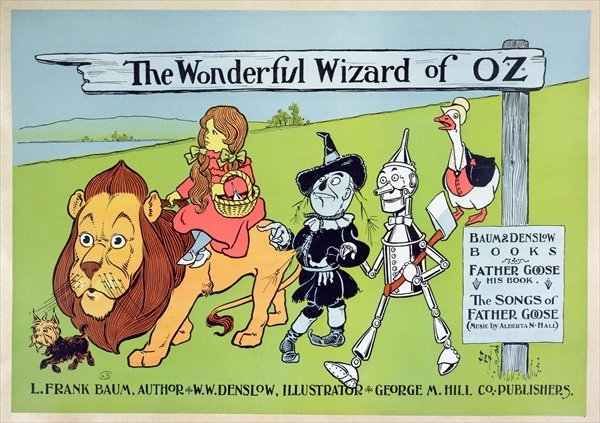

I’m currently teaching L. Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz (1900) in my American Fantasy course and am discovering that Baum’s book was a watershed event in American fantasy, comparable to the publication of Lord of the Rings in England.

It’s an open question which of the two works has been more influential. Tolkien’s trilogy has certainly had more of a literary impact, spawning the “sword and sorcery” genre that shows no appearance of abating. The Wizard of Oz, on the other hand, can be seen as leading to Walt Disney and the Disney empire.

I’ve asked my students to write about how The Wizard of Oz is an American fairy tale. In certain ways, Oz hearkens back to John Winthrop’s “city upon a hill,” that Puritan vision of America as a place to step beyond history and build God’s kingdom on earth. The vision inspired the building of “the white city” for the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, which is where Baum probably got the direct inspiration for Oz. Carl Sandburg might describe Chicago as the “hog butcher of the world,” but for Baum it was the Emerald City.

In an article entitled “There’s No Place But Home,” Jerry Griswold points out that Oz is a version of the United States. In the East there are the Munchkin farmers, versions of the prosperous and well-mannered Pennsylvania Dutch. The West, the country of the Winkies, is a wild and savage wilderness of wolves, savage crows, and killer bees and also a land filled with Indians (the winged monkeys) and Asian immigrants (the yellow Winkies). The South, the Quadlings, has both hammerhead hillbillies and dainty china people. The north, the Gillikins, has the hills and lakes that Baum associated with his vacation home in Michigan.

American politics as well as geography enter into The Wizard of Oz. In 1964 high school English teacher Henry Littlefield argued that Wizard of Oz was a satiric allegory of late 19th century populism. The idea enjoyed popularity for a while but then fell out of favor, in part because scholars started unearthing new facts about Baum’s political leanings. For instance, rather than a supporter of populism, he may have been a critic, which turns Littlefield’s interpretation on its head.

I’ve just read Quentin Taylor’s “Money and Politics in the Land of Oz,” however, which has convinced me that many of the populism parallels stand up, even though the overall idea needs tweaking.

Here’s the gist of the argument. Baum witnessed up close the Midwest’s drought and economic recession when he was a newspaperman in 1880s South Dakota and folded those conditions into his book. At the time, there was a major clash between East Coast banks, which wanted to return America to the gold standard, and Midwestern farmers, who were seeing their farms go under and hoped that they would be saved by moving to a bimetallic currency that included silver. (Gold and silver, incidentally, were weighed in ounces or oz.) Having silver in circulation would lead to some inflation, thereby raising the price of the farmers’ crops while effectively decreasing the cost of their fixed mortgages. At the height of the conflict, William Jennings Bryan captured the Democratic nomination for president with his legendary “thou shalt not crucify mankind on a cross of gold” speech.

As Littlefield and others have seen it, one finds the following equivalencies in the novel:

Dorothy – America’s innocence and can-do spirit

Yellow brick road – gold standard

Wicked Witch of the East – eastern banks

Silver slippers (changed to ruby in the movie) – silver coinage

Cyclone – Mary Lease, a firebreathing populist orator known as “the Kansas Cyclone” (Dorothy’s last name is “Gale”)

Toto – teetotalers, allied with the populists

Scarecrow – farmers

Tin Woodman – industrial workers

Cowardly Lion – William Jennings Bryan (get the rhyme?)

Giant spider killed by lion – corporate monoliths

Wicked Witch of the West – grim natural conditions

Wizard of Oz – Washington politicians

In this allegorical reading, if the electorate, operating out of Dorothy’s pioneer woman optimism, can march on Washington (like Coxey’s “Army” of the unemployed in 1894), free itself from the East Coast banks, and pressure slippery politicians to endorse bimetallism, the Midwest will be returned to prosperity. To do so, however, they must live up to their potential, which includes farmers using their brains, industrial workers discovering their hearts, and leaders displaying courage.

As Taylor notes, there are far too many correspondences to throw the theory out altogether. The problem lies in the heavy-handed way in which people have applied the symbols. Baum’s grandson declared such allegorizing to be “insane” given the fact that no one had picked up on it for 64 years. What good is an allegory if no one recognizes it as one?

It’s safe to say that The Wizard of Oz is not an allegory the way that Animal Farm or Gulliver’s Travels are allegories. Those works point to our own world to make their satiric points. Orwell meant for us to see how the descendants of Marx and Lenin had betrayed the ideas of the Russian Revolution. We are not reading too much into the work if we see Old Major as Marx/Lenin, Snowball as Trotsky (also some Lenin), and Napoleon as Stalin.

But I don’t think that Wizard of Oz is as innocent of allegorizing as, say, Tolkien claims Lord of the Rings to be. Tolkien insisted that his book should not be read as corresponding to current events, even though it is hard not to see the Shire as England, Tom Bombadil and Britain’s ancient Celtic roots, Sauron as Hitler, the Nazgul Black Riders as Nazi Storm Troopers, Saruman as Stalin, etc. I’m sympathetic with Tolkien’s point, however, because, unlike Orwell, he is creating a self-contained fantasy world. If it reflects the events of the time, it does so as all literature does. Tolkien doesn’t want us to see our world in Middle Earth. He wants to escape our world.

Taylor gives us a third way of looking at Wizard of Oz: it’s a children story that doubles as a private joke. In this joke, Baum is not promoting any particular cause but is having fun along the way. For instance, he’s neither for Bryan nor against him but having fun at his expense, including joking about his supposed cowardice for opposing American imperialism into the Philippines and (equating him now with the Wizard) seeing him as a Nebraska blowhard full of balloon-like hot air. The fantasy would win out over the satire, however, and Oz took on a life of its own in the numerous sequels.

Although few outside Ron and Rand Paul-type libertarians argue about gold and silver anymore, other themes from Baum’s time are alive and well today. It’s why Wizard of Oz has become like Cinderella or Snow White, an archetypal fairy tale capable of generating ever new versions. I’ll have more to say about Baum’s creation in future posts.

6 Trackbacks

[…] « Wizard of Oz, America’s Greatest Fairy Tale […]

[…] involves an effort of belief, and I have written about how L. Frank Baum, inspired by John Winthrop’s vision of a city on a hill and by Chicago […]

[…] As I’ve noted in the past, the light and dark strains are coin sides of the same grappling with reality: Baum wants to banish shadows from his fantasy while Poe makes his home in those repressed shadows. Baum represents the tradition that stretches from John Winthrop’s “city on the hill” to Walt Disney, and in his view the power of positive thinking allows us to create the reality we want. We have but to believe hard enough. Poe, on the other hand, looks at what we must ignore in order to believe that fantasy. In our political debates, I link those waving the flag of American exceptionalism with the Baum strain and those pointing out America’s sins with the Poe strain. […]

[…] Wizard of Oz, America’s Greatest Fairy Tale […]

[…] Wizard of Oz, America’s Greatest Fairy Tale […]

[…] Frank Baum was well acquainted with populist politicians and I have written about how both the Cowardly Lion and the Wizard may symbolize politicians of the 1890s while the Long […]