Thursday

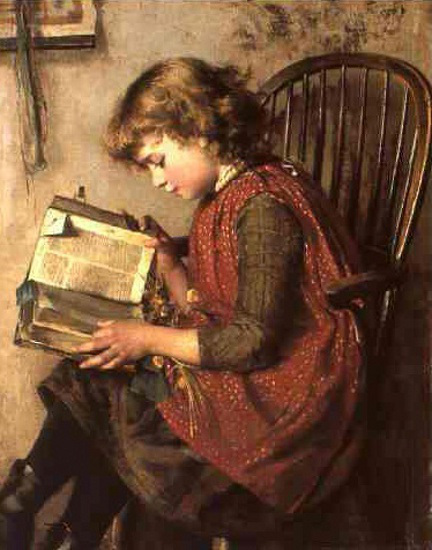

In my Theories of the Reader class, I’m currently having my students write their personal reading histories. This comes after their having read two articles by Freud and an article by Freudian psychologist Norman Holland. Today I explain how these works help the students delve deeper into the meaning of their reading experiences.

In the assignment, the students are to choose three intense encounters that they have had with works of literature and figure out who they were at the time that explains why they had the experience that they did. The works are to come at different stages of their lives—I encourage them to start with a childhood reading encounter—and, in addition to explaining the reading dynamics, they must also figure out a theme that connects that three works. Drawing on Holland’s article “Unity Identity Text Self,” I call this their “identity theme.”

Holland says that, just as works of literature have a unifying theme, so do people. We call this theme our “identity,” which Holland defines by quoting psychologist Heinz Lichtenstein:

When we describe the “character” or “personality” of another person, Lichtenstein shows, we abstract an invariant from “the infinite sequence of bodily and behavioral transformations during the whole life of an individual.” That is, we can be precise about individuality by conceiving of the individual as living out variations on an identity theme much as a musician might play out an infinity of variations on a single melody. We discover that underlying theme by abstracting it from its variations.

Holland wrote his essay in 1975, before the heyday of deconstruction, and we don’t make textual unity the holy grail of literary criticism anymore–just as, perhaps, psychologists don’t still look for a single identity within an individual. Still, even deconstructionists look for an attempted unity, even if only to then blow it up. (Deconstruction’s characteristic move is to show how a seemingly unified text unravels or contains fault lines that have been “sutured.”) In the assignment, I find it useful to have the students look for a central drama to their lives, one which has continued from their childhood to the present day. They often find it clarifying to realize that a childhood struggle is still playing itself out in their lives 15 or 20 years later. At the very least, this is one of their identities.

Holland says that readers replicate their identity in the act of reading:

As readers, each of us will bring different kinds of external information to bear. Each will seek out the particular themes that concern him. Each will have different ways of making the text into an experience with a coherence and significance that satisfies.

Much of Holland’s work has been to explore how this act of replication works. In Poems in Persons, for instance, he shows how different interpretations of a single work can be traced back to the different identities of the readers. In my own assignment, I have the students choose different works—ones with which they have had a strong encounter, whether positive or negative—and then, in the final analysis, find a connecting theme in the reactions they had to those works.

I can report that a theme always emerges. Sometimes it is very clear, as when, say, people uncomfortable with the tradition expectations assigned to their gender find themselves drawn to characters who transgress gender norms. This can be such a painful struggle that the stories and poems they find are immensely reassuring. Likewise, it is not uncommon to find women students identifying a longing to be strong as their identity theme after they have examined their works and reactions. Other identity themes are harder to ferret out, sometimes because the student hasn’t provided enough biographical background or enough detail about the reading experiences. Sometimes it takes a revision to find clarity.

Freud’s essay “The Poet and Daydreaming” proves useful in helping the students understand the meaning of childhood stories. Freud says that, when they play, children are essentially creative writers:

Might we not say that every child at play behaves like a creative writer, in that he creates a world of his own, or rather, rearranges the things of his world in a new way which pleases him? It would be wrong to think he does not take that world seriously; on the contrary, he takes his play very seriously and he expends large amounts of emotion on it.

One way children to play is by listening to stories. When children demand that their parents read them a particular book 25 or 50 times, they are looking for answers to life’s critical problems as they experience them. Once the issue no longer seems so critical, children will suddenly lose all interest in the story.

While the issues may change as we grow older, our underlying identities don’t. What we find pleasurable remains constant, Freud say. Instead of abandoning our childhood pleasures, we find find adult substitutes or surrogates:

But whoever understands the human mind knows that hardly anything is harder for a man than to give up a pleasure which he has once experienced. Actually, we can never give anything up; we only exchange one thing for another. What appears to be a renunciation is really the formation of a substitute or surrogate. In the same way, the growing child, when he stops playing gives up nothing but the link with real objects; instead of playing, he now phantasies. He builds castles in the air and creates what are called day-dreams. I believe that most people construct phantasies at times in their lives.

Extending this observation to the act of reading, we can say that, having once enjoyed reading as children, we never give it up but seek for the same pleasure in adult substitutes. One reason my students can find themes through works read at different points in time is because the later books bear some relationship to the earlier ones. It’s just that, having bigger minds now, they demand more complex literary experiences.

In “Poets and Daydreaming,” Freud boils our daydreams—and I would add, our reading wishes—down to two: ambitious wishes and erotic wishes. These, he believes, are gendered male and female, and before we reject his bifurcation too quickly as a 19th century holdover, it’s worth noting that men still lean toward action adventure and women toward romance (although this is gradually changing).

The more important point for my students is that they search out the wishes within their reading experiences.

But wishes aren’t the whole story, as Freud himself came to realize. In Beyond the Pleasure Principle, he grappled with the fact that we don’t only fantasize wishes but also anxieties. He discovered this from studying the PTSD nightmares of World War I veterans, in which they revisited their trench experiences.

Bringing the fantasy closer to home, Freud tells the story of a child, otherwise well behaved, who was obsessed with throwing toys. In doing so, Freud says, he was replaying the story of abandonment by the mother. Since no fear goes deeper, why would a child replay it, shouting “fort” (gone) as the toy disappeared? Freud also witnessed a variant: the child had a reel attached to a string, which he would first disappear (“fort”) and then retrieve (“da” or “there”). The child would replay the fort/da story and over.

Freud proffers several explanations, but one is that, by articulating his anxiety with the “fort” game, the boy reassured himself that he had control over the situation. He, rather than the mother, determined when the disappearance occurred.

With the fort/da variant, meanwhile, anxieties are followed by reassurance of a happy ending. We visit the fear but then console ourselves that a satisfactory resolution is possible. When we grow up, we never tire of this story, although we do insist on more complexity.

I therefore tell my students to look for the anxieties in their reading experiences as well as the wishes. If we are reading to survive the natural shocks that flesh is heir to, we must revisit those shocks to fully appreciate literature’s power.

When the assignment succeeds, the students come away with a deeper appreciation for the gift of literature. After all, time and again it stepped up to support them in their times of direst need.