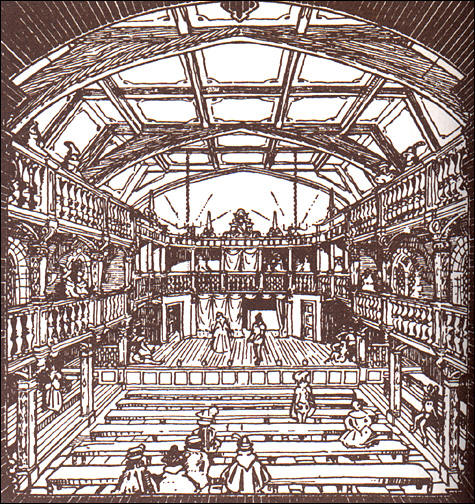

Blackfriars Theater

This past Saturday I got a front row view of what it would have been like watching Shakespeare in the early 17th century. Julia and I journeyed to the replica of the Blackfriars Theater in Staunton, Virginia to watch Comedy of Errors and also John Marston’s 1603 revenge drama The Malcontent. Some of drama’s greatest plays debuted at the original Blackfriars, including King Lear, and I found the experience to be electrifying. I also returned with some fresh support for this website’s foundational premise: that art is supposed to mix it up with life.

At the Blackfriars, I witnessed less of a separation between audience and drama than I am accustomed to seeing. The plays were performed in full light—there was no darkening of the theater—and up to ten audience members were able to sit on stage. I watched delighted as some of my students interacted with the actors (at the actors’ instigation), exchanging high fives and fist bumps in the course of the plays.

The energy was high even before the performances began, thanks to a very lively musical introduction. As would have been the case in the 17th century, the actors themselves played and sang during the 15 minutes prior to the opening and during the intermission, creating a rock concert type feel. When they shifted, almost without pause, into a very slapstick version of Comedy of Errors, the energy carried over.

A similarly thin divide separated the afternoon performance of The Malcontent. The play is (among other things) a satire against vices of the time, and at times the actors would directly address certain audience members as though they were identifying actual culprits. In 1603 they may well have been doing so.

Beth Charlebois, our college’s Shakespearean who arranged the trip, told me that new insights into the Bard open up when one sees his plays performed in replica spaces. Beth herself spent three weeks at the Blackfriars for an NEH seminar and had a chance to stage scenes from The Winter’s Tale. She notes that a skilled playwright would write to the lighting conditions so that, for instance, the frightening scene where the baby is carried off would have occurred when the candles in the chandelier were burning low. By contrast, the subsequent scene—the pastoral island—would have occurred when the candles had been restocked, providing a lighter mood.

I’m not an expert in performance and so don’t know when theater began to separate audience from actors. I wonder, however, whether it occurred in the 19th century when art was placed on a pedestal, separate from life. This was the age of “art for arts sake,” and arts were often seen as a counterweight to soul-draining industrialization.

To be sure, raising art up appears a compliment. If (to quote Percy Shelley) poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world, then why not honor them? But separating them out has also served to make them seem irrelevant.

Anyway, art was up close and personal at the Staunton Blackfriars. We audience members were delighted with how we had to shift constantly between the fiction and the realization that we were watching a fiction.

Speaking of taking art off its pedestal, there was an interesting article in the New York Times last week about the relationship between the golden age of British Theater and money. I didn’t realize that one reason why Shakespeare, Marlowe, and others flourished in the late 16th century is because there was suddenly a lot of money to be made. As the article notes,

At day’s end, actors and theater owners smashed open the earthenware moneyboxes and divided the daily take. From those proceeds dramatists were paid to write new plays. For the first time ever, it was possible to earn a living writing for the public.

Money changed everything. Almost overnight, a wave of brilliant dramatists emerged, including Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Kyd, Ben Jonson and Shakespeare. These talents and many comparable and lesser lights had found the opportunity, the conditions and the money to pursue their craft.

To cite the old Marxist maxim, it was a case of economic base determining ideological (including cultural) superstructure. The point of the article was that there can be dire artistic consequences when money dries up so be careful about art-for-free on the web. Whether or not this is true in modern times, it certainly rings true for what I know of Shakespeare. When his long narrative poem Venus and Adonis didn’t fare well financially, he stopped writing long poems. It’s sobering to think that Shakespeare probably wouldn’t have written his plays if the financial structure hadn’t been such that he could become rich off of them.

So much for art for art’s sake.

Addendum

My colleague Beth Charlebois provided the following answer to my question about when audiences began watching drama in the dark:

To at least partially answer your question in the post: As you noted, the porous boundary between audience and actor is really cultivated by what the folks at the Blackfriars have come to call “universal lighting,” where actors and audience members are illuminated in the same level of light. During the summer of 2002 when I participated in the NEH institute, “Shakespeare’s Playhouses Inside and Out,” I learned that the English loved universal lighting even more than their Continental counterparts, who began putting their audiences in the dark far earlier. If you can believe it, in England it really wasn’t until the advent of cinema (when movie houses started darkening the auditoriums so that audiences could better see the images on the screen) that it became a theatrical convention! Thought you’d find that interesting!