Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Thursday

We returned to the States to discover that Fox’s Tucker Carlson, who had remade himself into a racist nativist, has been fired by Rupert Murdoch. Of the many commentaries I’ve read about the bow-tied pundit, one surprised me by invoking a forgotten novel that I haven’t read since high school.

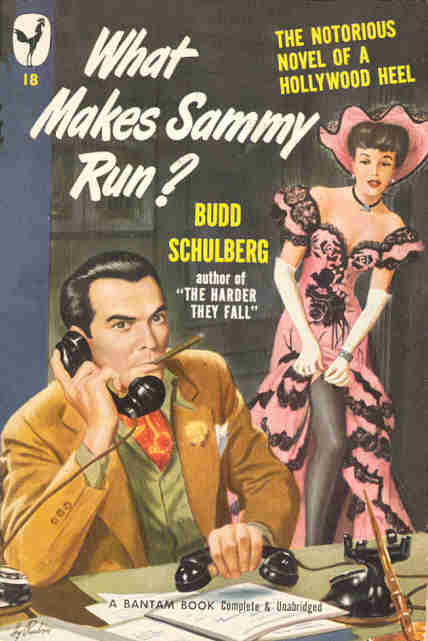

Mother Jones’s David Corn has alluded to Bud Schulburg’s What Makes Sammy Run in an attempt to figure out Carlson’s strange trajectory from seemingly reasonable rightwing intellectual to white supremacist. In Corn’s eyes, he is a “Sammy Glick of the Right”:

What happened to Carlson? Perhaps nothing. Maybe from the start he was nothing but an opportunistic guy on the make. A Sammy Glick of the right. As a young reporter, he seized the opportunity to brand himself as a conservative journalist different from other right-wing scribes in the combative Age of Clinton. Years later, as that glow wore off (and his television career started slipping), he reinvented himself as an angry populist cheerleader of the Trumpish right. That’s where the audience and the big bucks were—and the influence. It’s possible that along the way he even convinced himself of some of what he was saying. But the likely explanation is that truth never mattered: It was all about status and money.

Comparing Glick and Carlson is somewhat strange in that Glick is a working class kid fanatically driven to rise in the world—a kind of Jewish Gatsby—whereas Tucker Swanson McNear Carlson grew up in privileged surroundings, attending first a private boarding school and then one of the small ivies, Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut. But like Sammy, Carlson appears to be willing to do and say anything to succeed. As Sammy says at one point in his rapid rise to Hollywood mogul, “Going through life with a conscience is like driving your car with the brakes on.”

Unlike Carlson, Sammy is a product of New York’s “dog eat dog” Lower East Side. The narrator meets him when, at 16, he is a copyboy for a newspaper. By the end, through stealing scripts, shamelessly using and discarding acquaintances, stabbing his principled boss in the back, and leaving his girlfriend to strategically marry the daughter of the Wall Street banker representing the film company’s financiers, Sammy rises to the top, becoming a producer.

Then, having reached the pinnacle, he experiences the emptiness of a life where everything has been transactional. When he catches his wife Laurette Harrington making love to an actor he has just hired, she informs him that their marriage is no more than a business affair. His response is to order Shiek, his personal servant, to find him a prostitute.

Before this occurs, however, he tells the narrator that he has achieved everything he ever wanted. I wonder whether Tucker Carlson, when he ruled the world of cable television, ever thought similarly. The scene occurs when Glick is looking out his window at Hollywood in action:

“Now it’s mine,” Sammy said. “Everything’s mine. I’ve got everything. Everybody’s always saying you can’t get everything and I’m the guy who swung it. I’ve got the studio and I’ve got the Harrington connections and I’ve got the perfect woman to run my home and have my children.”

I sat there as if I were watching The Phantom of the Opera or any other horror picture. I sat there silently in the shadows, for it was growing dark and the lights hadn’t been switched on yet and I think he had forgotten he was talking to me. It was just his voice reassuring him in the dark.

“Sammy,” I said quietly, “how does it feel? How does it feel to have everything?”

He began to smile. It became a smirk, a leer.

“It makes me feel kinda..” And then it came blurting out of nowhere—“patriotic.”

If you see the American Dream as achieving personal success, then I suppose you could interpret your ascension to the heights as patriotic. But success paid for with one’s soul is ultimately empty, as the narrator reflects after having seen Glick turn to paid sex after discovering his wife’s affair:

I drove back slowly, heavy with the exhaustion I always felt after being with Sammy too long. I thought of him wandering alone through all his brightly lit rooms. Not only tonight, but all the nights of his life. No matter where he would ever be at banquets, at gala house parties, in crowded night clubs, in big poker games, at intimate dinners, he would still be wandering alone through all his brightly lit rooms. He would still have to send out frantic S.O.S.’s to Sheik, the virile eunuch. Help! Help! I’m lonely. I’m nervous. I’m friendless. I’m desperate. Bring girls, bring Scotch, bring laughs. Bring a pause in the day’s occupation, the quick sponge for the sweaty marathoner, the recreational pause that is brief and vulgar and titillating and quickly forgotten, like a dirty joke.

Tucker Carlson is far from the only Sammy Glick in the rightwing media. Tom Nichols, Atlantic writer and former Republican, identifies the type. In the 1990s, he says, the new generation of young conservatives

realized that the way to dump their day jobs for better gigs in radio and television was to become more and more extreme—and to sell their act to an audience that was nothing like them or the people at D.C. dinner parties. They would have their due, even if they had to poison the brains of ordinary Americans to get it.

Carlson, as Nichols sees it, is

emblematic of the entire conservative movement now, and especially the media millionaires who serve as its chief propagandists. The conservative world has become a kind of needle skyscraper with a tiny number of wealthy, superbly educated right-wing media and political elites in the penthouses, looking down at an expanse of angry Americans whose rage they themselves helped create.

If your only criteria for success is how much wealth and/or power you can amass—I’m thinking of such unprincipled politicians as Ted Cruz, Josh Hawley, and Lindsey Graham here as well as Carlson—then you are doomed to a perpetual restlessness. Or as Schulberg’s narrator puts it, “always thinking satisfaction is just around the bend.” You run incessantly without ever finding peace.

And sooner or later, as Schulberg narrator notes, there will be other Sammy Glicks overtaking you—or in Carlson’s case, other Fox commentators—at which point you may come face to face with the emptiness inside you.