Sports Saturday

Mais où sont les neiges d’antan?

François Villon

There’s not much going on in the sports world at the moment. Soccer’s World Cup now seems like a dream, the last major golf tournament has been played (with Tiger magic seemingly on indefinite hold), and football, basketball, hockey, and tennis’s U.S. Open await in the future. So do college athletics, although yesterday I glimpsed our College’s soccer and field hockey teams returning to campus. Outside of baseball, which seems to move more to the slow rhythms of daily life than to the adrenaline pumping explosiveness of staged events, we are in a dry season.

Come to think of it, maybe that’s why August politics seem to have become so confrontational in recent years. Maybe it’s because, in the absence of bread and circuses, we look for drama elsewhere. If that’s the case then, please God, let the football season begin.

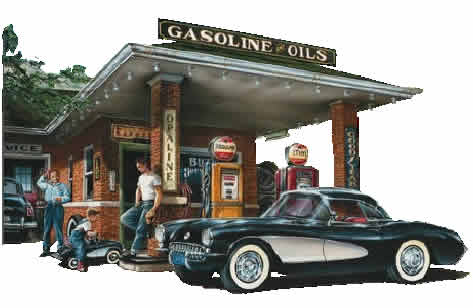

Anyway, my father alerted me to an elegiac poem by the late John Updike on what happens after a sports career is over. Note how it begins with an image of a road abruptly ending. High school athletes who aren’t going on to college, college athletes who graduated in May and are looking for work, athletes with professional league aspirations who find themselves getting cut during preseason tryouts, all may see themselves in Updike’s poem. So may anyone else for whom the lug wrenches of life fail to acknowledge the “wild birds” they once had for hands.

Although we may no longer be players, we will always be dreamers. Here’s the poem:

Ex-Basketball Player

By John Updike

Pearl Avenue runs past the high-school lot,

Bends with the trolley tracks, and stops, cut off

Before it has a chance to go two blocks,

At Colonel McComsky Plaza. Berth’s Garage

Is on the corner facing west, and there,

Most days, you’ll find Flick Webb, who helps Berth out.

Flick stands tall among the idiot pumps—

Five on a side, the old bubble-head style,

Their rubber elbows hanging loose and low.

One’s nostrils are two S’s, and his eyes

An E and O. And one is squat, without

A head at all—more of a football type.

Once Flick played for the high-school team, the Wizards.

He was good: in fact, the best. In ’46

He bucketed three hundred ninety points,

A county record still. The ball loved Flick.

I saw him rack up thirty-eight or forty

In one home game. His hands were like wild birds.

He never learned a trade, he just sells gas,

Checks oil, and changes flats. Once in a while,

As a gag, he dribbles an inner tube,

But most of us remember anyway.

His hands are fine and nervous on the lug wrench.

It makes no difference to the lug wrench, though.

Off work, he hangs around Mae’s Luncheonette.

Grease-gray and kind of coiled, he plays pinball,

Smokes those thin cigars, nurses lemon phosphates.

Flick seldom says a word to Mae, just nods

Beyond her face toward bright applauding tiers

Of Necco Wafers, Nibs, and Juju Beads.