Monday

Our trip to Slovenia is proving a wondrous experience in every way but one: we find ourselves eating far too much. And for eating too much, I can think of no better literary episode than one in Booth Tarkington’s Penrod. A passage from a book I hadn’t read since childhood came rushing back to me yesterday when we were dining out with four former exchange students who lived with us while studying at St. Mary’s College of Maryland.

I thought I was being careful as I ordered only a salad after having just spent a full afternoon dining with the family of another former student. For this earlier meal, we journeyed to Novo Mesto—meaning New City—which is the the childhood home of two other Slovenians who lived with us at different times. Although “Novo Mesto” means “New City,” it’s a bit of a misnomer since it was officially founded in the 14th century, and we viewed artifacts from earlier settlements (including stone age implements) in the city museum.

Anyway, for dinner we had roast turnkey, roast pork ribs, two kinds of potatoes, a lettuce salad, a cabbage salad, buckwheat, a very good bottle of Croatian red wine, some of Slovenia’s excellent dark bread, and all topped off with coffee and a gluten free cake with cherries. Oh yes, there was also homemade apricot schnapps.

And then, two hours later, there we were eating again and hearing about our students reminisce about their time in America. A number of them talked about how it was the best year of their lives, and we could relate because we felt the same about the two Fulbright years we spent in Slovenia. But wonderful as it all was, I went home determined never to eat another bite.

Which is where Penrod (1914) comes in. Penrod is Tarkington’s version of Tom Sawyer, appearing in a series of stories where he is constantly getting in trouble. In this particular story, he finds himself suddenly rich after his sister’s boyfriend bribes him with a dollar to keep him out of the way. Penrod takes the windfall to a local fair and spends most of it on food. He starts off with a large pickle and lemonade:

The cries of the peanut vendors, of the popcorn men, of the toy-balloon sellers, the stirring music of the band, playing before the performance to attract a crowd, the shouting of excited children and the barking of the dogs within the tent, all sounded exhilaratingly in Penrod’s ears and set his blood a-tingle. Nevertheless, he did not squander his money or fling it to the winds in one grand splurge. Instead, he began cautiously with the purchase of an extraordinarily large pickle, which he obtained from an aged negress for his odd cent, too obvious a bargain to be missed. At an adjacent stand he bought a glass of raspberry lemonade (so alleged) and sipped it as he ate the pickle. He left nothing of either.

Next he turns to a tin of sardines (“He consumed the sardines utterly, but left the tin box and the fork”) and “an inexpensive half-pint of lukewarm cider,” after which “the cool, sweet cadences of the watermelon man fell delectably upon his ear.” The watermelon slice is followed a bag of peanuts “heavily larded with partially boiled molasses,” at which point “a sense almost of satiety beg[an] to manifest itself to him.”

Satiety or not, a “sense of duty oblige[s] him to consume” three waffles, thickly powered with sugar.” Then, discovering that “they had not been quite up to his anticipation,” he figures he needs some Neapolitan ice-cream to cool him down. Instead, he discovers that “it fell short of the desired effect, and left a peculiar savor in his throat.”

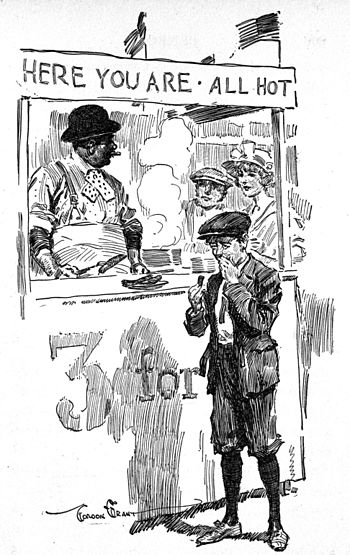

Another sign that all is not well is that he finds himself passing a fresh-taffy booth “with strange indifference.” (“He did not analyze his motives: simply, he was conscious that he preferred not to look at the mass of taffy.”) Then he encounters the sausage (or weenie) stand, and the story movies toward crisis:

This, above all nectar and ambrosia, was the favourite dish of Penrod Schofield. Nothing inside him now craved it—on the contrary! But memory is the great hypnotist; his mind argued against his inwards that opportunity knocked at his door: “winny-wurst” was rigidly forbidden by the home authorities. Besides, there was a last nickel in his pocket; and nature protested against its survival. Also, the redfaced man had himself proclaimed his wares nourishing for the weak stummick.

Penrod placed the nickel in the red hand of the red-faced man.

What happens next is almost enough to make the reader as sick as Penrod:

He ate two of the three greasy, cigarlike shapes cordially pressed upon him in return. The first bite convinced him that he had made a mistake; these winnies seemed of a very inferior flavor, almost unpleasant, in fact. But he felt obliged to conceal his poor opinion of them, for fear of offending the red-faced man. He ate without haste or eagerness—so slowly, indeed, that he began to think the redfaced man might dislike him, as a deterrent of trade. Perhaps Penrod’s mind was not working well, for he failed to remember that no law compelled him to remain under the eye of the red-faced man, but the virulent repulsion excited by his attempt to take a bite of the third sausage inspired him with at least an excuse for postponement.

Rather than spell out the grand finale–it’s a bow to 1914 decorum–Tarkington plays with color associations to signal how it all ends:

For a time he stared without attraction; the weather-worn colours conveying no meaning to comprehension at a huge canvas poster depicting the chief his torpid eye. Then, little by little, the poster became more vivid to his consciousness. There was a greenish-tinted person in the tent, it seemed, who thrived upon a reptilian diet.

Suddenly, Penrod decided that it was time to go home.

I didn’t eat quite this recklessly. Still, I would have been more comfortable had I paid more attention.