Wednesday

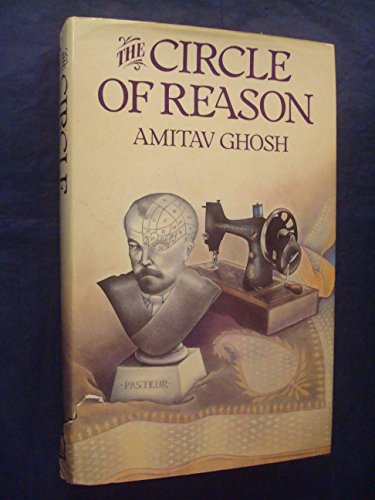

I’ve fallen in love with the novels of India’s Amitav Ghosh and at the moment have Circle of Reason, his first novel, rolling around in my head. It functions as a good cautionary tale for those intellectuals, idealists, and ideologues who get so stuck in their heads that they lose touch with reality and become vulnerable to those who care only about money and power. We who believe in clean government and science-guided policy need to pay attention.

The novel follows two generations of Indians. First there is Balaram, a schoolteacher who becomes obsessed first with phrenology (the study of skulls) and then hygiene. Then there is his nephew Alu, a skilled weaver who has a prophetic vision of cleanliness that grips an immigrant community in Al Jazirah, United Arab Emirates. In both instances, a genuine but naïve idealism is depicted as nefarious and destroyed by corrupt officials.

After several years as a teacher in a rural school, Balaram sets up his own “School of Reason.” In the “Pure Reason” track the villagers are taught basic literacy and in the “Practical Reason” track they learn weaving and sewing. The school flourishes and starts making money, but Balaram has higher aspirations, as he explains to the students and teachers:

A school, like Reason itself, must have a purpose. Without a purpose Reason decays into a mere trick, forever reflecting itself like mirrors at a fair. It is that sense of purpose which the third department will restore to our school. It will help us remember that we cannot limit the benefits of our education and learning to ourselves—that it is our duty to use it for the benefit of everybody around us. That is why I have decided to name the department the Department of the March of Reason. It will remind us that our school has another aspect: Reason Militant.

Inspired from an early age by René Vallery-Radot’s The Life of Pasteur, Balaram decides that Reason Militant’s first project will be to eradicate the village’s germs, and he purchases barrels of carbolic acid, an antiseptic. A local politician with his own agenda, a character I’ve compared to Trump, convinces the authorities that the school compound is a terrorist bomb factory. In the subsequent police raid, the acid catches fire and everyone but Alu dies.

Labeled a terrorist, Alu flees to Al Jazirah, where he works in the country’s underground economy while living in the Ras, an immigrant community. When a shoddy construction project collapses upon him, he has a vision as he awaits help. This he shares with others in the Ras. Having been raised by his uncle, he begins by telling them about Pasteur:

Purity. Purity was what [Pasteur] had wanted, purity and cleanliness—not just in his home, or in a laboratory or a university, but in the whole world of living men. It was that which spurred him on his greatest hunt, the chase in which he drove the enemy of purity, the quintessence of dirt, the demon which keeps the world from cleanliness, out of its lairs of darkness, and gave it a name—the Infinitely Small, the Germ.

But where do germs originate? Pasteur doesn’t know but Alu’s vision has provided him with the answer:

Money. The answer is money.

The crowd gasped, and while they were still reeling he shouted again: We will wage war on money. Are you with me?

And the whole crowd shouted back: Yes. Yes. Yes.

No money, no dirty will ever again flow freely in the Ras. Are you with me.

And again the crowd roared: Yes.

We will drive money from the Ras, and without it we shall be happier, richer, more prosperous than ever before.

The vision manifests itself as communal sharing and, for a while, it works. People do in fact make more money than ever before, and those few businesses who resist the communal contract are boycotted until they surrender. To celebrate, community members organize a grand shopping expedition and also carry ropes and utensils to salvage two old sewing machines that Alu was trying to rescue when the building collapsed.

Once again, however, good intentions are misinterpreted or deliberately distorted by the authorities, who see a riot rather than an innocent excursion. Riot police attack and Alu, already labeled a terrorist, barely escapes. Everyone else is either killed or, lacking work permits, expelled from the country.

The danger of Reason becoming a circle that cuts one off from the messiness of humanity is an idea I first encountered in a sophomore French Revolution course at Carleton College. Carl Wiener assigned us J. L. Talmon’s The Origins of Totalitarian Democracy, in which he argues (I’m relying on a 50-year-old memory here) that Rousseau’s Enlightenment ideas led to Robespierre led to the reign of terror led to various 20th century totalitarianisms. Reason becomes a hermetic circle because it focuses more on its defining principles than on the people who are supposed to act reasonably. Classic conservatism, which can be more realistic about our flawed natures than idealistic liberalism, works as a necessary corrective.

Talmon points out that, if reasoners attain power, they sometimes punish those who don’t fit into their neat little boxes. On the other hand, if they don’t achieve power, idealists can be crushed by those who cynically manipulate revolutionary idealism—or the reaction against it—for their own ends. In some instances, as Arthur Koestler points out in his novel Darkness at Noon, idealists may assent to their own annihilation, mistaking Stalinism for the revolutionary ideals they dream of rather than as a movement coopted by a mass-murderer.

I’ve written about New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik disputing a version of this thesis. The liberalism of Voltaire and Rousseau did not lead to fascism, he convincingly argues. Whatever the case, the immigrants in Circle of Reason have no real power and suffer dire consequences.

Fortunately for Alu, he has a pragmatic friend in an Indian woman named Zindi, a force of nature who foresees the outcome and saves him, along with the prostitute Kulfi and the baby of a woman who is killed.

They flee to Algeria, where we encounter a third circle of reason. The refugees are adopted by Dr. Uma Verma, an Indian doctor who wants to use Kulfi in an ancient India play she is directing. She finds opposition to her project in a colleague, the ultra-rational Dr. Mishra, who doesn’t believe in (as he sees them) superstitious rituals or religious customs.

Because of his upbringing, however, Mishra is thoroughly versed in both and incessantly critiques first Verma’s theatrical project and then, after Zulfi dies in rehearsal, her determination to have a Hindu cremation. If one is going to observe such rituals, he believes, they must be done by the book (another form of purity). The follow interchange occurs after Verma begs some ghee from Mrs. Mishra, having learned from Mishra that Indian butter is ritually essential:

So you’re really going ahead with this? he said. You’re going to broil her on rotten wood and baste her with rancid butter? It’s shameful. It’s a travesty. Can’t you see that?

The times are like that, Mrs. Verma said sadly. Nothing’s whole anymore. If we wait for everything to be right again, we’ll wait forever while the world falls apart. The only hope is to make do with what we’ve got.

The cremation occurs in spite of all Mishra’s objections, and even he must admit that something special has happened. From a purist’s standpoints, the cremation may be a travesty, but in a world where purity and idealism are invariably tainted or crushed, one does the best one can.

The Democratic Party at the moment appears to have learned this lesson and is now willing to blend idealism with pragmatism, welcoming a wide range of political allies into its tent. “If we wait for everything to be right again, we’ll wait forever while the world falls apart. The only hope is to make do with what we’ve got.” Which in this case is Joe Biden.