Tuesday

Enthusiasts of the BBC series Sherlock finally got the next installment that we’ve been awaiting for years, and I, for one, was fully satisfied. The following essay has a spoiler but not for the mystery that we are presented with. Rather, I’ll be talking about the choice to frame the episode in Victorian garb. Doing so opens up some smart insights into Arthur Conan Doyle’s original stories.

Enthusiasts of the BBC series Sherlock finally got the next installment that we’ve been awaiting for years, and I, for one, was fully satisfied. The following essay has a spoiler but not for the mystery that we are presented with. Rather, I’ll be talking about the choice to frame the episode in Victorian garb. Doing so opens up some smart insights into Arthur Conan Doyle’s original stories.

In the previous episode, Sherlock is called back from exile following the apparent return of supposedly dead Moriarty. To understand what Moriarty is (or was) up to, Sherlock casts his mind back to a similar mystery, unsolved, from late Victorian times. A bride committed suicide and then returned from the dead to kill first her own abusive husband and then a series of other harsh spouses.

Sherlock takes an overdose of his “seven percent solution” to aid him, and so everything we see is a hallucinogenic trip. It so happens that this trip takes the form of a Doyle story set during Doyle’s time period.

If a number of familiar characters appear to be a little off base, it’s because they are Sherlock’s version of them, not the actual characters. Furthermore, Sherlock has reinvented them as they might have behaved in the 19th century. (Watson comments on his ridiculous mustache.) Finally, Sherlock reinvents them as they might have been depicted in Watson’s account of them had Watson in fact been a 19th century storyteller.

In Sherlock, of course, Watson is a 21st century blogger. Sherlock is just transposing him into another century and imagining how he would have behaved and written in that century.

In other words, Sherlock is a 21st century figure imagining Watson and himself as Doyle imagined them. Of course, the scriptwriters of Sherlock are doing the reverse, recasting Doyle’s 19th century characters as 21st century characters.

Why is Sherlock imagining himself participating in a 19th century story featuring himself and Watson and written by Watson? He thinks that, by picturing the crime in its original setting with himself on the case, he can solve it.

While working on the mystery, he also engages in a metafictional analysis of Watson’s literary style—or rather, what Watson’s style would be if he were a 19th century writer rather than a 21st century blogger. In addition to being the world’s foremost detective, Sherlock also proves himself a skilled literary critic.

One can see why the show’s creators created this metafictional device. To produce their modern adaptations, they must delve deeply into Doyle’s stories, and this way they can comment on the stories’ features. Perhaps they even see this as a chance to vent, albeit with fondness, about the limitations of Doyle’s creations.

In the process, they discover that Mrs. Hudson is an overly flat character. That Sherlock’s dialogue sometimes sounds like it was written for a story rather than delivered by an actual human being. That Holmes uses Watson as a rhetorical foil. (At one point he discovers that Watson has left the room and that he is in fact talking to a chair–“I thought he’d improved,” Holmes says.) And that the stories themselves are contrived: sometimes they are overly Gothic, sometimes they are shaped more as mini-dramas than as accounts of actual crime solving.

Of course, we as readers don’t care. We just want good stories. Still, it’s fun to see their inner workings exposed.

There is a very tender twist towards the end of Sherlock’s hallucination. He has descended into his mind in order to solve the crime—remember, everything we see in 19th century garb is his imagination, not the actual Watson and Moriarty–and the mind can become a trap. Sherlock’s brother at one point says something to the effect that the most dangerous place for Sherlock is solitude. What if he were to get lost in his mind and never emerge?

This observation arises logically out of Sherlock’s description of Moriarty in the original Doyle story. Sherlock sounds like a paranoid madman or a conspiracy nutcase who has lost all touch with reality:

For years past I have continually been conscious of some power behind the malefactor, some deep organizing power which forever stands in the way of the law, and throws its shield over the wrong-doer. Again and again in cases of the most varying sorts—forgery cases, robberies, murders—I have felt the presence of this force, and I have deduced its action in many of those undiscovered crimes in which I have not been personally consulted. For years I have endeavored to break through the veil which shrouded it, and at last the time came when I seized my thread and followed it, until it led me, after a thousand cunning windings, to ex-Professor Moriarty of mathematical celebrity.

He is the Napoleon of crime, Watson. He is the organizer of half that is evil and of nearly all that is undetected in this great city. He is a genius, a philosopher, an abstract thinker. He has a brain of the first order. He sits motionless, like a spider in the center of its web, but that web has a thousand radiations, and he knows well every quiver of each of them. He does little himself. He only plans. But his agents are numerous and splendidly organized. Is there a crime to be done, a paper to be abstracted, we will say, a house to be rifled, a man to be removed—the word is passed to the Professor, the matter is organized and carried out. The agent may be caught. In that case money is found for his bail or his defence. But the central power which uses the agent is never caught—never so much as suspected. This was the organization which I deduced, Watson, and which I devoted my whole energy to exposing and breaking up.

The Moriarty in Sherlock knows about Holmes’s obsessiveness, and his design is to use Sherlock’s mind against him. Perhaps his fiendish plot is to drive Sherlock mad, even though, being dead, he won’t be there to enjoy it. But maybe he doesn’t need to be. Maybe he’s so confident that he has already enjoyed the moment, knowing that he has set in motion a trap from which Holmes cannot escape.

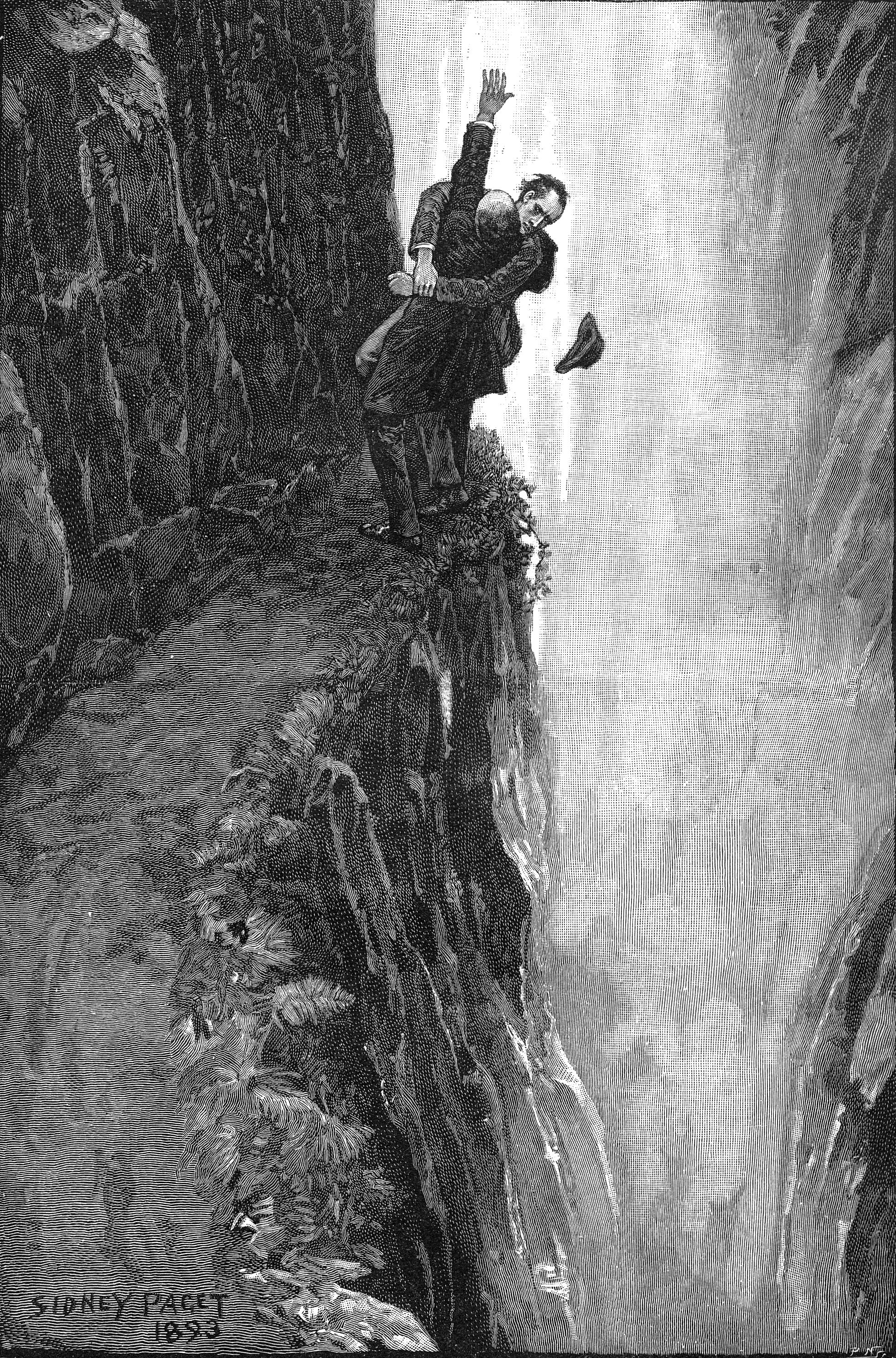

It almost works. That’s why we suddenly see Sherlock and Moriarty wrestling at the Reichenbach Falls in a scene that is modeled directly on the original Sidney Paget illustration (see above). Remember, this Moriarty is all in Sherlock’s head and he is on the verge of casting Sherlock into the abyss. The real Moriarty knew all along that he would triumph.

There’s one thing he didn’t count on, however: Sherlock has Watson to ground him. Sherlock has used Watson’s storytelling to get out of his own mind and see the situation from another vantage point. It helps him solve the crime of the abominable bride and it allows him to defeat his inner Moriarty. That’s the meaning of Watson showing up in the hallucination and pushing Moriarty over the cliff.

In other words, for all that he makes fun of Watson’s stories about him, Sherlock knows that he needs them for the narrative that connects him to the world. That’s what stories do: they give our lives meaning. Even stories with literary limitations.