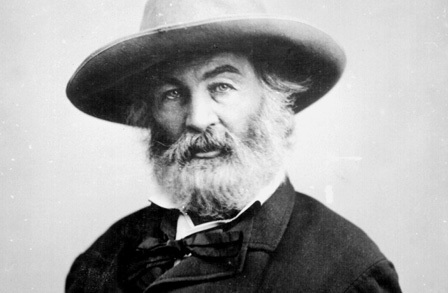

My novelist friend Rachel Kranz is currently serving a two-week stint in our College’s Artist’s House. and we have been talking about the power of literature to change the very categories by which people define reality. Rachel has steered me to a remarkable book on the radical abolitionists, The Black Hearts of Men, where author John Stauffer discusses how Walt Whitman and Herman Melville helped America imagine new ways of seeing itself.

Whitman’s vision was radical because it broke down barriers that were foundational to oppression. Here’s Stauffer:

In his 1855 Leaves of Grass Whitman articulated an empathic vision of America surpassing even that described by Radical Abolitionists a week earlier at Syracuse. Their respective visions shared many of the same features. Both visions evoked a democracy of inclusion, but without its inherent flaw—dating back to the Greeks—of forging that inclusion by excluding women, slaves, and blacks. Both portrayed a sacred society in which divinity dwelled within all people. Both contained an aesthetic of fluidity and connectedness between one person and another (and between Whitman and the reader), regardless of differences. And both contained elements of the sublime. For Whitman, the sublime appeared in the grotesque images of Southerners and Northerners, prostitutes and saints, blacks and whites, all living together in harmony. But while Radical Abolitionists at Syracuse focused on the means for achieving the new age, Whitman assumed that it had already arrived. For Whitman, his poetry itself created the condition of pluralist society that was no longer burdened by sin. It was in his poetry, rather than in his prose works or his life, that the new age was possible.

Stauffer notes that Melville offered up a similar vision and that at least one abolitionist, African American James McCune Smith, picked up on it. In his amazing Republic of Letters, Smith depicted an ideal society that drew inspiration from Moby-Dick. Here’s Stauffer describing Smith’s vision:

His new “republic” consisted of a series of sketches—ten in all, the last one completed in late 1854—depicting working-class black men and women as heroic and dignified Americans in a retrograde society that had rejected them…The portraits range in type from a news-vendor, bootblack, washerwoman, and sexton, to a steward, inventor, whitewasher, and schoolmaster. Their work is the key to their character; it is what defines them, rather than their race, class, or gender. In McCune Smith’s Republic of Letters, there is no essential difference between men and women, black and white, rich and poor.

Do you see any resemblance to Moby-Dick? Here’s Stuffer:

[Smith’s] narrator and characters contain many of the same features as Ishmael and Queequeg, who form an intimate friendship by working, praying, and sleeping together despite their cultural and racial differences. Both Melville’s and McCune Smith’s characters undermine the cultural dichotomies on which the social order depended. As Ishmael says, he and Queequeg stand above the jeering glances of mainstream Americans—“a lubber-like assembly, who marveled that two fellow beings should be so companionable; as though a white man were anything more dignified than a white-washed negro.”

Stauffer makes a point about Whitman that I find interesting. Although Whitman put forth a radical new vision in his poetry, in his life and in his journalistic writings, he was unwilling to befriend blacks and to “act on the revolutionary ideas in his poetry. “Be radical—but not too damned radical,” he once counseled someone. While he opposed slavery, he was not in favor of immediate abolition.

I’ve noted frequently in this blog that literature is often wiser than we are. “We” includes the author. When we are in the grip of a poem or a story, we often see things that we are otherwise blind to. Whitman’s poetry took him places where his feet could not follow.

And here’s an interesting point about Smith’s use of Moby-Dick. Few readers knew about the novel and, for that matter, few people read Smith. Not all literature hits with the cataclysmic force of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Yet powerful ideas have a way of shifting the conversation and perhaps Moby-Dick, like Stowe’s work, played a role in The Emancipation Proclamation and the 14th Amendment.