Wednesday

Writing last week for the New York Times’ “What Is Power?” series, Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari argued that fiction is a more powerful force than truth in politics. I extend the discussion to literature (which Harari does not discuss) because of its reliance upon fabrication in the service of a higher understanding. Camus, after all, wrote, “Fiction is the lie through which we tell the truth,” and Khaled Hosseini, “Writing fiction is the act of weaving a series of lies to arrive at a greater truth.”

Grasping how fiction works has become urgent given that we have a president who lies incessantly while systematically attacking those organizations and institutions tasked with providing us truthful accounts of reality (colleges and universities, investigative and other governmental agencies, the courts, the press, the scientific establishment).

As he did in his book Sapiens, Harari declares that human beings became the world’s dominant species because their ability to tell stories made large-scale cooperation possible. We need common stories to unify us, he declares, but then adds that

these stories need not be true. You can unite millions of people by making them believe in completely fictional stories about God, about race or about economics.

How do we reconcile our susceptibility to fiction with our scientific beliefs? Harari chalks it up to compartmentalization. Even as Nazi Germany believed in a bogus master race narrative, for instance, it also produced highly sophisticated scientists and engineers. Having an advanced degree doesn’t mean you won’t be gullible in other areas.

Interestingly, Harari sees such compartmentalization in the Enlightenment itself, pointing out that

the Scientific Revolution began in the most fanatical culture in the world. Europe in the days of Columbus, Copernicus and Newton had one of the highest concentrations of religious extremists in history, and the lowest level of tolerance.

Newton himself apparently spent more time looking for secret messages in the Bible than deciphering the laws of physics. The luminaries of the Scientific Revolution lived in a society that expelled Jews and Muslims, burned heretics wholesale, saw a witch in every cat-loving elderly lady and started a new religious war every full moon.

By contrast, the Ottoman Empire was “a liberal paradise”:

If you had traveled to Cairo or Istanbul around 400 years ago, you would have found a multicultural and tolerant metropolis where Sunnis, Shiites, Orthodox Christians, Catholics, Armenians, Copts, Jews and even the occasional Hindu lived side by side in relative harmony….If you had then sailed on to contemporary Paris or London, you would have found cities awash with religious bigotry, in which only those belonging to the dominant sect could live. In London they killed Catholics; in Paris they killed Protestants; the Jews had long been driven out; and nobody even entertained the thought of letting any Muslims in. And yet the Scientific Revolution began in London and Paris rather than in Cairo or Istanbul.

Given the horrors associated with these religious narratives, what are we to make of literary fiction? Well, not all fiction is the same. What distinguishes great from not-so-great literature is its adherence to truth. The greatest authors are committed to depicting the world as it is whereas lesser authors often opt for convenient, popular, or ideologically correct fictions.

If Chaucer could create a multi-dimensional Wife of Bath at a time when misogynist caricatures of women reigned supreme, it’s because he was committed to capturing her full humanity. Shakespearean scholar Stephen Greenblatt observes that the Bard’s “ability to enter deeply—too deeply, for the purposes of the plot—into almost every character he deployed was a signature.” Dostoevsky begged the official censor to let him retain the graphic images of child abuse that appear in The Brothers Karamazov since, without them, Ivan’s diatribe about senseless suffering loses its power. Thomas Hardy felt compelled to stir up a hornet’s nest by calling Tess “a pure woman” since conventional Victorian morality couldn’t do justice to a woman like her.

In other words, great fiction exposes less fiction. As such, it can be just as “painful and disturbing” as Harari finds truth in politics to be:

[T]he truth is often painful and disturbing. Hence if you stick to unalloyed reality, few people will follow you. An American presidential candidate who tells the American public the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth about American history has a 100 percent guarantee of losing the elections. The same goes for candidates in all other countries. How many Israelis, Italians or Indians can stomach the unblemished truth about their nations? An uncompromising adherence to the truth is an admirable spiritual practice, but it is not a winning political strategy.

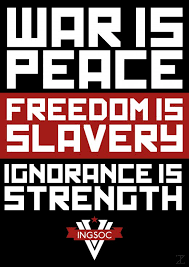

In order to win, should we all become cynics? Literature argues otherwise, with works like Macbeth pointing to the dark paths down which political expediency can take us. When we read and teach great literature, we see the dangers of selling our soul. Loving Big Brother or chanting “Lock them up” at a Trump rally may provide a temporary high, but ultimately it hollows us out.

On the other hand, when a literary masterpiece ushers us into our full humanity, we ask ourselves why we ever settled for less.