Thursday

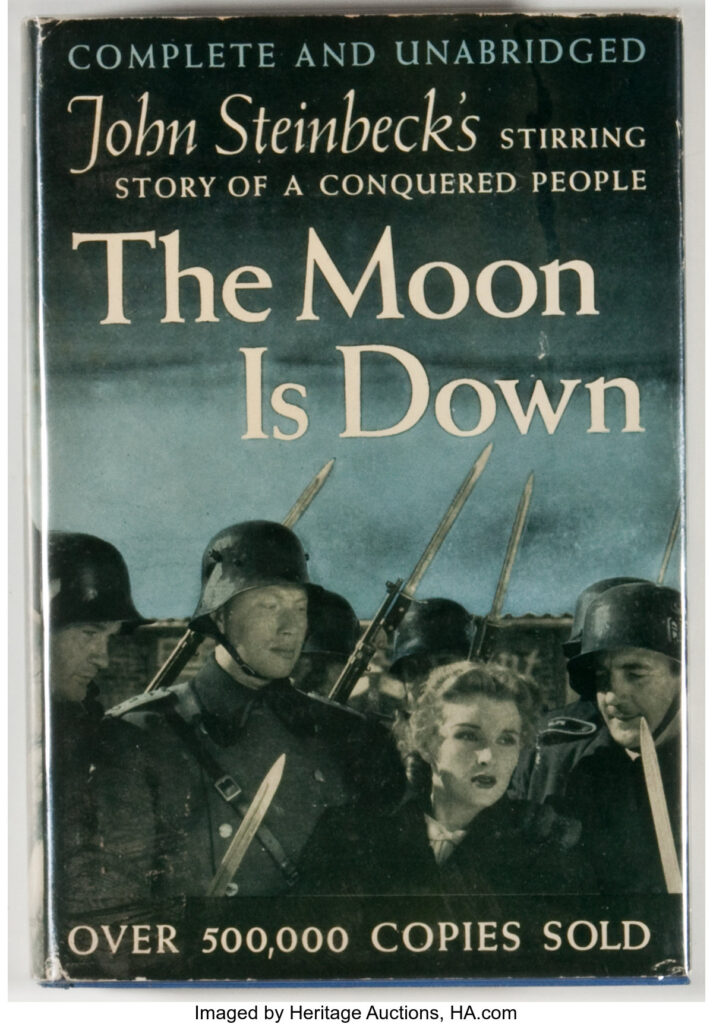

I’ve been following the twitter feed of retired Major Mack Ryan, who has been closely covering the war in Ukraine, and he recently quoted from a John Steinbeck novel that I read in high school and that could well become relevant. The Moon Is Down is about Germany’s occupation of Norway during World War II, and if Russia in fact manages to conquer Ukraine—no sure thing—then it will face a comparable insurgency. In fact, the Russian conquerors would probably fare even worse than the Germans did since the Ukrainians are better armed and have more outside support.

I quote an extended passage to capture the hell individual Russian soldiers can expect:

Now it was that the conqueror was surrounded, the men of the battalion alone among silent enemies, and no man might relax his guard for even a moment. If he did, he disappeared, and some snowdrift received his body. If he went alone to a woman, he disappeared, and some snowdrift received his body. If he drank, he disappeared. The men of the battalion could sing only together, could dance only together, and dancing gradually stopped and the singing expressed a longing for home. Their talk was of friends and relatives who loved them and their longings were for warmth and love, because a man can be a soldier for only so many hours a day and for only so many months in a year, and then he wants to be a man again, wants girls and drinks and music and laughter and ease, and when these are cut off, they become irresistibly desirable.

And the men thought always of home. The men of the battalion came to detest the place they had conquered, and they were curt with the people and the people were curt with them, and gradually a little fear began to grow in the conquerors, a fear that it would never be over, that they could never relax and go home, a fear that one day they would crack and be hunted through the mountains like rabbits, for the conquered never relaxed their hatred. The patrols, seeing lights, hearing laughter, would be drawn as to a fire, and when they came near, the laughter stopped, the warmth went out, and the people were cold and obedient. And the soldiers, smelling warm food from the little restaurants, went in and ordered the warm food and found that it was oversalted or overpeppered.

Then the soldiers read the news from home and from the other conquered countries, and the news was always good, and for a while they believed it, and then after a while they did not believe it anymore. And every man carried in his heart the terror. “If home crumbled, they would not tell us, and then it would be too late. These people will not spare us. They will kill us all.” They remembered stories of their men retreating through Belgium and retreating out of Russia. And the more literate remembered the frantic, tragic retreat from Moscow, when every peasant’s pitchfork tasted blood and the snow was rotten with bodies.

And they knew when they cracked, or relaxed, or slept too long, it would be the same here, and their sleep was restless and their days were nervous. They asked questions their officers could not answer because they did not know. They were not told, either. They did not believe the reports from home, either.

Thus it came about that the conquerors grew afraid of the conquered and their nerves wore thin and they shot at shadows in the night. The cold, sullen silence was with them always.

By shelling civilian targets, the Russians are hoping to grind the Ukrainians down, but Steinbeck points out that fear works both ways and that those whose homes have been invaded have the long-run advantage. As Ryan observes after quoting this last paragraph, “The Russians must grow very afraid of Ukrainians.”