Monday

I share today a magnificent blog essay written by one Kirsten Ellen Johnsen applying two Faust stories to Donald Trump’s manufactured immigrant children crisis. To do it justice, I’ll write about her use of Goethe in today’s post and her use of Thomas Mann in tomorrow’s.

The slogan on the back of Melania Trump’s jacket helped Johnsen make her initial connection to Goethe’s Faust: “I really don’t care. Do U?” It’s not clear why the first lady would wear such a jacket while visiting children separated from their families, but the idea of not caring is a key point in Faust. Johnsen writes that, by wearing the words, Melania

not only sent a message to the American people; she sent a message to the Gods. In Goethe’s Faust, these words echo the refusal of Faust to acknowledge Care, just before the perilous jaws of hell open for him. Whether or not her message was conscious matters not at all to the forces of myth.

Towards the end of the poem, Faust wants to drain the shoreline to expand human dominion, but standing in his war are Baucus and Philemon, who function in Greek mythology as the archetypes of hospitality:

In The Metamorphosis of Ovid, Baucus and Philemon are an elderly couple who live in a homely hut by a stagnant marsh. A beautiful linden tree grows nearby. When the Olympian gods Jupiter and Mercury wander on their journeys “in mortal guise,” they are refused shelter “at a thousand doors.” Finally they are welcomed by a humble old couple. Baucis and Philemon are poor, but invite the strangers in and feed them what they have available. As their wine bowl begins to replenish itself, the old couple realizes their guests are not ordinary. “Begging pardon for food so meager… they got set to kill their only goose.” To prevent this act of self-sacrifice, the gods reveal themselves. In return for their great hospitality, the hut of Baucus and Philemon is transformed into a temple in the middle of the swamp. Jupiter offers them a wish to fulfill, and they simply ask to serve the temple as long as they live, and once their time is up, they simply wish to die together. The story of Baucus and Philemon is a famous tale of the sacred honor of hospitality to strangers and the power of love. They are the original border keepers, welcoming refugees with warm hearts. Their story speaks of the gift of the stranger: the arrival of God at the door. To welcome the stranger is to tend that temple.

In Trump’s case, the strangers from south of the border symbolically threaten his vision of white dominion. Trump’s sense of entitlement is captured in Goethe’s poem by the phrase “the world I own”:

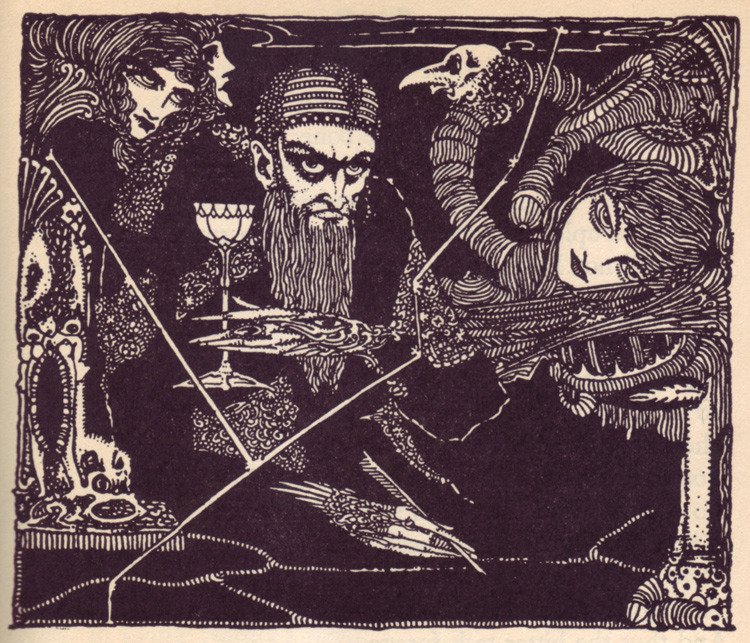

Faust is enraged at Baucus and Philemon’s resistance to his plans to requisition their shoreline. “That aged couple must surrender/I want their linden for my throne/The unowned timber-margin slender/Despoils me for the world I own.” His plans to drain the ocean he considers his “achievement’s fullest sweep” as a “masterpiece of sapient man. Before Faust’s will to conquer, even the bloom of the linden tree annoys him. Listening to Faust’s complaint, Mephistopheles eggs him on, “one has to tire of being just,” he cajoles him, “have you not colonized long since?” Mephistopheles is, of course, well aware of the significance of Faust’s decision to clear Baucis and Philemon from their ancient, mythic home in his closing line of the scene: “There once was Naboth’s vineyard, too.” Mephistopheles is referring to the Old Testament story of murder and betrayal of a man of God for his land by the the vilified Canaanite Priestess-Queen Jezebel. Complying with Faust’s wishes, he and his lackeys visit the old couple and set their hut ablaze.

The story is only getting started, however. The occasion may initially involve attacking those who welcome strangers, but it evolves into a spiritual crisis when Faust is visited by four spirits who arise from the “vapors of the ashes” of the hut: the four Gray Crones of Want, Debt, Need, and Care.

Faust keeps the first three from entering his house but he is not entirely able to dismiss Care, the key word on Melania’s jacket. If Faust or the president were to care about what they were doing, then their human reaction potentially could check their actions (Faust’s expansion plans, Trump’s zero-tolerance immigration policies). Faust, unlike the Trumps, acknowledges the power of caring but then, like the Trumps, chooses not to care:

Revealing herself, [Care] demands of him, “Am I unknown to you?” Faust refuses her. “All I did was covet and attain/and crave afresh, and thus with might and gain/stormed through my life,” he preens, with the excuse that an able man may seize and “stride upon this planet’s face.” Care has given him one last chance to repent, but he has failed. “Desist! This will not work on me!/such caterwauling I despise.” Even as he finally rejects her, he admits, “yet your power, o Care, insidiously vast/I shall not recognize it ever.” Care then curses Faust: “Man is commonly blind throughout his life/My Faust, be blind then as you end it.” Faust’s own proclamation is his curse: “I really don’t care, do U?”

The curse reminds me of what Jesus predicts for those who sin against the Holy Spirit: “Truly I tell you, all sins and blasphemes will be forgiven for the sons of men. But whoever blasphemes against the Holy Spirit will never be forgiven, but is guilty of an eternal sin.” The sin is unforgivable because when we violate our own inner holiness, we lose the capacity to love and to care.

It’s a lot easier to turn away strangers in need and to separate children from their parents when we don’t care. It’s interesting to watch the gyrations of certain Trump supporters as they seek to mimic his not caring. His use of words like “infest,” “breed,” and “invade” are designed to make such detachment easier. After all, if the immigrants are not human, then it is more permissible not to care. Because our essential humanity does not go down without a fight, however, we are witnessing a fair amount of cognitive dissonance among Fox News and other Trumpists.

Johnsen sums up what is at stake:

It is the act of hospitality that humanizes us. This is where we are leveled. The capacity for compassion, for Care, breaks open one’s heart. To destroy the Sacred Guest — the sacred act of recognizing the heart of another human being — is the ultimate mythic sacrilege, for in this betrayal lies the seed for all crimes against humanity. Care may be the only Gray Crone who might slip unnoticed into the hearts of the rich, but Goethe does not suggest that the rich might save the world through finally discovering compassion, or even worry. He is saying that the moral failure of willful, blind uncaring ultimately portends spiritual downfall.

The crisis of Trumpism is spiritual as well as political. Hold on to Care, for to turn your back on her is to lose your soul.