Friday

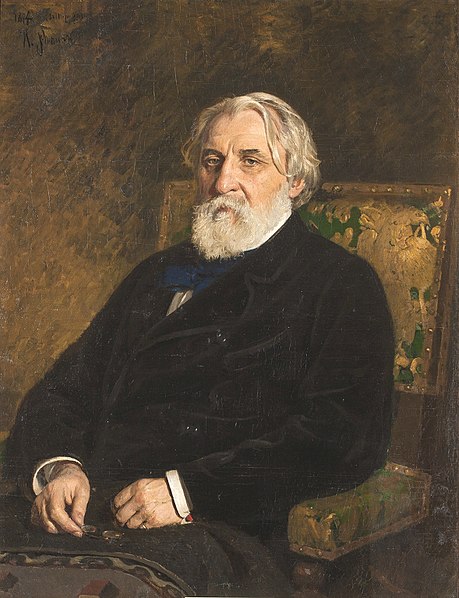

The blog “Literary Hub” has alerted me to an essay asserting that the short stories of Turgenev played a role in emancipating the Russian serfs in 1861. According to Pakistani-American author Daniyal Mueenuddin, the Russian nobility were so oblivious to the humanity of the serfs that they couldn’t imagine what emancipation would look like. A Sportsman’s Notebook (1852) helped change that.

Born into a prominent landowning family, Turgenev saw up close the brutality enacted against the serfs. Both his grandmother and mother were despotic women, with the former once having beaten a page-boy to death, while Turgenev witnessed his mother abusing one of his own illegitimate daughters. (He would go on to free her and set her up independently.)

In his introduction to the recently reissued collection, Mueenuddin notes,

These stories are as much informed by his mother’s despotism as by the larger despotism of the Russian state. His personal revolt ran parallel to a larger national political revolt. Through his childhood and later as a man, Turgenev sought out the company of the serfs in the kennels and kitchens of Spasskoye because among them he found kindness.

As to how the stories contributed to the emancipation, Mueenuddin writes,

Unusually, for a work of fiction—for any work of art—the Notebook played an important political role in the history of Russia. In the middle of the 19th century, the necessity of liberating the serfs, who were virtually slaves, had become pressing upon an increasingly westernized nobility. The necessity of their liberation, and then the means and outlines of that emancipation, puzzled the nobles and most importantly, the czar—Alexander II.

This constituency found it difficult to reconcile itself to the loss of their revenues and powers flowing from this emancipation in part because they knew very little about their serfs, had never paid much attention to them. They commanded obedience with banishments and the knout, and otherwise indulged themselves with serf orchestras on their estates and desperate feats of gambling and spoke French among themselves. If they gave it any thought, they would have considered it an impertinence for their serfs to have private lives.

Turgenev’s stories imposed the humanity of these men and women upon their owners, showed them in all their complexity. The stories came as a revelation to their readership. Any man who’s ever killed a chicken knows that it’s best not to look it in the eye. Turgenev forced his fellow landowners to do that, look the serfs in the eye. Alexander II acknowledged the role these stories played in guiding him to issue the Emancipation Edict that freed the serfs in 1861.

This past year I read for the first time Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons and was impressed by its humanity and vitality. Apparently, such a vision had the power to influence a czar. Literature can’t change history by itself, but it can play a vital role.