Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Sunday

Julia and I have joined a weekly group that engages in the practice of Lectio Divina, a “traditional monastic practice of scriptural reading, meditation and prayer intended to promote communion with God and to increase the knowledge of God’s word” (Wikipedia). Each week we discuss a Biblical passage and musical selection chosen by the organizer of the group, which includes some very insightful people with extraordinary backgrounds. The sessions so far have been rich and rewarding.

Our first reading three weeks ago provided a perfect introduction. It included the parable of the mustard seed, itself one of Jesus’s most mind-bending stories, but what most caught my eye was a meta moment where Matthew reflects on the practice of using parables itself:

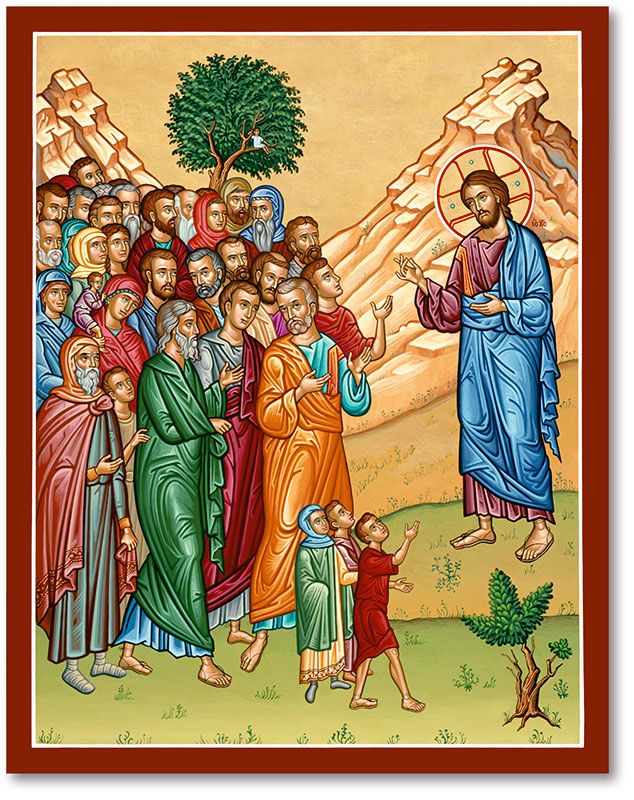

He put before them another parable: ‘The kingdom of heaven is like a mustard seed that someone took and sowed in his field; it is the smallest of all the seeds, but when it has grown it is the greatest of shrubs and becomes a tree, so that the birds of the air come and make nests in its branches.’ He told them another parable: ‘The kingdom of heaven is like yeast that a woman took and mixed in with three measures of flour until all of it was leavened.’ Jesus told the crowds all these things in parables; without a parable he told them nothing. This was to fulfil what had been spoken through the prophet: ‘I will open my mouth to speak in parables’. (Matthew 13:31-35)

The prophet Matthew has in mind is the psalmist:

I will open my mouth in a parable: I will utter dark sayings of old…(Psalms 78:2).

It’s as though, by watching Jesus pile parable upon parable, Matthew feels the need to comment on the process. Why employ this method rather than express his point straightforwardly?

You know, of course, where I stand on this issue: literature (including stories) gets at truths that escape straight exposition. In fact, I read the whole Bible this way: Genesis does not provide us with a literal account of creation but rather provides us with a story that articulates the wonder of our origins. It also, as great stories do, raises issues that we wrestle with to this day. Religion is better served by leaving Big Bang and DNA theories to scientists and focusing rather on what our existence means.

I think also of Emily Dickinson’s admonition to “tell the truth, but tell it slant.” In her account, desiring to get the truth straight would be like Semele in Greek mythology getting obliterated after seeing Zeus in all his glory:

Tell all the truth but tell it slant —

Success in Circuit lies

Too bright for our infirm Delight

The Truth’s superb surprise

As Lightning to the Children eased

With explanation kind

The Truth must dazzle gradually

Or every man be blind —

Jesus, good teacher that he is, knows that his audiences can’t see everything that he sees and so finds a way to lead them in the right direction. Like any creative storyteller, he uses stories to involve them in the exploratory process. As reader response theorist Wolfgang Iser points out, literature is filled with gaps or indeterminate elements that readers must fill by active participation. Jesus’s auditors would have internalized the parables in a deep way by applying their own experiences to them.

Mark’s reflections remind me of an important lecture that Rob MacSwain, a C.S. Lewis scholar who teaches at Sewanee’s Theological Seminar, gave to our Adult Sunday School. You can read my full account of it here but, to sum up the highlights, it discussed Lewis’s contributions to Anglican theology.

Which at first didn’t seem like much. For one thing, as MacSwain noted in starting out, Anglicans/ Episcopalians don’t do theology.

This would distinguish them from Catholics, Lutherans, Presbyterians, Baptists, Mormons, Moravians, and various other denominations, and looking at Anglicanism’s history one can see why. Fighting over matters of doctrine was a recipe for civil war in Tudor England, which Queen Elizabeth wanted to avoid at all costs. How did one keep Catholics and radical Protestants from cutting each other’s throats? One sidestepped theological battles. As Elizabeth said at one point, “There is only one Christ, Jesus, one faith. All else is a dispute over trifles.”

Theology, which is intent on bringing everything into logical order, often concerns itself with these trifles. MacSwain said that Anglicans are particularly uninterested in systematic theology and in the currently fashionable analytic theology, which is suspicious of metaphor and ambiguity as it strives for the clearest account possible of God and religion.

After having contended that Anglicans don’t “do” theology, however, MacSwain then reversed course and said they in fact engage in it at a very deep level. They just do it through literature. He mentioned figures like John Donne, George Herbert, Henry Vaughan, Alfred Lord Tennyson, T.S. Eliot, and W. H. Auden before turning to his own focus on C.S. Lewis.

To this list, by the way, I would add Edmund Spenser, Sir Philip Sidney, Jonathan Swift, Joseph Addison, William Cowper, Christopher Smart, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Charlotte and Emily Bronte, John Keble, Gerard Manley Hopkins (who became Catholic but started off Anglican), Christina and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Anthony Trollope, George Eliot, Dorothy Sayers, Charles Williams, R.S. Thomas, John Betjeman, Malcolm Guite, Madeleine L’Engle, Richard Wilbur, and Mary Oliver. Some lean more to low church or evangelical Anglicanism, some to high church Anglicanism or even Anglo-Catholicism, but all grapple with spiritual issues in one way or other.

For his part, Lewis sometimes used poetry, sometimes fantasy (the Narnia books), sometimes science fiction (his space trilogy), sometimes other fictional forms (e.g., The Screwtape Letters) to explore issues of faith. Through literature, he and these other authors capture the emotional as well as the intellectual dimensions of spirit. What they lose in philosophical rigor (although literature has its own form of rigor), they gain through fictional immersion.

To sum up, Jesus used parables because stories engage audiences and provide truths in a way that more literal approaches cannot. Touching on buried meanings as they tap into the unconscious, they tell the truth slant. In so doing, they get us closer to God.