Wednesday

Until yesterday I’d never read John Milton’s Areopagitica, even though I was once a newspaper reporter and even though I have focused on censorship issues in my Theories of the Reader course. In addition to being a dazzling defense of the freedom to publish, Milton has a couple of nice observations about literature’s impact upon audiences.

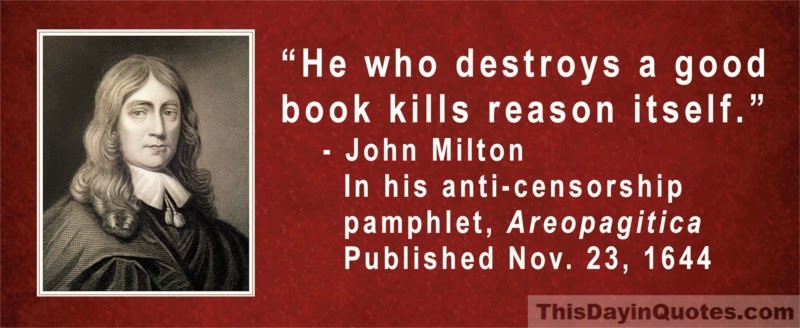

First of all, he has a great description of literature’s power. I’ve recently been writing about literature’s potential for ill as well as for good (here and here), and even though Milton acknowledges that books can do harm (he compares them to the dragon’s teeth sowed by Cadmus), he is still against censorship:

For Books are not absolutely dead things, but do contain a potency of life in them to be as active as that soul was whose progeny they are; nay they do preserve as in a viol the purest efficacy and extraction of that living intellect that bred them. I know they are as lively, and as vigorously productive, as those fabulous Dragons teeth; and being sown up and down, may chance to spring up armed men. And yet on the other hand, unless wariness be used, as good almost kill a Man as kill a good Book; who kills a Man kills a reasonable creature, God’s Image; but he who destroys a good Book, kills reason itself, kills the Image of God, as it were in the eye. Many a man lives a burden to the Earth; but a good Book is the precious life-blood of a master spirit, embalmed and treasured up on purpose to a life beyond life.

Arguing against Parliament’s passage of new licensing laws, Milton notes that the Spartans, while generally adverse to books, were nevertheless improved by their great lawgiver Lycurgus introducing Homer and Thales to them. In other words, look at what you’ll be missing if you follow your censoring impulses:

That other leading city of Greece, Lacedæmon, considering that Lycurgus their Law-giver was so addicted to elegant learning, as to have been the first that brought out of Ionia the scattered works of Homer, and sent the poet Thales from Crete to prepare and mollify the Spartan surliness with his smooth songs and odes, the better to plant among them law and civility, it is to be wondered how museless and unbookish they were, minding nought but the feats of war.

Rather than follow Plato’s lead in The Republic and protect citizens from bad examples (say, Homer’s misbehaving gods), Milton says that there are advantages to be gained even from reading objectionable passages. For instance, we cannot know what virtue is until we see it contrasted with vice.

Furthermore, Milron believes that vice has been put before us to test us. He draws an example from Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene to make his point. In Book II Guyon enters the Cave of Mammon but resists temptation:

He that can apprehend and consider vice with all her baits and seeming pleasures, and yet abstain, and yet distinguish, and yet prefer that which is truly better, he is the true wayfaring Christian. I cannot praise a fugitive and cloistered virtue, unexercised and unbreathed, that never sallies out and sees her adversary, but slinks out of the race, where that immortal garland is to be run for, not without dust and heat. Assuredly we bring not innocence into the world, we bring impurity much rather: that which purifies us is trial, and trial is by what is contrary. That virtue therefore which is but a youngling in the contemplation of evil, and knows not the utmost that vice promises to her followers, and rejects it, is but a blank virtue, not a pure; her whiteness is but an excremental whiteness; Which was the reason why our sage and serious Poet Spenser, whom I dare be known to think a better teacher then Scotus or Aquinas, describing true temperance under the person of Guyon, brings him in with his palmer through the cave of Mammon, and the bower of earthly bliss that he might see and know, and yet abstain.

To give you a taste of the trials that Guyon encounters, here’s what he sees in Mammon’s cave:

And round about him lay on euery side

Great heapes of gold, that neuer could be spent:

Of which some were rude owre, not purifide

Of Mulcibers deuouring element;

Some others were new driuen, and distent

Into great Ingoes, and to wedges square;

Some in round plates withouten moniment;

But most were stampt, and in their metall bare

The antique shapes of kings and kesars straunge & rare.

Better to wrestle with temptation first in a book, Milton goes on to say, so that we can safely scout “the regions of sin and falsity”:

Since therefore the knowledge and survey of vice is in this world so necessary to the constituting of human virtue, and the scanning of error to the confirmation of truth, how can we more safely, and with less danger scout into the regions of sin and falsity then by reading all manner of tracts, and hearing all manner of reason? And this is the benefit which may be had of books promiscuously read.

Milton goes on to make elaborate arguments, some practical, some spiritual, for the free circulation of printed material. It’s a rather amazing document to be found in the 17th century.