Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Thursday – July 4th

Walt Whitman wrote “I Hear America Singing” in 1860, which is to say, a year before the Civil War. In other words, he expressed faith in American democracy at a time when its future was even more in doubt than it is today. In Whitman’s time, his mechanics, carpenters, and masons would soon be spilling blood over the question of whether this “new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal” could “long endure.”

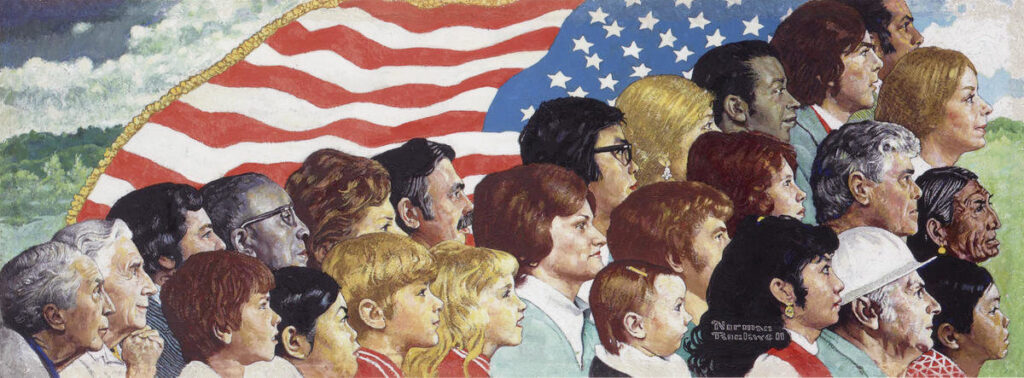

Today, with Trump’s Supreme Court attempting to invest all power in (1) an imperial presidency and (2) its own invented rules, we ask the same question. Lest we lose faith, we have Whitman to remind us that our greatness lies in our diversity.

I hear America singing, the varied carols I hear,

Those of mechanics, each one singing his as it should be blithe and strong,

The carpenter singing his as he measures his plank or beam,

The mason singing his as he makes ready for work, or leaves off work,

The boatman singing what belongs to him in his boat, the deckhand singing on the steamboat deck,

The shoemaker singing as he sits on his bench, the hatter singing as he stands,

The wood-cutter’s song, the ploughboy’s on his way in the morning, or at noon intermission or at sundown,

The delicious singing of the mother, or of the young wife at work, or of the girl sewing or washing,

Each singing what belongs to him or her and to none else,

The day what belongs to the day—at night the party of young fellows, robust, friendly,

Singing with open mouths their strong melodious songs.

And to supplement these Americans with a few more–to make clear that Whitman’s America is ethnically diverse–here are some from Song of Myself:

I saw the marriage of the trapper in the open air in the far west, the bride was a red girl,

Her father and his friends sat near cross-legged and dumbly smoking, they had moccasins to their feet and large thick blankets hanging from their shoulders,

On a bank lounged the trapper, he was drest mostly in skins, his luxuriant beard and curls protected his neck, he held his bride by the hand,

She had long eyelashes, her head was bare, her coarse straight locks descended upon her voluptuous limbs and reach’d to her feet.

The runaway slave came to my house and stopt outside,

I heard his motions crackling the twigs of the woodpile,

Through the swung half-door of the kitchen I saw him limpsy and weak,

And went where he sat on a log and led him in and assured him,

And brought water and fill’d a tub for his sweated body and bruis’d feet,

And gave him a room that enter’d from my own, and gave him some coarse clean clothes,

And remember perfectly well his revolving eyes and his awkwardness,

And remember putting plasters on the galls of his neck and ankles;

He staid with me a week before he was recuperated and pass’d north,

I had him sit next me at table, my fire-lock lean’d in the corner.

In other words, the essence of America is not white Christian.

When I was a Fulbright scholar at the University of Ljubljana’s English Department in 1987, my officemate, an old Slovenian Melville scholar, once observed that he couldn’t figure out how America worked. He knew what it meant to be Slovenian—after all, there was the Slovenian language and a fairly homogeneous Slovenian culture—but what did it mean to be American?

When I thought about it, the American experiment really seemed to me to be extraordinary. To think there could be a unified country made of multiple ethnicities, religions, languages (don’t forget the Native American languages), and diverse past histories was an extraordinary exercise in hope. The Declaration of Independence and Constitution, supplemented by the poem on the Statue of Liberty and other key documents (including Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech), have somehow held us together even in the worst times.

Our poets and novelists have made a major contribution to this unifying narrative.