We still don’t have a definitive answer as to why, last September, aides of New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie closed down two of the three access lanes to the world’s busiest bridge, thereby creating gridlock in Fort Lee, New Jersey for four straight days. The common belief has been that Christie wanted to punish Fort Lee Mayor Mark Sokolich for refusing to endorse his reelection bid. However, after reading about the testimony of Matt Mowers before a legislative investigative committee this past Tuesday, I’m beginning to think that Voltaire’s Candide provides the real answer.

To bring you up to date on the latest developments, Mowers, a former staffer in Christie’s administration and later his campaign, was questioned about a list of Democratic mayors that Christie targeted for endorsement. The more Democratic support he could get, the Republican governor figured, the more he would appear a crossover candidate in the 2016 presidential race. Mowers told of a conversation he had with Christie aide Bridget Kelly asking him if Sokolich would be endorsing Christie. Mowers told her no, to which she reportedly replied, “Okay, that’s all I need to know.” It was early the next morning when she sent the infamous e-mail, “Time for some traffic problems in Fort Lee.”

It sounds like the plan to close access lanes was already in place and Kelly was just double checking on whether Sokolich had changed his mind. Upon learning that he remained recalcitrant, she signaled to Christie’s man in the Port Authority, David Wildstein, to pull the trigger. (His e-mail reply, delivered within minutes, was, “Got it.”)

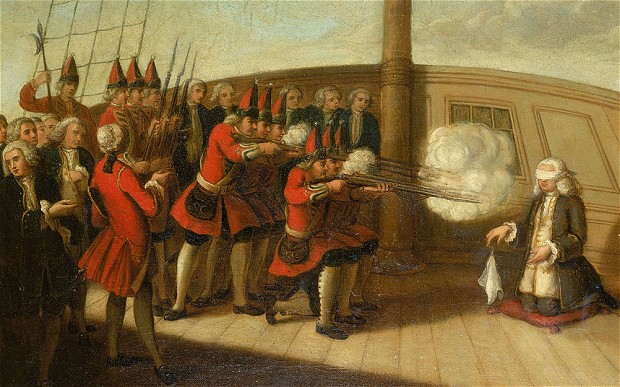

But although it now seems clear that Sokolich was the target, the question still remains why. Why would the Christie administration take all this trouble to single out one mayor of a fairly small city when all the signs were that Christie was headed for a comfortable reelection. This is where Voltaire helps us see clearly. The episode in Candide is based on the real life execution, pictured above, of Admiral John Byng:

As they were chatting thus together they arrived at Portsmouth. The shore on each side the harbor was lined with a multitude of people, whose eyes were steadfastly fixed on a lusty man who was kneeling down on the deck of one of the men-of-war, with something tied before his eyes. Opposite to this personage stood four soldiers, each of whom shot three bullets into his skull, with all the composure imaginable; and when it was done, the whole company went away perfectly well satisfied.

“What the devil is all this for?” said Candide, “and what demon, or foe of mankind, lords it thus tyrannically over the world?”

He then asked who was that lusty man who had been sent out of the world with so much ceremony. When he received for answer, that it was an admiral.

“And pray why do you put your admiral to death?”

“Because he did not put a sufficient number of his fellow creatures to death. You must know, he had an engagement with a French admiral, and it has been proved against him that he was not near enough to his antagonist.”

“But,” replied Candide, “the French admiral must have been as far from him.”

“There is no doubt of that; but in this country it is found requisite, now and then, to put an admiral to death, in order to encourage the others.”

Or to quote the original French, “pour encourager les autres.”

Sokolich may have just been small fry but perhaps the signal wasn’t just for him. To bend the state to his will, perhaps Christie needed examples. Why is it found requisite, in New Jersey, to now and then put the screws to a mayor?

Pour encourager les autres.