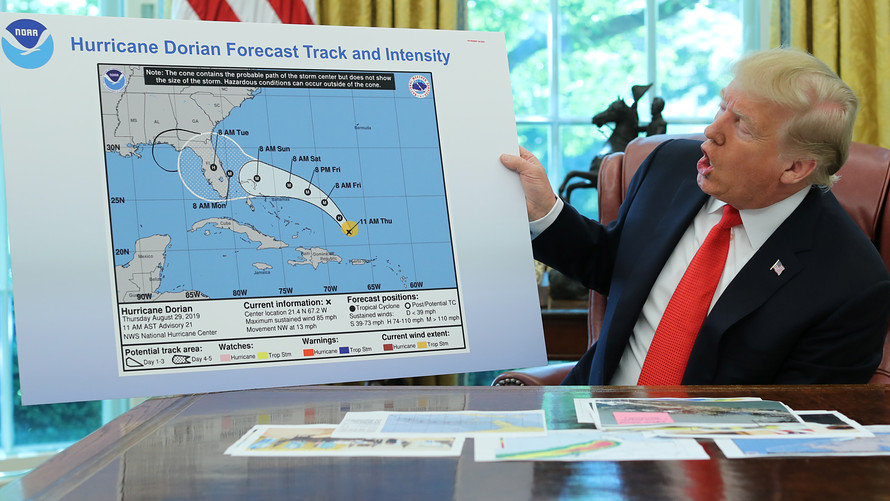

The doctoring involved using a sharpie to extend the hurricane track (see picture above). It was designed to counteract the National Weather Service in Birmingham, which following Trump’s announcement issued an immediate correction:

Alabama will NOT see any impacts from #Dorian. We repeat, no impacts from Hurricane #Dorian will be felt across Alabama. The system will remain too far east.

Rather than admitting he had been wrong, Trump doubled down, making up things left and right:

Actually, we have a better map than that which is going to be presented, where we had many lines going directly — many models, each line being a model — and they were going directly through. And in all cases Alabama was hit if not lightly, in some cases pretty hard. … They actually gave that a 95% chance probability.

Greenfield’s Heller reference involves a bombing line:

This is right out of Catch-22 when someone moves the “bombing line” on an official map to show that Pianosa is in allied hands, so that a highly dangerous bombing mission gets called off.

Actually it’s Bologna, not Pianosa, but Greenfield’s gets the rest right. The men come to hate the bombing line because it reflects a reality that they don’t like:

All through the day, they looked at the bomb line on the big, wobbling easel map of Italy that blew over in the wind and was dragged in under the awning of the intelligence tent every time the rain began. The bomb line was a scarlet band of narrow satin ribbon that delineated the forwardmost position of the Allied ground forces in every sector of the Italian mainland

…The resentments incubating in each man hatched into hatred. First they hated the infantrymen on the mainland because they had failed to capture Bologna. Then they began to hate the bomb line itself. For hours they stared relentlessly at the scarlet ribbon on the map and hated it because it would not move up high enough to encompass the city. When night fell, they congregated in the darkness with flashlights, continuing their macabre vigil at the bomb line in brooding entreaty as though hoping to move the ribbon up by the collective weight of their sullen prayers.

The rational Clevinger is mystified:

‘I really can’t believe it,’ Clevinger exclaimed to Yossarian in a voice rising and falling in protest and wonder. ‘It’s a complete reversion to primitive superstition. They’re confusing cause and effect. It makes as much sense as knocking on wood or crossing your fingers. They really believe that we wouldn’t have to fly that mission tomorrow if someone would only tiptoe up to the map in the middle of the night and move the bomb line over Bologna. Can you imagine? You and I must be the only rational ones left.’

Yossarian then pulls off a Trumpian move, redrawing a map to obtain the reality he wants:

In the middle of the night Yossarian knocked on wood, crossed his fingers, and tiptoed out of his tent to move the bomb line up over Bologna.

Trump appears to have faced few consequences for fabricating fake news. Reality still means something in World War II, however, leading to the capture of Major de Coverley:

Moving the bomb line did not fool the Germans, but it did fool Major de Coverley, who packed his musette bag, commandeered an airplane and, under the impression that Florence too had been captured by the Allies, had himself flown to that city to rent two apartments for the officers and the enlisted men in the squadron to use on rest leaves.

Yes, we’re living in a Catch-22 world.